Did you know that California has a thoroughly Catholic history? Perhaps the most Catholic history of any state in the Union?

It’s true. It was literally founded by Franciscan friars and most of its major cities either began as Catholic missions or at least bear Catholic names: Sacramento ([The Blessed] Sacrament), Los Angeles ([Our Lady of] the Angels), San Jose (St. Joseph), San Diego (named for Saint Diego de Alcalá)…the list goes on and on and on.

For those who love to explore the profound Catholic heritage of the United States, it’s a must-visit.

Does this surprise you? After all, California is hardly known for being a bastion of religious practice or traditional values (though there is plenty to be had in all regions of California if you know where to look).

In fact, modern California presents a rather stunning dichotomy between the Catholic mission it was born to be and the less-than-Catholic public policies it is famous for. It seems strangely destined for an a-religious future, but it has an enduring religious past that it cannot rewrite.

I happen to love visiting California. It is one of the most beautiful and geographically diverse states in the Union. It’s your playground whether you’re a surfer, mountain-climber, desert wanderer, or whatever—and being the roadtrip-lover that I am, it’s an amazing place to hit the road. Highway 1, which I traversed from Malibu to Monterey a few years back, is every bit as stunning as legend says.

I therefore needed little persuasion to make the cross-country flight to attend the wedding of Good Catholic’s own Genevieve Netherton in San Diego in November. But it wasn’t just a vacation to me—it was a “golden” opportunity to investigate the Catholic past and present of this beautiful yet utterly self-contradictory piece of American territory.

So let’s go find the real California. Let’s dive beneath the surface and find her true identity—a thoroughly Catholic heart carved out by the prayer and sacrifice of generations of missionaries and dedicated faithful.

Mission-Driven

The Franciscans first came to the Spanish region of Alta California in 1769, when a five-foot-two friar by the name of Junípero Serra—a twenty-year veteran of the missions in Mexico—volunteered to join a Spanish expedition to establish presidios (forts) and missions in the area. The first mission, San Diego, founded that same year, was the starting point of what is now one of California’s largest and most popular cities.

The “Apostle of California” gave his life for the conversion of this future state, walking thousands of miles all across the territory to spread the Faith and attend to the missions and the Native Americans they served—and to defend the rights of both from the frequent encroachments of the local military authorities. He would go on to found eight more missions, including another of California’s most recognizable names: San Francisco, named for St. Francis of Assisi.

All in all, between 1769 and 1823, the Franciscans founded twenty-one missions that form a chain from one end of the state to the other. Pilgrims can traverse the whole route via the California Mission Trail, a hiking path that winds all the way from San Diego to the wine country of Sonoma.

That means the backbone of this state is literally a string of historic Catholic communities—many of them still active Mass centers, by the way—with their origins in the life of a saint.

I couldn’t walk the whole trail during the one long weekend I was on the West Coast last November. That’s a job for another trip. But I did make time to visit the three missions that were within driving distance of my home base in Valley Center: San Diego, San Luis Rey, and the famous San Juan Capistrano.

Jewel of the California Missions

The very name San Juan Capistrano rolls off the tongue like music. Probably no other mission evokes the image of old-time, trading-post, frontier California quite like this place. It was known as the most beautiful and important mission of them all, still bearing the title “Jewel of the California Missions.”

Situated about halfway between San Diego and Los Angeles, the mission is right in the center of the little town that grew up around it and took its name. For some reason the bustling location surprised me—I think I was expecting a historic site way out in the desert wilderness somewhere, and I suppose at the time of its founding, it was.

St. Junípero Serra founded San Juan Capistrano in 1776, the 7th of the 21 missions. It contains the last chapel standing in which the saint himself said Mass—and that structure, known as the Serra Chapel and constructed in 1782, also happens to be the oldest standing building in the state.

Poor California. To erase your Catholic history, you’d have to erase yourself.

Fortunately for both the missions and California, there seems to be no shortage of dedicated people and organizations that support and maintain the missions, and no one seems to be calling for their erasure. I’m guessing that not all these folk are people of religious belief or fervor—many of them are probably just lovers of history, and native Californians who consider these institutions as vital pieces of their state’s past.

Even Junípero Serra himself seems to have withstood the occasional tempest that has blown his way. Statues of him have been removed from the state capitol and elsewhere in the state—moves motivated by a storm of politics, misplaced rage, and profound ignorance of how the missions actually worked (and how the Natives themselves actually felt about it all).

But here at San Juan Capistrano, the memory of this giant of a saint lives on, although the statue of him has been moved inside to preclude any attempts at vandalism.

