On December 9th, we celebrate the feast of St. Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin, the visionary of Guadalupe. It was to this humble Christian Indian that Our Lady appeared in 1531. It is his tilma that hangs in her basilica in Mexico City.

Who was this man? What do we know about his people and the culture that formed him?

If we want to understand the Blessed Mother as the Virgin of Guadalupe, we need a proper understanding of the man she appeared to and the people from which he came.

In this article, we’ll read about the world of the Aztecs, their beliefs and symbols, Juan Diego himself, and heaven’s answer to his troubled kinsmen.

Empire of Blood

Juan Diego was an Aztec Indian, a member of the Chichimeca people who spoke the language Náhuatl and lived near modern-day Mexico City.

The Aztec people of his heritage have a well-deserved reputation for absolute brutality.

During the dreadful dedication of the great temple in Mexico City in 1487, for example, more than 80,000 men were sacrificed over the course of four days.

Human sacrifice was a central feature of their religious ceremonies—the result of a dark perspective of the divine, characterized by violence and fear.

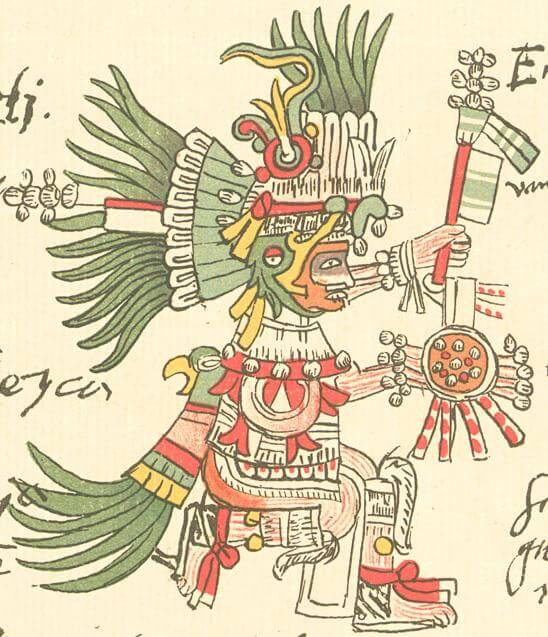

Let’s take a look at some of the religious imagery of the Aztecs, both in the meaning of specific motifs and the worldview that can be gleaned from them.

The eagle and the sun

The sun was believed to be the greatest Aztec god. He was represented by an eagle who carried the sun through the sky.

Each day, this eagle did battle with the “god of the night” (represented by a jaguar) for control of the sky. Red clouds in the morning were interpreted as the blood of the combatants. Even something as peaceful as the morning was infused with violence and conflict in the Aztec mind.

The snake and the earth

The earth was seen as it usually is in pagan cultures—as a mother-goddess. From her, the Aztecs thought, the eagle/sun and jaguar/night were born, rising as they did from the earth’s horizon.

But this earth-goddess was hardly a welcoming and sympathetic figure; rather, she was a repulsive creature.

In her depictions, she appears decapitated with two snakes coming out of her neck and forming a new face. Her arms are also cut off, with snakes emerging from them. Her name means “She who wears a skirt of snakes,” and indeed, her attire is serpentine.

Why snakes?

Well, to the Aztecs, the snake paradoxically symbolized life—hence the dominance of snake imagery in the portrayal of mother earth, seen as the giver of life and goodness (despite her awful appearance).

In fact, the snake imagery goes further: this goddess wears a snake as a girdle, indicating that she is pregnant, and a snake connects her to the earth like an umbilical cord.

A strange idea, indeed, that a venomous predator should be seen as a life-giver among this people!

The moon—another high-level female goddess—is equally ghastly.

Her head, arms, and legs are all cut off, evidence of her involvement in the night god’s perpetual war against the sun.

The phases of the moon (which, most of the time, is only partly visible) were believed to portray her dismemberment.

Truly this was a religion of darkness and violence.

Mercy Had No Face

These were a few of the primary religious figures that the Aztecs believed in: “deities” without love or mercy. Naturally, they feared their gods.

Consider the fact that two of their important female deities didn’t even have faces. Women are the embodiment of compassion, tenderness, and personal relationship—yet in the Aztec worldview, such mercy had no face.

The Aztecs also believed in a sort of karma-ish reciprocity between the human and divine. They thought that whatever you did on earth had an effect on the events of the divine world.

The practice of human sacrifice sprang from the belief that humans needed to continually give life to the gods. The sun also “needed warriors” to help him battle the night.

