“Find its mother.”

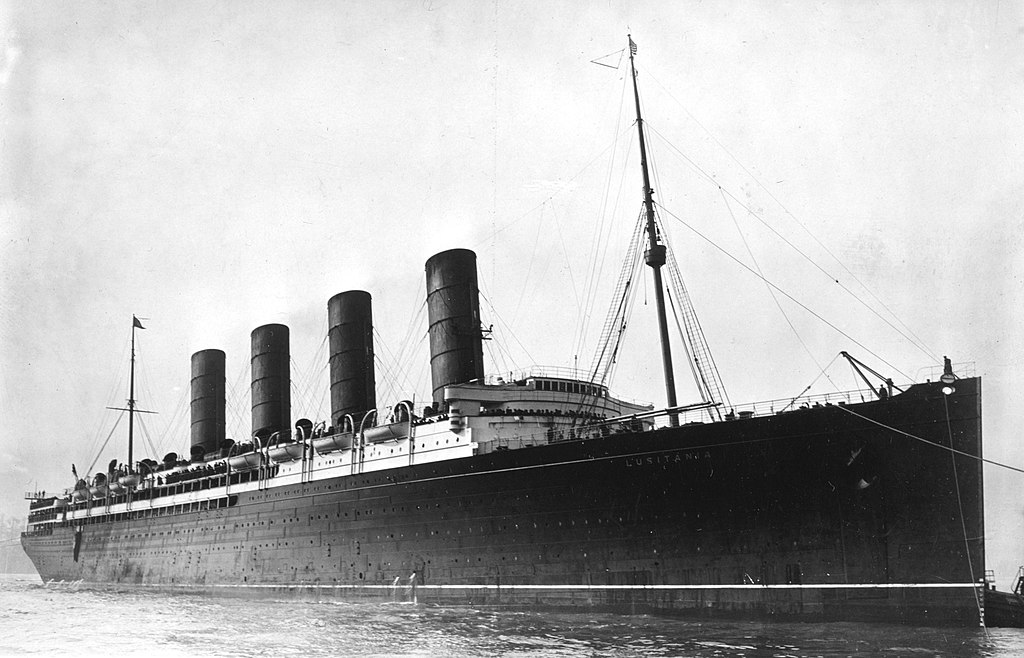

These words were some of the last spoken by Fr. Basil William Maturin as he handed a child down to a lifeboat from the sinking Lusitania. The ship had been hit by a torpedo on May 7th, 1915.

Just moments before rescuing the child, Fr. Maturin had been seen administering the Last Rites to several passengers amidst the chaotic terror and confusion of the doomed ship. A survivor described him as “pale, but calm” during the horrible sinking of Cunard’s RMS Lusitania.

When his body washed ashore a few days later, it would prove what one survivor had conjectured: Fr. Maturin sought neither a life boat nor a life vest for himself, as he knew there were not enough to go around.

Records indicate that there was one other priest on board the Lusitania that day. He died in a lifeboat with a life vest on.

Some 1,197 passengers perished, and 618 were never found. Maturin’s body, #223, was recovered by two elderly fisherman in Ballycotton Bay in Ireland and was returned to England.

Having once predicted that his funeral would be held in a half-empty church on a rainy day, Fr. Maturin would instead have “impressive last rites” with crowds of people attending at Westminster Cathedral:

Father Maturin used to say [writes Mrs. Wilfrid Ward] that he knew he should have a lonely funeral, and he prophesied that it would be on a wet day and in an empty church! This came back to us when the body was brought home, and the great cathedral at Westminster was crowded for the Requiem. He had a larger place in the heart of Catholic London than he ever himself suspected.