Here, in this place that was once a refuge from hostile forces and nurtured the seedlings of faith, you can rest for a minute or two while the storms of destruction pass by outside.

Fertile Ground

Hardy desert cacti grew tall beside the rugged adobe walls that were separated from the street by a narrow sidewalk leading me to the main entrance of the mission.

Within, I was met by a courtyard full of native plants, including delightful orange trees heavy with fruit not yet ripe for the picking (they ripen in the winter). Roses of various shades formed a fine garden of their own, and a vibrant magenta flowerbush of unknown identity found a happy home near the mission bells.

The desert seems, strangely enough, the perfect place for the most wild, colorful, and delicious plants to grow—and, it seems, for the seeds of faith to take root.

Wine grapes, too, are grown here. The criolla—the “mission grape”—was first cultivated here in 1779. In fact, this mission might well have produced the first wine in Alta California, which now, especially in its famed Napa Valley region, is the top producer of wine in the USA.

Really, California, where would you be without this place?

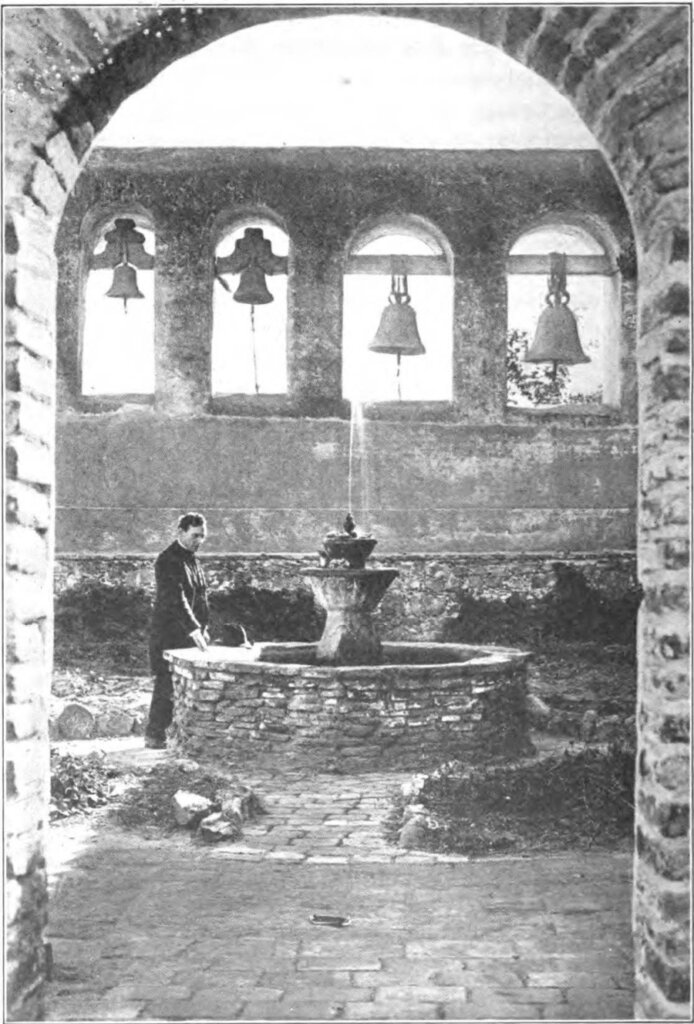

The Bells of San Juan

One of the most iconic features of the mission—of any mission, really—is the bells.

There are four of them at San Juan Capistrano, hanging high and proud in a great brick wall near the Serra Chapel. As is the charming tradition with church bells, they all have names: San Vicente, San Juan, San Antonio, and San Rafael. On each is inscribed in Latin:

- “Praised be Jesus, San Vicente. In honor of the Reverend Fathers, Ministers Fray Vicente Fustér, and Fray Juan Santiago, 1796.”

- “Hail Mary most pure. Ruelas made me, and I am called San Juan, 1796.”

- “Hail Mary most pure, San Antonio, 1804.”

- “Hail Mary most pure, San Rafael, 1804.”

Another immediately noticeable feature of San Juan Capistrano is a giant, raggy, cracked-open, cavern-like structure that rises on the other end of the bell wall from the Serra Chapel.

This is all that remains of the sanctuary of the “Great Stone Church”— a magnificent structure built in 1806 to house the growing number of faithful but which tragically collapsed in an earthquake only six years later. Forty-two Native Catholics died that day; they are buried on the mission grounds and commemorated by a plaque nearby.

