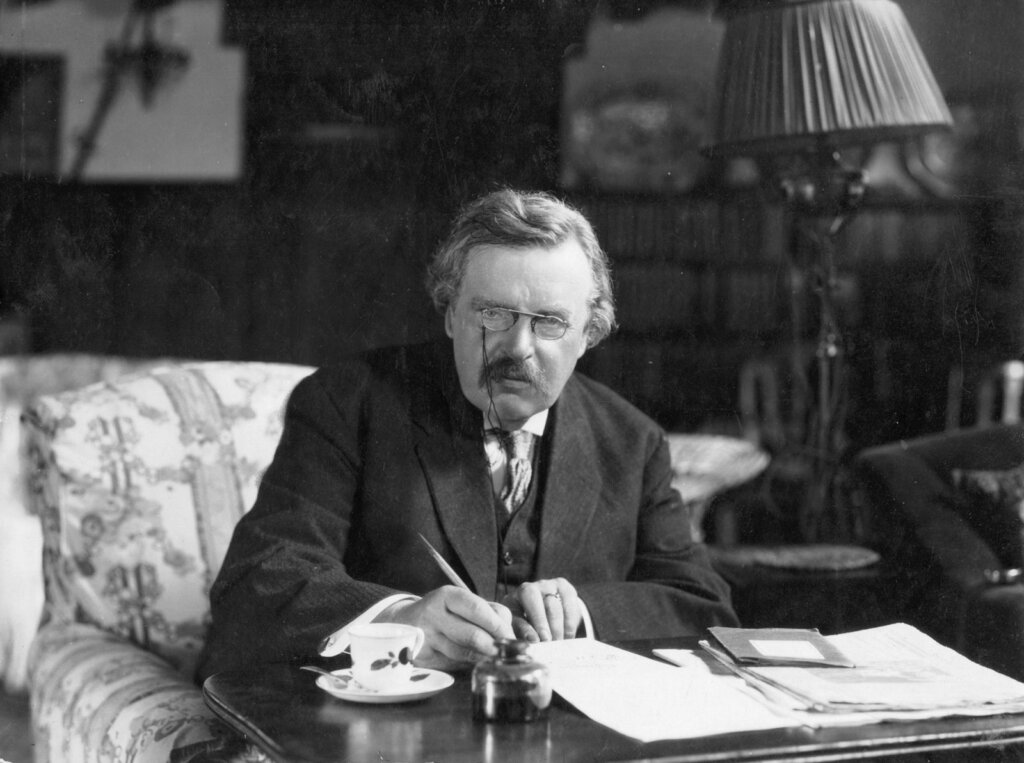

When a coworker messaged me a link to a riotously funny G.K. Chesterton essay about cheese, you can be sure he was not expecting it to be the genesis of the next War on Humans article.

The essay was supposed to be a simple diversion, infused with the laugh-out-loud wit that seems to be history’s gift to the Victorians. (I even feel wittier when writing about a Victorian.)

And yet, like everything else he wrote, Chesterton has a far deeper purpose than simply making us laugh, as noble an objective as laughter can be. Believe it or not, cheese is a vehicle for some quite serious and essential truths about the human condition.

In fact, Chesterton seems to be taking up the conversation about the War on Humans, which we have discussed in previous articles. It seemed only natural, then, that this article should be our next installment in that series.

What Can We Learn from Cheese?

So what are we really talking about when, along with Mr. Chesterton, we speak of the virtues of cheese?

Well, we might touch on culture and the loss of it in modern society (or to use Chesterton’s telling punctuation, “Modern Society”); we might chew on the concept of universality and its stark contrast to uniformity; we might talk about the Catholic (that is, “universal”) Church and how—whatever Modern Society might say of her—she has been the preeminent proponent of individuality and culture in every age of men.

Who knew that cheese had so much to offer? Let’s investigate.

Tales from the New York Pizza Wars

Describing a trip he took across the English countryside, in which he ate a meal of bread and cheese in four different counties in rapid succession, Chesterton says:

In each inn the cheese was good; and in each inn it was different. There was a noble Wensleydale cheese in Yorkshire, a Cheshire cheese in Cheshire, and so on. Now, it is just here that true poetic civilization differs from that paltry and mechanical civilization that holds us all in bondage.

Everywhere you go in the world—even within the boundaries of a single country or region—the culture is a little different. One of the main ways we sample this culture, as Chesterton demonstrates, is by partaking of its culinary offerings, which—if it’s really culturally-authentic cuisine—are endemic to the region.

Even from one town to another, the cheese (or whatever the favored victuals of a place happen to be) is going to have its own taste and flair, based on the ingredients natural to the place, its particular culinary concerns and limitations, its ethnic and historical idiosyncrasies, and whatever other mysterious ingredients go into something that just doesn’t taste the same anywhere else.

I couldn’t tell you why Texans use tomato sauce in their BBQ sauce and Carolinians use vinegar, but I can tell you that each side will fight to the death about which is better—because it’s tied to their identity and their home.

