It was the most beautiful garden you’ve ever seen.

As I sat in that garden in York, England, sipping coffee brewed in a beautiful ceramic French press and talking to Fr. Daniel Seward of the Oratorian Fathers, it was impossible not to notice the glorious growing things all around us.

I was told it was the work of one Father Stephen, who—judging by the fruits of his work—must have more than a green thumb: he must have a thumb of emerald.

Perhaps the most stunning part about it was the fact that we were not exactly out in the country. I would call the ancient establishment of York—with its majestic medieval-upon-Roman city walls—more of a town than a city. Even so, 11 High Petergate—the home of the Oratorians there—was right in the middle of a busy market street, hardly somewhere you’d expect to find flowers growing so well.

The “secret garden,” as you might call it, greets you as you walk out the back door of the Oratorian house. A perfectly manicured, perfectly flat green lawn hosted the table and chairs where Father and I sat for our conversation. Roses (that ever-present resident of every English garden of every rank and station) and other perennials formed a wreath of color and life along the encircling walls.

Above us towered St. Wilfred’s, the beautiful old church that was the center of operations for the York Oratorians. A little further away, on the other side, was Yorkminster, the now-Anglican cathedral, whose majestic towers are a symbol of York and a constant draw for visitors.

Good Advice

I didn’t get around to going to Yorkminster that day. In fact, I wasn’t originally planning on going to York at all.

Providentially, I hadn’t booked up my schedule before arriving in England, and was able to act on the good advice of my friends at St. Mary’s in Warrington when one of them said with a knowing smile, “You should go to York.”

The Fathers of the Oratory graciously accommodated my last-minute request for an interview, which is how I found myself in that garden on that day talking to Fr. Daniel at 9 AM after getting off the 1 hr 40 minute train from Warrington.

That was the starting point of a day that would solidify York as one of my favorite places on the island of Great Britain.

The York Oratory

About ten years ago, the Bishop of Middlesbrough invited Oratorians from the Oxford Oratory to found a new house in his diocese. A suitable location was found in York, and the house was officially established as its own entity in 2019, the youngest house of Oratorians in the world.

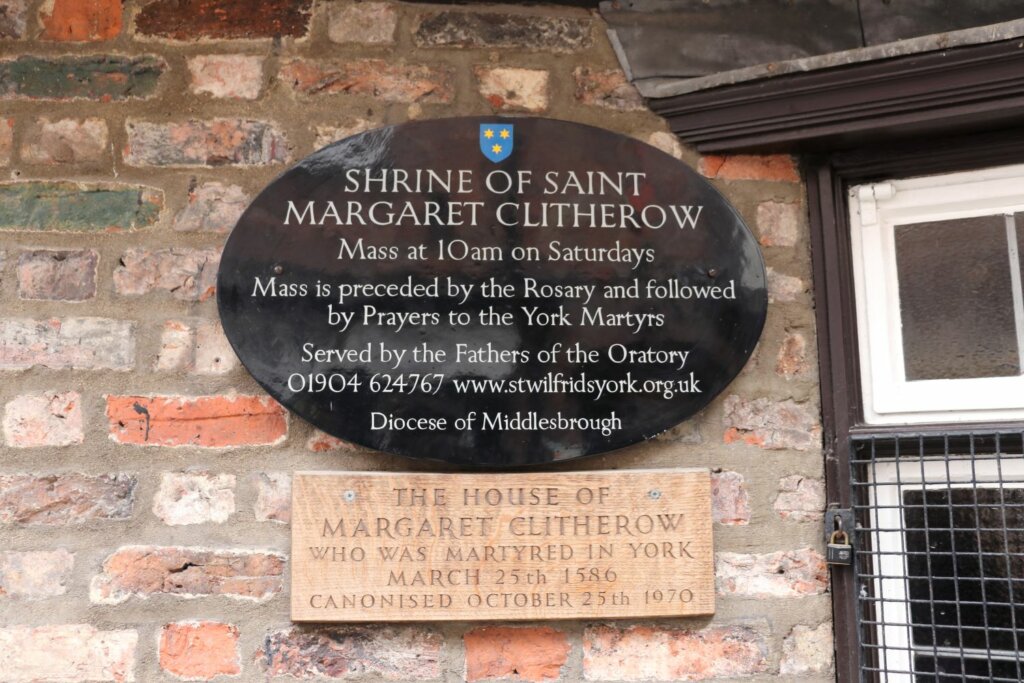

The Fathers here serve the aforementioned St. Wilfrid’s parish as well as St. Joseph’s, a parish a couple miles away in a suburb of the city. They also celebrate Mass at the shrine of St. Margaret Clitherow, which I would visit later that day, and run the chaplaincy of the University of York.