Father Maturin: A Memoire by Masie Ward

Although Warned, Passengers Still Embarked on the Fateful Journey

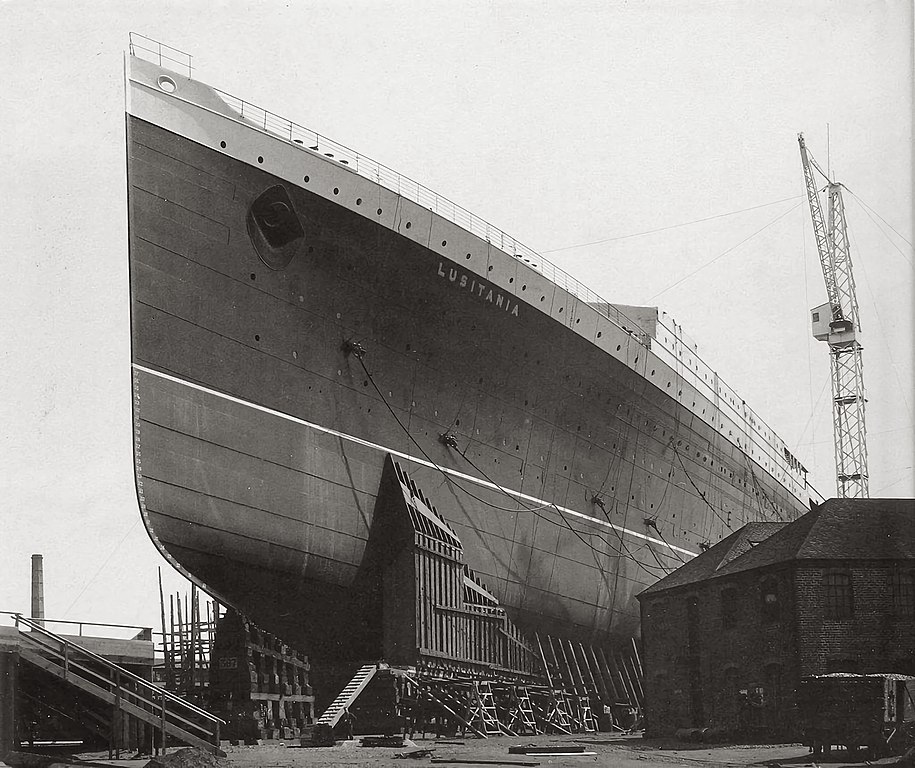

The Lusitania departed from New York City’s Pier 54 amidst numerous warnings that it would be sailing into a war zone.

In the days before the ship was to set sail, various warnings were issued, yet records show that only one passenger’s reserved ticket was canceled. Although there was much discussion on board about the war and German submarine activity, as Anthony Richards notes in Lusitania Sinking, “There was a widespread refusal to believe that anything untoward could happen to the ship.”

All the passengers were instructed in the use of life jackets and lifeboats and were prohibited from displaying any light, such as matches, on deck. They were also told to cover portholes.

Although many believed that nothing could happen to the huge ocean liner, the Lusitania sank in less than eighteen minutes after it was struck by a torpedo from a German U-boat on May 7th, 1915, at 2:10 in the afternoon.

Fr. Maturin’s Spiritual Fortitude

A calm, intentional spirit enabled Fr. Maturin to direct the last moments of his life to tending to others. Was that spirit born out of a sudden courageous disposition? We cannot know for sure, but it’s unlikely. There were clues in his life and in his writings indicating a man who had dedicated himself to seeking God’s will and in which we can recognize a consistent theme of humility and trust in the friendship of God.