San Vicente and San Juan suffered cracks during this earthquake. In 2000, to celebrate Pope St. John Paul II raising the mission to the status of minor basilica, the damaged bells were recast, just like they were before. The original bells were moved to another prominent spot (where the bell tower of the Great Stone Church once stood) and the new ones were hung in the bell wall.

Today, the bells ring seven times each morning in honor of St. Junípero Serra, and on other important feast days and holidays as well.

Under the watchful gaze of the bells I milled about the lovely grounds, passing in and out of the various buildings, the glorious Serra Chapel, the thriving gardens, and the preserved remnants of a bygone age of faith. Among the artifacts is the oldest iron forge of its kind in the state.

Losing San Juan—and Getting It Back Again

The mission thrived for many years after its founding. But as is the way of temporal things—even those with a spiritual mission—they never seem to last.

Due to various factors the mission faced a steady decline, beginning in the 1820s.

Among its misfortunes were the seismic shifts in the political landscape of Alta California during that era.

Mexico revolted against Spain and gained its independence in 1821, which meant that Alta California was now part of an independent Mexico. I am not an expert, or even a student, in the complex history of Mexico’s revolution(s), but I think it’s accurate to say that things just got more and more secular and anti-religious as time wore on.

Already on the decline, San Juan suffered further when, in 1833, the Mexican government secularized the California missions—that is, deprived them of their status as religious entities. The Franciscans and the resident Indians—their numbers already dwindling—continued to depart, and by 1845, the mission was in the hands of private landowners.

The missions and its once-beautiful grounds fell into decay. But the story of San Juan Capistrano was not finished.

In 1850, California was admitted into the United States of America as its 31st member. The Bishop of Monterey (California’s only diocese at the time), Bishop Joseph Alemany, petitioned the U.S. government for the return of the missions to the Church. None other than President Abraham Lincoln granted his request and restored the Church’s property in 1865.

San Juan Capistrano was back in the right hands, but would not see sustained revitalization until the early 20th century, with the arrival of the “Great Restorer” of San Juan: Fr. St. John O’Sullivan.

St. John of San Juan

Fr. O’Sullivan’s name really was St. John, pronounced just as you see it—although some people, uncomfortable with calling a living person “Saint,” pronounced “Saint John” as “Sin-Jin.” I think I would have been okay with calling him St. John if I’d lived back then—after all, he certainly was a saint to the failing mission of San Juan Capistrano.

Ordained in 1904 at the age of thirty for his home diocese of Louisville, Kentucky, Fr. O’Sullivan received the unhappy diagnosis of tuberculosis not long afterward—devastating news for a newly-ordained cleric. He was not expected to live long.

But God’s providence always brings glorious things out of our suffering. If Fr. O’Sullivan hadn’t been so ill, he never would have come to San Juan Capistrano, and if he hadn’t come to San Juan Capistrano, who knows what would have happened to this place.

Here’s what did happen.

Fr. O’Sullivan made the trek to the southwest in 1910 in the hopes that the clement, dry weather would improve his health. A priest-friend in Arizona suggested San Juan Capistrano as a good post for him, and Fr. O’Sullivan decided to check it out.

It was love at first sight.

Many would have seen only a dilapidated mess that would require untold amounts of money and work to even begin to restore. But Fr. O’Sullivan saw his life’s calling.

Over the twenty-three years he was in charge of the mission, Fr. O’Sullivan led a massive restoration effort, though he had to live in a tent to begin with since the living quarters were uninhabitable. Utterly defying his illness, he worked and worked and worked to bring this seemingly-dead place back to life.

He used historically-correct materials as much as possible, desiring to restore the sacred site back to its original splendor, as it was in the glory days of the missions.

He focused particular efforts on the Serra Chapel, re-establishing its failing integrity and outfitting it with a magnificent centuries-old gilded retablo (reredos) from Spain. The Bishop of Los Angeles actually donated this piece, as it was originally intended for the cathedral there but hadn’t been needed.

And the tuberculosis? It’s really only a footnote in Fr. O’Sullivan’s life.

His health did improve as he labored tirelessly at San Juan. He lived to the relatively ripe age of 59, leaving an irreplaceable legacy behind him when he died in 1933.

He was the first resident priest at San Juan Capistrano since 1886, and the first pastor of modern times. The place has been a functional parish and thriving historical site ever since.

If you ever visit San Juan, you can visit the grave of this remarkable priest, who is buried on the grounds of the mission he loved so much.

When the Swallows Come Back to Capistrano

Of course, you can’t talk about San Juan Capistrano without talking about some of its most famous residents: the ever-returning cliff swallows.