These “gods” always repaid evil deeds with punishment, having little mercy for the sinner. Bad events were seen as a sign that a god was unhappy and needed to be placated.

Hence these unfortunate Aztecs were continually striving to counteract the “anger of their gods.”

Violence was a way of life. The sacrifice of one’s own life or that of one’s children was an accepted norm in order to maintain the order of the universe and save oneself and one’s people from negative repercussions. Violence and death ruled their lives from start to finish.

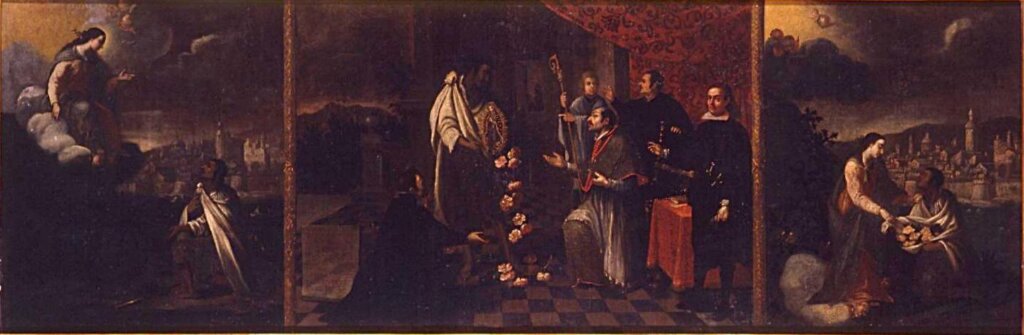

In the 15th century, some time after the Spanish had landed on their shores and encountered the Aztec people for the first time, Franciscan missionaries were struggling to bring the truth of Jesus Christ to these troubled people.

In fact, the heroic efforts of Bishop Zumárraga and his missionaries produced little fruit. There were a few conversions—that was all.

Furthermore, various factors related to some corrupt Spanish officials were turning the Aztec people against the Spanish—making massacre a real possibility.

[This new] administration was one of the most disastrous epochs in new Spain and one of great difficulty for Bishop Zumárraga. Cortes had returned to Spain just previous to this and in his absence no limits seem to have been placed to the abuses of [the current Spanish auditors]. They impoverished the Indians by taxes, sold them into slavery, branded them with hot irons, sent shiploads to the Antilles, offered violence to Indian girls, and persecuted with incredible fury the followers of Cortes.

Bishop Zumárraga, as Protector of the Indians, endeavoured vainly to defend them.

The Catholic Encyclopedia

Fearing for the lives of his missionaries, and seeing the imminent collapse of all their good-faith efforts, the holy Bishop turned to the Blessed Mother and begged for her help. Send a sign, he pleaded, that a miracle is about to occur!

Our Lady heard his prayer.

And she would answer it through an unexpected messenger.

Juanito

Juan Diego was born in 1474—long before the Aztec Empire met its match in Hernan Cortes in the 1520s, and even before the subsequent evangelization of the region by Franciscan missionaries.

His native name, Cuauhtlatoatzin, means “He who talks like an eagle,” an appellation both curious and significant, as eagles were creatures of enormous importance in the Aztec mind.

In 1524, Cuauhtlatoatzin and his wife converted to Christianity when it was brought by the Franciscans. He was baptized “Juan Diego.”

A devout man, he traveled great distances to hear Mass and attend catechesis. He was hardworking, well-respected in his community, probably a widower by the time of the apparitions, and caretaker for his aging uncle.

The Apparitions

On his way to church one day, Juan Diego encountered a beautiful young maiden at Tepeyac Hill, former site of an ancient temple to the awful “earth goddess” we read about earlier.

To Juan’s eyes, this maiden must have looked familiar, yet very, very different.

She was one of his own people, an Aztec of great standing judging by her attire. He would have recognized the color she wore—a mantle of jade—as the color of Aztec royalty. (The jade stone was sacred to the Aztecs as representative of the divine and the afterlife.)

The pale red of her dress was the color of earth, but she was nothing like the cruel, headless earth goddess formerly worshipped on that spot.

Furthermore, this Lady whom Juan met had a face. A human face.

The warmth of an earthly mother reflected in her pale red dress, which was the color of the earth and of the rosy dawn. Her radiant features were kind and compassionate, not fearful and cruel.

When she spoke to Juan in his own language of Náhuatl, she called him something incredible. She called him “Juanito”—“Little Juan.”

“Juanito, Juan Dieguito.”

