“Are we not perhaps all afraid in some way?”

Pope Benedict XVI

I was twenty years old, numbed to my faith, and very afraid. I was riddled with doubt, and ashamed of myself for it. It was my junior year of college and I was in the middle of a course on modern theology.

As a student of the Great Books, each Tuesday and Thursday I would climb three flights of stairs to listen to lectures on Kierkegaard, Edith Stein, John Henry Newman, etc. These were beautiful and powerful lectures on fundamental Catholic beliefs, but as I said: I was numb, doubtful, and afraid.

Then I was assigned to read Introduction to Christianity by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (Pope Benedict Emeritus XVI ) and quickly encountered an articulation of faith that resonated with me, not simply because I related to it, but because it rang true:

No one can lay God and his Kingdom on the table before another man; even the believer cannot do it for himself. But however strongly unbelief may feel itself thereby justified, it cannot forget the eerie feeling induced by the words “Yet perhaps it is true.” That “perhaps” is the unavoidable temptation in which it too, in the very act of rejection, has to experience the unrejectability of belief. In other words, both the believer and the unbeliever share, each in his own way, doubt and belief, if they do not hide away from themselves and from the truth of their being. Neither can quite escape either doubt or belief; for the one, faith is present against doubt, for the other through doubt and in the form of doubt. It is the basic pattern of man’s destiny only to be allowed to find the finality of his existence in this unceasing rivalry between doubt and belief, temptation and certainty. Perhaps precisely this way doubt, which saves both sides from being shut up in their own worlds, could become the avenue of communication. It presents both from enjoying complete self-satisfaction; it opens up the believer to the doubter and the doubter to the believer; for one it is his share in the fate of the unbeliever, for the other form in which belief remains nevertheless a challenge to him.

Introduction to Christianity by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger

“…if they do not hide away from themselves and from the truth of their being.”

The temptation to hide away from myself, from the very truth of my being, and deny my own doubt was a strong temptation—one which I fell into repeatedly; one that perhaps led to the resigned staleness that currently trapped me. But this forthright and clear articulation of the tangled relationship between faith and doubt caught me off-guard and shook the stale numbness from me. I could not stop reading.

Page after page of Introduction to Christianity continued to disarm me.

Cardinal Ratzinger, beginning his opening chapter with a section titled “Doubt and Belief—Man’s Situation Before the Question of God,” was not afraid of his own humanity. Rather, he recognized—not from distant empathy but from personal experience—that we are creatures who doubt, which also means that we are creatures capable of faith. Not only did Ratzinger address my own particular and painful concerns, he gave words to silent sensations I had experienced, ones seemingly so interior that they appeared to my young and fearful heart to be isolating, wrong, and irreverent.

In the face of the radical truth of the Incarnation and the glory of the Catholic faith, my own doubts and concerns seemed silly and even shameful. However, Cardinal Ratzinger did not share my shame nor my sense of benign silliness. When faced with his humanity and our own, Ratzinger chose to look at it, undressed of any pretense or falsehood, and not to separate his considerations of faith from his considerations of the more painful experiences of our nature.

Ratzinger’s insistence on addressing our humanity is radical. It’s radical in its character, which chooses to concern itself with truth, not control.

For myself as a student, this was deeply moving. The writings of Cardinal Ratzinger slowly revealed to me that I was afraid, both of what I didn’t know, and—more difficult to face—that which I did know.

I hadn’t realized that I had become split. I had always been a fervent reader and student who liked to know things. As I got older and pursued the study of the Great Books in college, I did so out of a desire to be exposed to all the important ideas, Christianity among them.

Except, I didn’t know what understanding was; I didn’t realize its depth. Alongside modernity, I had let myself become convinced that to “know” something was to verify it. It was safer that way.

To not know absolutely was to admit something out of my control, and required that I open myself up beyond my own understanding. Frankly, it asked me to do something that I was too proud to do: admit to the limits of my understanding.

For myself, this is what led to my paralysis of fear. I only knew truth as something that could be verified, and I could not verify God. God is not seen. He is not observable, measurable, or a stable constant that we can experiment with.

But I desperately wanted to believe. So I became split. I wouldn’t look at my faith or the reality of God with my eyes open. I was afraid. Afraid that if I did, my precariously-held faith, the morality and tradition of my childhood, would somehow fracture; that I would find some fine crack along the foundational seem, threatening its integrity.

What began as a desperate grasp to secure my faith became the precise thing that kept me from faith at all. I was created with an intellect, reason, and senses, yet I was not allowing these innate aspects of my nature to have a role in my belief. Without these necessary parts that fed and watered the whole, my personal faith slowly withered away.

What Pope Benedict XVI reminded me was that my faith was not dependent on me alone. That my intellect and reason were not wholly private mechanisms, but rather gifts that could be used to open myself up to truth, a truth that is always received. Eroding my modern convictions of understanding and evidence, he replaced them with true reason and reverence.

He spoke directly to my desperate grasp on reason and faith when he said,

Men need more than just grasping and holding; they need understanding, which gives power to their actions and their hands; they also need perception, hearing, reason that reaches to the bottom of the heart. And only when understanding remains open to reason, which is greater than it is, can it be genuinely rational and acquire true knowledge. If you do not love, you do not know (1 John 4:8). Of course knowledge is important, but when they are regarded as sufficient in themselves, they become not only empty, but dangerous as well.