Their house, adjacent to St. Wilfrid’s, is right down the road from Yorkminster on a main thoroughfare through the city. It would be easy to miss, so well did the front door blend in with the shopfronts on either side.

It might be a bit too much hustle and bustle for some, but this is exactly where the Oratorians like to grow their gardens. If you recall from our first encounter with their way of life in Dublin, Oratories are always in cities, in central locations where they can serve people—working people, students, etc.—right where they spend most of their time.

“It’s an ideal location, couldn’t be more central,” Fr. Daniel explained. “It’s a place where we’re very visible, people pass the front door of the church, they come in. That sort of city center ‘ministry of presence’ is really what we do: having an open church, hearing confessions every day, having the liturgy solemnly celebrated, that’s sort of the essence of our vocation.”

Fishing with a Line, Not with a Net

Re-listening to the recording of my conversation with Fr. Daniel was rather irritating. I talked too much and brought too many of my own ideas. But the soft-spoken priest was patient as he answered my questions—and redirected my expected answers down slightly different paths than I was, perhaps, anticipating.

I asked about the response of the people to the ministry of the Oratorians, saying something about numbers of parishioners (I guess I hadn’t learned quite yet that numbers aren’t really very interesting or important).

While he affirmed a healthy contingent of regulars, he also said:

“More important than the raw numbers, actually, are the fact that we have established or are establishing a community of people who are very committed, and who really make this place their life. It’s where they meet their friends, it’s where they socialize, therefore it’s a kind of springboard for inviting people to holiness.”

Of course, the starting point of any such community is the liturgical and sacramental life. Fr. Daniel explained that they are able to offer what many parishes cannot, for example, daily confessions—just like their founder, St. Philip Neri, who transformed Rome in great part by hearing countless confessions every day. Now as then, it’s an individual effort focused on individual souls.

“Newman says, ‘the Oratorian fishes with a line, not with a net,’” Fr. Daniel went on, “and in the same way, we’re here just to try to bring souls one by one to God.”

Mass is celebrated multiple times a day, every day at the Oratory, a mix of English and Latin, sung Masses and quiet Masses. Confessions are heard before every Mass, and exposition and Benediction are a part of the daily schedule.

Centers of Hope

I pursued the idea of community as my conversation with Fr. Daniel continued. A common complaint, at least from the American side of things, is the lack of parish community: the support system for faith that includes regular activities in addition to Sunday Mass, such as study groups, social events, and the like. These are the types of things that help parishioners maintain their prayer lives, live the Faith in all aspects of their daily existence, and build relationships. Such a life is particularly crucial for integrating newcomers into the parish.

Fr. Daniel affirmed that the same “community problem” exists in England, in part due to the current parish structures which involve a limited number of priests who exhaust themselves covering large parish territories with dwindling attendance.

In contrast, Fr. Daniel proffered the idea of “centers of hope,” of which the York Oratory is but one example. He identified St. Mary’s in Warrington as another, diocesan parishes like St. Patrick’s in Soho Square in London, and monasteries, which historically have always been centers of learning, culture, and community.

Such “centers of hope” are oases—gardens, you might say—that offer the full cornucopia of Catholic life. Like we saw in the aforementioned St. Mary’s, they offer a place to go, to be, to be from, and to come back to. They are fully woven into the parishioners’ lives rather than being just a Sunday or twice-a-week obligation. They are a natural center of gravity, and a necessary lifeline in a world that, as Father spoke of it, is essentially hostile to Christianity.

I mentioned with fondness my own diocesan home parish back in upstate New York, which was the center of life for my friends and our families as we grew up.

“And that changes everything,” Father confirmed.

It simply isn’t enough for people to come to Mass for an hour on Sundays, he explained. The Faith can’t be nourished and sustained that way.

“People can’t live the Faith in isolation,” he said.

How Does Your Garden Grow?

Fr. Daniel noted that they have an extraordinary number of young converts: people in their teens, twenties. That’s an accomplishment any religious institution would be proud of, but he was quick to deflect any credit.

“In a sense, it’s nothing to do with us,” he explained,

“We just turn up. We just do what we’re meant to do. I’m not saying we’re doing it especially marvelously or anything but we just do it. But God brings them. In other words, there’s something innately attractive about the Gospel, if you will just proclaim it and celebrate the liturgy worthily and be there, people will come.