This was a term of affection. She addressed him with love, as her own child. This was a new thing—a being from the heavens addressing humans with love!

She told him that she wanted to bring this love to all men:

“My son, I love you. I desire you to know who I am. I am the ever-Virgin Mary; mother of the true God who gives life and maintains its existence. He created all things. He is in all places. He is Lord of Heaven and Earth and I desire a church in this place where your people may experience my compassion. All those who sincerely ask for my help in their work and in their sorrows will know their mother’s near in this place. Here I will see their fears and I will console men and they will be at peace.”

She loves us?

She has love—for all people?

She wants a church where humans will not be sacrificed—but can bring all their troubles and sorrows without fear and receive consolation?

Truly this was an astonishing revelation.

But Our Lady’s most touching words were still to come.

“Am I not here, who am your Mother?”

Our Lady sent Juan Diego to the Bishop Zumárraga to pass on her request.

The Bishop, not yet believing Juan Diego, asked him for some time to reflect.

Juan reported back to the Lady, saying—in a profound display of humility—that she should send someone else to the Bishop, someone of higher standing.

But she insisted that he must be the one. Her little Juanito, though nothing in the eyes of the world, was her chosen messenger.

The Bishop then asked for a sign, and Our Lady told Juan to come back the next day to receive it.

But Juan’s uncle fell ill, and Juan could not meet the Lady that day.

The following day, when it was clear that his uncle was dying, he set out to find a priest.

Juan’s next move is quite endearing. He went around the far side of the hill in order to avoid running into the Lady, since he was ashamed that he hadn’t come back to see her the day before. He was also attempting to evade the Lady in his rush to get a priest for his uncle.

So Our Lady intercepted Juan, even as he tried to avoid her. She then said these beautiful words:

“Hear and let it penetrate into your heart, my dear little son: let nothing discourage you, nothing depress you. Let nothing alter your heart or your countenance. Also, do not fear any illness or vexation, anxiety or pain. Am I not here who am your mother? Are you not under my shadow and protection? Am I not your fountain of life? Are you not in the folds of my mantle, in the crossing of my arms? Is there anything else that you need?”

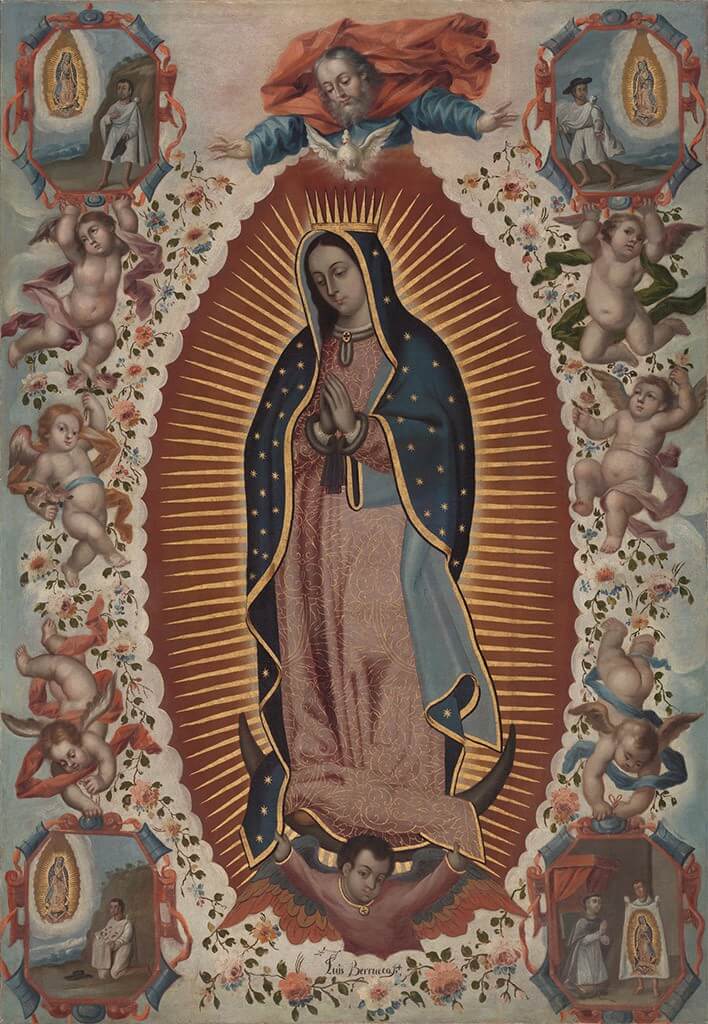

The Theology of the Tilma

Our Lady gave Juan the requested sign.