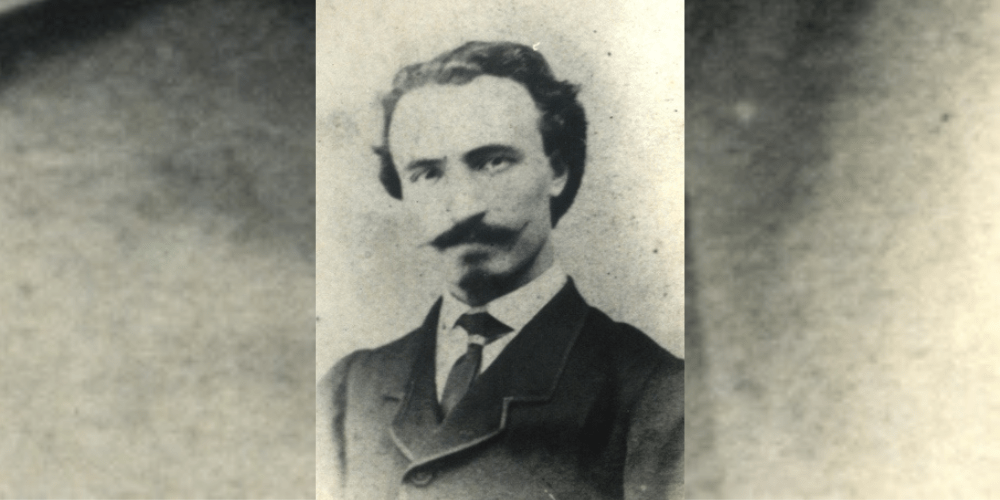

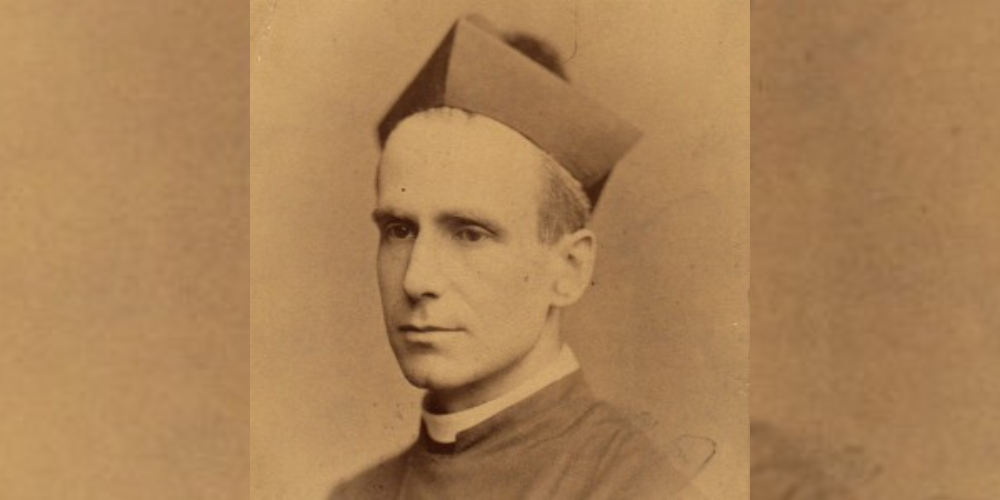

Basil William Maturin was born on February 15th, 1847 at All Saints’ Vicarage, in Grangegorman, Dublin. He was the third ten children born to Anglican clergyman Rev. William Maturin and his wife, Jane Cooke. His grandfather was a notable writer of the time, Charles Robert Maturin.

Religion was a strong influence in the Maturin children’s lives. When he was a young man, Basil assisted in training the choir and playing the organ at his father’s Anglican church. Educated at home and later at a Dublin day school, he went on to attend Trinity College in Dublin, where he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in 1870.

Initially intending on making a career in the army as an engineer, his outlook on life changed after suffering a severe attack of scarlet fever in 1868, the same year his brother Arthur died. These experiences altered Maturin’s choice for a vocation and he decided to become a clergyman. Ordained a deacon in the Anglican Church in 1870, Fr. Maturin went to England as a curate, to Peterstow, Herefordshire, where his father’s friend Dr. John Jebb was rector.

Soon after that he joined the Society of St. John the Evangelist and entered the novitiate at Cowley, Oxford, in February 1873. As a Cowley Father, he was sent in 1876 to establish a mission in Philadelphia, where he worked as an assistant priest, and in 1881 became rector of St Clement’s Episcopal Church there.

Father Maturin Becomes a Roman Catholic

Though he proved to be an effective and popular preacher, Fr. Maturin began to have growing doubts about his own faith and started to question aspects of Protestantism. There had already developed in Fr. Maturin’s mind an increased interest in Catholicism.

He returned to Oxford in 1888 but in at attempt at soul-searching, he took a six-month visit in 1889 to a mission center in Cape Town, South Africa. Returning again to Britain, he began conducting retreats on the spiritual life. In 1896 he produced the first in a series of religious publications, Some Principles and Practices of Spiritual Life.

In 1889, Maturin was assigned a mission at Mount Calvary Church in Baltimore, Maryland. There, his superior told him that he was acting like a Catholic and the mission was accused of “Romish practices.”

His continuing religious anxieties eventually led to his conversion to Catholicism.

Father Maturin arranged to go to Beaumont College on the twenty-fourth anniversary of his going to Cowley, February 22, 1897, and he was there received into the Church on March 5.