They live in a world which is totally relativistic, hedonistic, everything—and yet, there’s a steady stream of people who turn up on the doorstep who want the Faith and who don’t want a kind of watered-down faith, they want the authentic Christian Faith.”

The steadiness of this unhurried approach was a significant point to me. I made a comparison so obvious it was almost cliché: that the Oratorian approach, at the Oratorian pace that I’ve spoken of before, was a lot like the garden growing around us.

“Yes, it’s very much like a garden,” Fr. Daniel agreed. “Father Stephen, who does the gardening, in a sense he just enables it.” It was the grace of God that provided the growth, the Gospel itself that was the source of life.

I then went off on a minor personal tangent about the complaints I supposedly hear from young people who search for community but who—according to my limited, log-clogged viewpoint—don’t do much to invest in it.

I said something about being intentional about community, investing in it, giving it time, “doing it on purpose.”

“But in a sense what you don’t need is a strategy,” Fr. Daniel said, gently redirecting my line of thinking once again and disarming my obviously strong opinions on the subject. He went on:

“There’s always people saying, ‘The quick fix is if we do this and do this…’ There isn’t a quick fix. You just have to live the Christian life as best you can and let God’s grace do the rest.”

Much like nature, these Oratorians are never in a hurry, yet somehow God’s work is always accomplished.

Going to Heaven in a Coach-and-Four

Fr. Daniel described in more detail the kind of full Christian life that the York Oratorians were striving to grow here at St. Wilfrid’s.

He first called on the example of their founder, St. Philip Neri, whose way of life provided the lasting pattern for his followers during his own time and down through the centuries.

As you might recall from your introduction to St. Philip back in Dublin, he was known as the “saint of joy,” who evangelized by offering that full Christian life, striving to bring the grace of God into every corner of his disciples’ lives.

Get-togethers hosted by St. Philip tended to involve prayer, fellowship, recreation, laughter, singing. He planned outings, picnics, games, fun. He recognized that we needed to be Christians in everything we do, at every moment—rather than only “doing the Christian thing” by making it to Mass on Sundays.

Adapting St. Philip’s methods to our own day, the York Oratorians have all kinds of things going on. You can join scholas, bible studies, prayer groups, even a bellringers’ club! Some learn Latin together, others read Dante. They put on Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream to celebrate the Queen’s Jubilee.

“And actually that’s all about giving people a very broad cultural experience—that beauty and truth go together. You can’t sacrifice either one of them actually, and goodness as well. Truth, beauty, and goodness are the three things that a parish ought to be living. And so the Oratory activities aren’t quite what you might expect in an ordinary parish.”

Fr. Daniel Seward

Fr. Daniel gave an example of the type of activity that really illustrates this idea of truth, beauty, and goodness—an activity they have emulated to some degree in York. St. Philip would often host “musical oratories, ”performances that were halfway between a liturgical service and a concert.

“That kind of bridge between the good elements of the secular world and the holy is what the Oratory is about,” Father said. “It’s about using all of the good things that we find—music, art, literature, architecture—and using those then to draw people upwards.”

“It’s why St. Philip was said to have driven people to heaven in a coach-and-four.”

(Editor’s note: a coach-and-four is a coach drawn by four horses. Very fancy!)

Listening to the description of life at this Oratory certainly makes you want to be a part of it. The richness of life there was attractive beyond description. And wasn’t this always how it was supposed to be?

“God created us body and soul to live human life to the full,” Fr. Daniel said. “And the Philippine model is an example of how to do that.”

It’s a model that seems uniquely poised to renew the Faith in a time and place where it’s easy to get discouraged by the post-Christian landscape.

“But that’s what we look at all over the world,” Father said. “You can paint a gloomy picture if you just look at certain statistics. But then wherever you go you will find little beacons of hope.”

I’d certainly found a lot of beacons of hope since landing in the British Isles but a few days before. It was nearly impossible to be discouraged when you were on the grounds of these spiritual lighthouses, seeing with your own eyes the life that was within them—a life that is freely given to anyone who desires it.

The York Oratory was only the beginning of my discovery of that city’s rich Catholic heritage. York—and Yorkshire in general—is a segment of England truly steeped in Catholic history.

We’re going to need more than one article to explore it, so join me next time for a virtual tour of the Shrine of St. Margaret Clitherow and the Bar Convent, which houses a relic of her hand and artifacts from England’s great persecution.

Before I left the Oratory and continued on my adventure, I couldn’t resist taking pictures of that beautiful garden. It really was one of the finest you ever saw. +