Castilian roses suddenly grew atop Tepeyac—a rose neither native to Mexico nor in season in December. The hill itself was in fact quite barren, not a place for roses at all.

After Juan gathered these beautiful, perfect roses, the Lady arranged them in his tilma herself, and sent him on his way.

When Juan arrived in the presence of the Bishop, he let down his tilma, showering forth the miraculous roses, and…gasp! the splendid image of Our Lady appeared on his garment before the astonished Bishop and all the other spectators. They venerated it in awe.

Now, this image was not simply a picture—beautiful as it was.

To the Aztec, this image preached a silent sermon. They immediately understood it. The image was rich with Aztec history and iconography, its every element carrying profound meaning.

The Blessed Mother was correcting the erroneous beliefs of this people—who are also her children—and leading them to God by a visual “gospel” that they could understand.

We’ll explore just a few of these elements here. (We mentioned some of these elements in our description of the Lady earlier.)

It would take a series of articles to investigate all the elements of the tilma, and there may be things about it that we have not discovered.

The sun

The sun, as mentioned before, was the greatest god for the Aztecs. He was often depicted with golden sunrays, wavy with snakes’ heads, snakes being the Aztec symbol of life.

Our Lady of Guadalupe eclipses the sun in her image, showing herself to be greater than this “sun god.” This eclipse is reflected in the blackness of the moon on which she stands.

The rays that emanate from Our Lady are not simply straight sun rays. Every other ray is a wavy line—directly reminiscent of the snake-rays of the (now-proven false) sun god.

The moon

The Lady stands upon the moon, which among other things represented the god of night (recall the jaguar in the myth retold above). She stands absolutely triumphant over darkness—doing what the sun god, in his daily battle against darkness, failed to do.

It is she who brings the final triumph of the day. The earth goddess was the mother of the sun god; Our Lady is the Mother of the true God, the true Sun, Who defeats darkness and death for good.

Human and heavenly

We have talked about Our Lady’s human face. In her image, it is clear that she is revealing herself to be human, rather than divine, yet still coming from Heaven.

Her eyes are downcast, while Aztec gods always looked straight forward.

Her hands are folded in prayer, so she is acknowledging a higher power than herself.

Her dress is the color of earth, indicating her humanity, while her sacred-green mantle is also dotted with stars, indicative of Heaven.

The angel who bears her up is holding both her green mantle and her red dress, signifying both humanity and sacredness.

The four-petaled flower

Our Lady’s dress is decorated with various floral patterns, each having their own meanings, yet there is a unique and distinctive flower that needs its own description.

This is the four-petaled jasmine flower.

It is associated with the sun god, whose main temple was built over a system of natural caves in the shape of a four-petaled flower. This four-segmented shape therefore represents the entirety of the cosmos, with its center in the sun god. The shape found its way into the Aztec calendar, in which the four cosmic segments are visible with the god’s face at the center.

The four-petaled jasmine flower, therefore, is a symbol of the highest divinity, the sun god himself, who is the center of all.

On Our Lady’s dress, this flower is found directly over her womb, indicating that she carries the true God, the true Center of the cosmos.

The One Who Spoke Like an Eagle

What happened after Juan Diego brought the image of Our Lady to the Bishop?

8 million native Mexicans converted to the Catholic faith. Devotion to Our Lady of Guadalupe spread throughout Mexico and the world.

Today the Shrine is the most visited Marian shrine in the world, bringing in millions of pilgrims every year.

As for Juan Diego, he spent the rest of his life living in a cell attached to the chapel where the image first hung. He swept the floor of the church and talked to pilgrims, living a peaceful and simple life.

“He who talks like an eagle”—that Aztec symbol of the highest divinity—had lived up to his name. He had spoken the words of Our Lady, the words of the Most High God, to the Aztecs and to the newly-forming nation of Mexico.

The entire Aztec culture—eagles, jasmine flowers, sun rays, the moon, seemingly every symbol—turned in tandem and proclaimed with a single voice the truth of the one God.

When the first Franciscan missionaries set foot in the Aztec Empire, they must have known that it would only be through the workings of God that the seeds they planted could possibly grow.

Their faith bore fruit. Roses grew in winter—and eagles talked.

What do you find most interesting about the Guadalupe apparitions?

How has Our Lady of Guadalupe been a part of your life?

We want to hear from you—please share your thoughts with us in the comments below!