Homily for May 16th, 1985, in Ordinariatskorrespondez, no. 15

Pope Benedict’s distrust in a knowledge that is purely scientific was not rooted in ideological concerns, but human ones. Pope Benedict recognized the dangers of the over-rationalization that our world presented to us: it makes us lonely. It convinces us that we need to understand wholly on our own and with our own terms.

Being young and proud, my temptation was to seek what knowledge I could on my own and to lock myself in a reality where I needed to prove everything if I wanted to consider it true. And I knew I could not prove my faith, so I did the other extreme. I locked myself apart from faith, thought of it as simply something “other” that I must blindly believe, something that is so distinct from me and my material reality that I simply must shut my eyes and believe without participation.

As a child, I had not carried this same burden of proof. Rather, I simply believed. My parents taught me about the world and about Jesus Christ, and I trusted them and believed. With childlike wonder, the person of Christ didn’t need to be verified, for I knew love from my family and my home and trusted that love was real in the person of Christ: “Jesus loves me this I know…”

But the reality of love can sometimes be diminished. We experience pain and find that our trust becomes strained. For my part, I hid from this straining by attempting to secure myself in knowledge.

What I forgot was precisely what Pope Benedict reminded me of, that “faith is located in the act of conversion, in the turn of one’s being from worship of the visible and practicable to trust in the visible” (Introduction to Christianity, pg. 88).

“…trust in the visible.”

I had let my ability to trust fade. Rather than set my horizon of trust on the Father, who never fails, I had placed it in the world, which can distort and betray.

So I recoiled inward. But trust requires another. It requires one to open oneself up to the world around them. My own heart warmed at this reminder: I am capable of being opened up.

Not only that, but to be opened up would mean to be open to being raised up! Ratzinger continued,

the phrase ‘I believe’ could here be translated as ‘I hand myself over to’, ‘I assent to’. In the sense of the Creed, and by origin, faith is not a recitation of doctrines, an acceptance of theories about things of which in themselves one knows nothing and therefore asserts something all the louder; it signifies the all-encompassing movement of human existence.

Introduction to Christianity by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger

I knew all of this, of course. There was a faint and dull ringing at the familiarity of this sentiment. A whisper of the recollection of the words: “Then Jesus told him, ‘Because you have seen me, you have believed; blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed.’”

But what I had not accounted for was my pride. My reduction of faith to either a mystical spirituality with no foundation in reason or to concrete and verifiable dogmas meant for recitation, only served to protect myself from my own limits. It kept me comfortable and unaware of my ignorance.

My staleness and paralysis was caused by fear, but worsened by a lack of love. Relying entirely on myself and my intellect, I lost the wonder and trust that opens one up to another and ultimately, to love. These words of Pope Benedict challenged me with love, to begin to love again.

Pope Benedict’s life and papacy was urgent on this matter: the necessity of love. While his ability to capture the crisis of faith and reason that confronted us was profound, it was for the sake of fostering love.

He writes:

When the Bible says: ‘In the beginning was the Word’, it says much more as well. It is not a mind that, as it were, governs the universe like an idea in higher mathematics, while remaining itself untouchable and univocable; this God, who is truth, spirit, mind, is likewise Word, that is he is also a gift. He is the constant new beginning, and this also a new hope and a new way.

Co-workers of the Truth by Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, pg. 48

Pope Benedict’s return to the reality of Christ as the Word, spoke to me deeply, and I believe it will speak to the core of all who live in an age inundated with mere information.

What Pope Benedict continues to insist upon is that we are not alone. The Word necessitates a speaker and a listener, it necessitates a relationship, something dynamic and alive. It offers itself as a mediator between the world and how we understand it; the Word makes reality understandable to us, it is the only means to truly understand our lives and ourselves.

In calling us back to the Word, Benedict recognizes and respects our capacity for mystery and our capacity for wonder. He does so not arbitrarily so as to make an interesting theological point, but necessarily to aid us in the recognition of God.

Pope Benedict, humbly recognized that God does not remain as the Word, but becomes a word that is named. He says,

When God names himself after the self-understanding of faith he is not so much expressing his inner nature as making himself nameable; he is handing himself over to men in such a way that he can be called upon by them. And by doing this he enters into co-existence with them; he puts himself within their reach; he is “there” for them.” God has offered Himself as the Word, as the mediator between us and reality, but He has also named this Word in the person of Jesus Christ. Love is no longer abstract and distant, but true flesh and bone. We are not asked to put trust in an unrecognizable force but in a person.

Introduction to Christianity by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger

As Christians,

We have come to believe in God’s love: in these words the Christian can express the fundamental decision of his life. Being Christian is not the result of an ethical choice or a lofty idea, but the encounter with an event, a person, which gives life a new horizon and a decisive direction.