Father Maturin: A Memoire, by Masie Ward

The journey to the Catholic Church was not an easy one for Fr. Maturin, as many of his letters reveal. At times he felt “tortured” by the thought of what the transition would mean.

Yet he describes an unceasing beckoning that would finally draw him to what he would affectionately call “his home”:

Then you began to realise more and more that you were an alien, the citizen of another country, a waif adopted by one who was not his mother, and all the inborn instincts for home and country had awakened in you. The Voice of the Teacher you had been following moved you, and drew you, because of its resemblance to that of another whom your instincts recognised almost unconsciously. All that was true and beautiful in what she taught you, stirred and awakened dim memories of a long-forgotten home.

In a word, you perceived that in truth you had never been an Anglican, that what you had loved and craved for was the Roman Catholic Church, and that you had loved and received all, and only, that which resembled her.

Father Maturin: A Memoire, by Masie Ward

It was with this zeal that Fr. Maturin began his new life as a Catholic.

He never forgot where he came from, however, and always spoke highly of his childhood, adolescence, and even adult years as an Anglican. To a fellow Anglican clergy member who was struggling as he considered the Catholic Church himself, he wrote:

I believe it all to be the most healthy and proper state of mind for any one who loves and has loved their religion in the past. You have believed in, and been associated with, all that is best and most beautiful in the English Church…and most of what they teach is true; but you will find in the Roman Church, in time, something more beautiful, more tender and more human, as well as divine, and something so much broader and larger, that you can only understand it by experiencing it.

Father Maturin: A Memoire, by Masie Ward

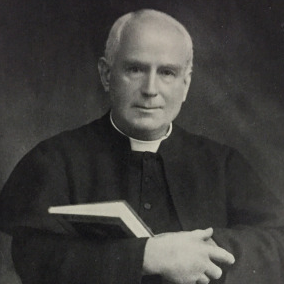

Fr. Maturin moved to Rome where he studied theology at the Canadian College (Rome) and was ordained a Catholic priest in 1898 by his friend Archbishop Herbert Cardinal Vaughan.

Following his return to England he lived initially at Archbishop’s House, Westminster, and with a love of service, focused on missionary work and then served at St Mary’s, Cadogan Street, in 1901. He became the parish priest of Pimlico near central Londan and, in 1905, having joined the newly established Society of Westminster Diocesan Missionaries, organized the opening of St Margaret’s Chapel on St Leonard’s Street, where huge crowds came to hear his sermons.

He continued to write, publishing Self-knowledge and Self-Discipline in 1905 (still popular under its republished name, Christian Self-Mastery, Laws of the Spiritual Life in 1907, and his autobiographical The Price of Unity (1912), in which he traced his gradual move towards the Catholic Church.

In writing about his own conversion and about the Church of England from which he came, Fr. Maturin explained in The Price of Unity:

“Does it not look as if Divine Providence were constantly calling attention to the Nemesis that has followed upon this assertion of independence? ‘Look’, it seems to say, ‘at the result. It is Rome or chaos. What you tried to put in her place won’t work. The Church needs a divinely constituted authority at her head. To secure a unity in doctrine and discipline, the Episcopate must be under an authority that can keep it in order, and at one with itself, and this can be nothing else but an authority that it knows to have been constituted by our Lord Himself. The theory of an independent Episcopate has been tried and found wanting.'”

The Price of Unity

As an Anglican priest, Fr. Maturin had been known for his sermons, and as a Catholic priest his reputation for preaching continued. Those who heard him speak told of how he had a “beautiful way with words” and could take something universal and make a person feel as if he were speaking to him or her directly :

Apart from himself, as distinct from his lovable self and his great personality, who can forget the wonderful preaching power of Father Maturin. It was so distinctive, so unlike anything that one heard from anyone else – it was so original. Full of information and instruction, it held his hearers spellbound; it took possession of them soul and mind, and made it impossible to be inattentive. It was true eloquence a torrent of eloquence – but it was more; it had a fascination that was irresistible.

Father Maturin: A Memoire, by Masie Ward

Fr. Maturin Taught That We Must See Ourselves As We Really Are

In addition to his preaching, Fr. Maturin was known for his skill in the confessional. According to some who knew him “he had a great gift for leading souls” (Catholic Exchange).