In perfect accord with popular belief and popular song, the swallows really do come back to Capistrano every year after their winter sojourn in Argentina. They build their little mud huts on the archways of the mission buildings, raising their feathered families each spring and delighting visitors with their mirthful presence until they head south in the fall.

A hiatus occurred in the birds’ regular presence in the mid-2000s, as taller buildings sprang up in the area and attracted them away from the mission. But successful plans to coax the swallows back were implemented, and they have returned to their happy mission home.

They remain, in addition to the bells, the most enduring symbol of Mission San Juan Capistrano.

While it’s impossible to say when swallows first began nesting at the 250-year-old mission, their presence in modern times has a fascinating connection to Fr. St. John O’Sullivan’s tenure.

In the book Capistrano Nights, Fr. O’Sullivan relates that he was walking along a street in town and saw a shopkeeper knocking the swallows’ mud nests off the eaves of his shop. When the priest asked what he was doing, the shopkeeper said he was ridding his shop of those “dirty birds.”

Fr. O’Sullivan then said: “Come on swallows, I’ll give you shelter. Come to the Mission. There’s room enough there for all.”

The very next day, the good priest found the swallows building nests at the Mission!

Fr. O’Sullivan noted that the swallows returned from South America right around St. Joseph’s Day—March 19th. He instituted a festival to celebrate the saint’s feast day and the birds’ return, a festival that is still held every year at San Juan and coincides with other events held in the town to welcome the beloved birds.

Quo Vadis, California?

Years ago I was driving from Wickenburg, Arizona to Los Angeles. It was a magnificent route on Highway 10 through the Colorado Desert, the landscape adorned with cinnamon mountains, endless sandscapes, and the frequent golden eagle sitting atop a telephone wire. It would have been desolation warmed up to some; but to me and my pickup truck, it was heaven.

I remember driving through a particularly long, abandoned, civilization-less valley a few hours into my drive. My gas tank was getting low, but a station was slow to appear. Painfully slow.

As my nerves were building, I at last spied a refueling point and pulled off. I’m guessing that particular gas station can charge whatever it wants because it’s rather secure in its position as the last hope of desperate desert-crossers like myself. I don’t remember how much it was per gallon, and I certainly didn’t care.

I also didn’t know where exactly I was at the time, so I was surprised to see a museum dedicated to General George Patton adjacent to the gas station. Seemed like a very odd spot for such a monument, but then again, I was unaware that I was standing at the entrance to the historic Camp Young, a World War II era Army base that served as headquarters for a massive training center for desert warfare. Patton was the first commander of the center.

But what fascinated me even more than the seemingly out-of-place museum was a simple sign I saw posted on a door. I don’t remember where the door was—maybe into the museum, maybe into the nearby cafe where I stopped to get some fuel for myself, or maybe into a passageway between the two.

I’ll never forget what that sign said, though. It was something to the effect of:

“Sunday Mass will be held in such-and-such a place rather than the usual such-and-such chapel.”

Sunday Mass? Here? In the middle of absolutely nowhere? Who goes to Mass out here?

Well, someone does. Deep in the sands of the most abandoned corner of California, faith of some kind survives. It was a small but deeply impressive testament to the pervasive and enduring Catholicity of this state.

For the Franciscan padres who gave up their lives to make the waters of faith flow from the dry rocks of Alta California, the fruits of their labors must have been so often hidden from their eyes. They not only labored to plant the faith in the hearts of the native souls under their care, but also battled successions of local governments who often took little interest in evangelization and sometimes were outright hostile to it.

And their work did bear fruit, fruit that proved to be lasting.

“You did not choose me, but I chose you and appointed you that you should go and bear fruit and that your fruit should abide…”

John 15:16

Despite challenges, the Faith thrived here and spread its roots so thoroughly that it’s now near-impossible to rip it out, or run from it, or pretend it doesn’t exist—whether you flee to the cities, the coast, the mountains, or the wild, waterless desert.

As it says in the Psalm that those padres surely knew well:

Whither shall I go from thy Spirit?

Or whither shall I flee from thy presence?

If I ascend to heaven, thou art there!

If I make my bed in Sheol, thou art there!

If I take the wings of the morning

and dwell in the uttermost parts of the sea,

even there thy hand shall lead me,

and thy right hand shall hold me.

Psalm 139:7-10

As I left San Juan Capistrano and continued my November journey, I would meet other bastions of faith growing out of the thirsty ground of California—among them St. Michael’s Abbey, home to a vibrant community of the Norbertine Order and a flourishing center of monastic life, liturgy, and sacred art.

My visit to St. Michael’s will comprise our next stop as we journey on the trail of Catholic California, so stay tuned. +