Deus Caritas Est, Pope Benedict XVI, 2005

In our fear, we look out at the unknowns that we encounter daily, and can try to cover over them with “lofty ideas” and the false security of evidence, but it leaves us feeling unsettled and without meaning. With Christ, these unknowns become encounters with a mystery, but the mystery of a Person, of a love beyond what we could ever know—and He meets us every time.

As Pope Benedict prepared to die, he prepared to enter the biggest mystery of our lives: what happens when earthly life ends. Despite recognizing that he has “great reason for fear and trembling,” he is

nonetheless of good cheer, for I trust firmly that the Lord is not only the just judge, but also the friend and brother who himself has already suffered for my shortcomings, and is thus also my advocate, my “Paraclete.” In light of the hour of judgment, the grace of being a Christian becomes all the more clear to me. It grants me knowledge, and indeed friendship, with the judge of my life, and thus allows me to pass confidently through the dark door of death.

Letter of Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI

When life is lived as Pope Benedict lived his, with experiences of doubt, misunderstanding, and mystery—and is met not with anxiety and its firm grasp of control, but with love, trust, and friendship with the person of Christ—it is lived in a way that prepares you for death and judgment. It prepares you in the way of love.

With Pope Benedict’s passing, I am reminded again of why his writings transformed me so noticeably: he spoke to my fear and doubt, but did not dismiss it. Rather, he confidently reminded me that Christ can handle these things, that Christ can handle me, as I am. The gift of the Catholic Faith should not be tossed away with any passing doubt, but rather is best when bearing the weight of doubt, which helps remind us of our finitude and limits, and teaches us the necessity of trust.

Of course we are all afraid—we are so very limited!

Along with Pope Benedict, let these reminders of our limits draw us closer to Him Who is without limits. The Person of Christ is waiting for us with love and He will comfort us in our affliction and fears.

These words of Pope Benedict will stay with me forever, but so will the person of Pope Benedict, who loved so well, served so faithfully, and guided me home:

“Are we not perhaps all afraid in some way? If we let Christ enter fully into our lives, if we open ourselves totally to him, are we not afraid that He might take something away from us? Are we not perhaps afraid to give up something significant, something unique, something that makes life so beautiful? Do we not then risk ending up diminished and deprived of our freedom? . . . No! If we let Christ into our lives, we lose nothing, nothing, absolutely nothing of what makes life free, beautiful and great. No! Only in this friendship are the doors of life opened wide. Only in this friendship is the great potential of human existence truly revealed. Only in this friendship do we experience beauty and liberation. And so, today, with great strength and great conviction, on the basis of long personal experience of life, I say to you, dear young people: Do not be afraid of Christ! He takes nothing away, and he gives you everything. When we give ourselves to him, we receive a hundredfold in return. Yes, open, open wide the doors to Christ – and you will find true life. Amen.”

Homily of Pope Benedict XVI, Mass for the Inauguration of his Pontificate

Thank you for everything, Pope Benedict. May you rest in peace!

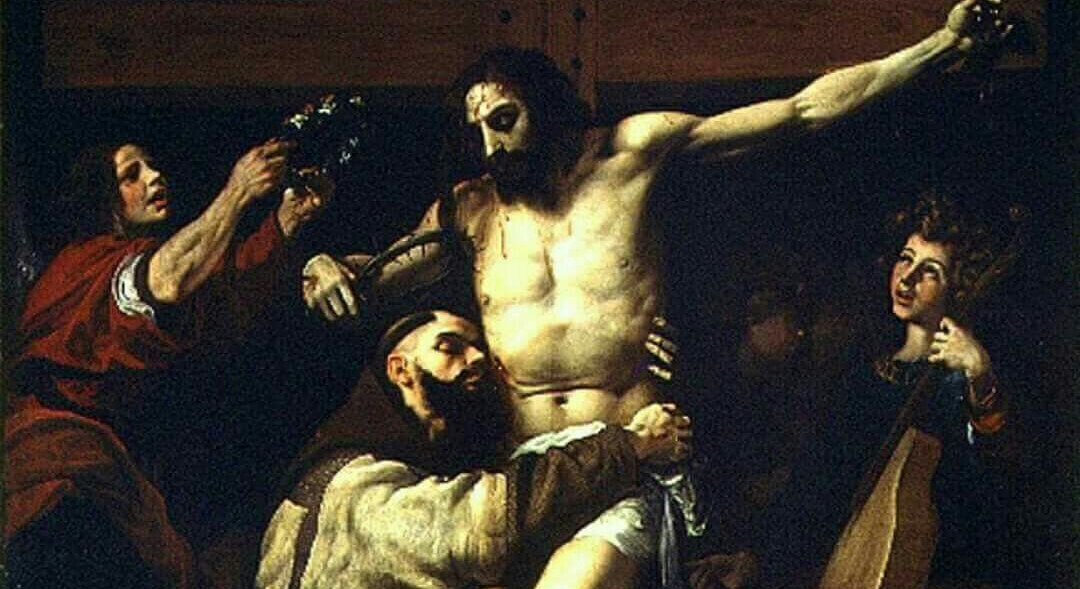

Feature image: Pope Benedict XVI greets pilgrims on Mary Ward 400th Jubilee. Photo by Sergey Gabdurakhmanov/CC BY 2.0.