Yet at times in his own spiritual life, Fr. Maturin seemed to have felt that his life and vocation lacked real purpose. He occasionally was thought to suffer from depression. Perhaps it was some of these very reasons that caused him to seek a greater knowledge of God—as it says in Christian Self-Mastery, “in order to see ourselves at all we must do so in light of who God is.”

He wrote often about the human condition and spoke about the need for an honest view of oneself.

Fr. Maturin wrote:

“One may have a very deep knowledge of human character in general, and yet be profoundly ignorant of one’s own character. We look with the same eyes, yet the eyes that pierce so easily through the artifices and deceptions of others become clouded and the vision disturbed when they turn inwards and examine oneself.”

Christian Self-Mastery

Fr. Maturin returned to Ireland on several occasions, and frequently preached at the Carmelite Church, Clarendon Street, in Dublin.

In 1910 at the age of sixty-three, he attempted to enter the monastic life at Downside, a Benedictine monastery in Ireland, but proved unsuccessful.

In 1912 Maturin came to Downside and was clothed as a monk by Abbot Cuthbert Butler in the Abbey Church. Unfortunately, after just a few months he resigned the habit, instead choosing to become a secular priest, and in 1913 he was made Chaplain to the University of Oxford.

Downside Abbey Archives and Library

He returned to London and began working in St James’s, Spanish Place, while maintaining his preaching commitments.

It was shortly after this that Fr. Maturin accepted the post of Catholic Chaplain to Oxford University in 1913.

Although he was worried at first about residing and working at Oxford because of his past there as an Anglican, he came to love the work with students and it appears that they loved him back:

Oxford was a place that called urgently for a man of Father Maturin’s outlook and abilities, and to which he was ideally fitted. A Catholic undergraduate exclaimed with joy: ‘What a comfort it is to have a chaplain to whom I can introduce my agnostic friends.’

Though not without the incidental fits of depression that had haunted him all his life, Father Maturin was exceedingly happy at Oxford during the short time that remained. He loved the undergraduates both the Catholics and their various friends and they loved him.

Father Maturin: A Memoire, by Masie Ward

As a chaplain he continued to give retreats and talks and often would travel, sometimes out of the country, to do so.

It was in this capacity that Maturin boarded Cunard’s RMS Lusitania in May 1915, after a successful preaching tour in several American cities. He had just finished a Lenten series at the Church of Our Lady of Lourdes in New York when he was returning to England on the fateful ship.

A Life Ended As It Had Been Lived…In the Service of God

None of us knows the day or the hour which will come to be our last.

We are told by the saints to think often of our death not only to prepare ourselves for that inevitable day, but also to remember to store up heavenly treasures and not earthly ones.

Fr. Basil William Maturin could not have predicted that he would be heading for his death as he boarded the Lusitania in the spring of 1915, but perhaps the actions of his final moments on this earth might have been more predictable to others than to himself. This is because true humility is known in a higher sense as that by which a man has a modest estimate of his own worth and submits himself to others.

In particular, Fr. Maturin wrote about the need for human beings to know themselves so that they might see themselves in light of God who created them and “in that light come to rest in the goodness of God’s Holy Will.” This remains in essence a necessity of the spiritual life, as it was taught by Christ himself: “Learn of me, because I am meek, and humble of heart: and you shall find rest to your souls” (Matthew 11:29).

In one of his books, Maturin explained how we grow in humility when we finally understand that without God we are nothing:

…The more we grow in the knowledge of God the deeper our knowledge of self, and if we would attain to any knowledge of God there must be some knowledge of self.

So may we persevere, in such ways as we have been considering, or in any of those manifold ways in which God is wont to teach those who are in earnest, determined that we will not rest till we have penetrated through the many chambers and corridors, thronged with those strange forms that huny hither and thither bringing news from without or carrying out orders from within, filling all with the noise and tumult of their activity, till we have forced our way through all this and entered into the presence chamber and lifted the veil and seen ourselves face to face.

Christian Self-Mastery

May we, like Fr. Maturin, seek to know ourselves—not so that we will become self-focused, but that in seeing ourselves, we will understand in more profound and deep ways our utter dependence on God.