I’m from New York, so pizza is more important to me than BBQ, and if anything, the stakes are higher here and the fights infinitely more bloody—because the Italians are involved. I’m not a Manhattan city-slicker but rather a hillbilly from upstate, a place (not unlike the city) dominated by Italians and Poles throwing parish festivals full of their own versions of the best food in the world.

I will argue till I die that upstate New York Italian pizza is the best, not New York City Italian pizza. Didn’t you know there was a difference? There is, much like the variety among the cheeses of the different counties of England that Chesterton notes in Cheese.

It is these subtle differences that teach us what makes certain places what they are.

But why do these regional peculiarities carry such weight? What is their real importance, and what do we lose when they go away? Do we simply lose good pizza…or do we lose something else?

Following the Breadcrumbs of Culture

If you stop into any pizza joint in a part of the world that makes good pizza (i.e., upstate NY) and ask the owner the story of the place, you’ll probably get a good sit-down family yarn that goes back a few generations.

For example, good friends of my family in upstate NY have a regionally-known Italian restaurant known as Cortese Restaurant. It goes back decades, to three brothers of that name in the World War II era.

All three brothers were called off to serve their country in the war, but only two came back—Angelo died serving in the Navy. Now Angelo had had a dream to start a restaurant. This was less of a dream for the other two, Jimmy and Nate, at least until their brother died. But to honor their brother who had given his life for others, they and their family decided to found his dreamed-of restaurant, and it remains a Binghamton, NY favorite to this day.

Now wasn’t that a great story? Didn’t you learn about the past in a way you won’t forget? You thought you were simply eating pizza, but really, you were honoring a World War II hero, getting to know a family, connecting with the roots of a place. Your world became at least three generations bigger and older through partaking in local culture.

So we see that local culture gives us a connection to family, to the past, and ultimately, to faith. The Cortese family also happens to be Catholic like pretty much all other Italian immigrant families of yesteryear, and I can attest that their faith—and that of many other New York Italian families—is part of the reason I’m still Catholic today.

History, family, great stories, faith—all in a slice of pizza.

Now let’s see what happens if we take the pizza away.

How To Break a Culture

Bad customs are universal and rigid, like modern militarism. Good customs are universal and varied, like native chivalry and self-defence. Both the good and the bad civilization cover us as with a canopy, and protect us from all that is outside. But a good civilization spreads over us freely like a tree, varying and yielding because it is alive. A bad civilization stands up and sticks out above us like an umbrella – artificial, mathematical in shape; not merely universal, but uniform.

G.K. Chesterton, Cheese

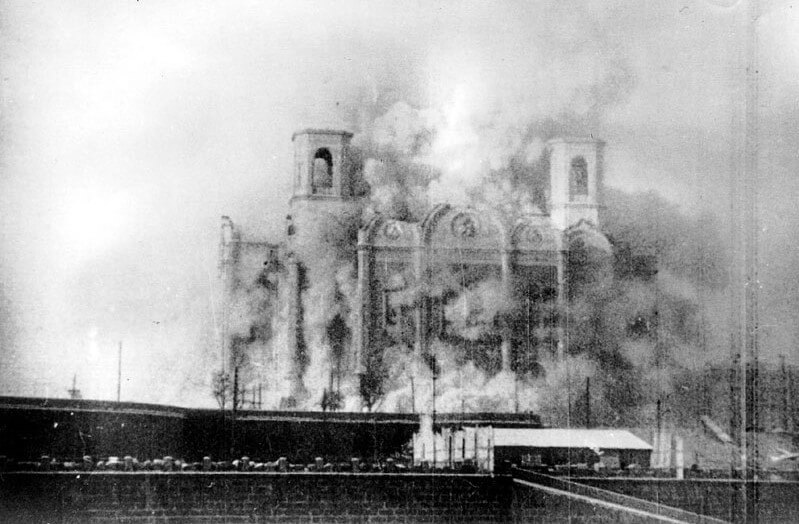

Communism is an apt case study in the importance of culture. After all, communists know the importance of it. They know that to destroy a civilization and recreate it in their own image, they must destroy its culture; that is, they must break its connection to its past.

As we have just seen, something as seemingly-trivial as pizza or cheese—or a local mazurka, or a glass of Viennese mélange—contains many lessons about the past. Such customs teach all kinds of communist “heresies” such as love of family, personal responsibility, and—especially heinous—faith in something other than the State.

So, naturally, in the “brave new world” of Communism, these customs are the first things that must go. A new, artificial “culture” must be installed that is uniform, tightly controlled, and contains nothing un-approved by said State—and this “culture” must only teach those lessons the State desires it to teach.

Humans cannot be allowed to grow on their own, like good cheese. If they’re allowed to do that, they’ll go on being humans, with all that human love of home, family, God, wine, food, song, story; with all the variety and nuance that comes when universal human goods—virtues and good values—are distilled in the vats of hometowns, home churches, home languages, home soil. All these things are poison (so the communists believe) and must be starved from the body politic so that it is free of its attachments and can embrace “the Future” freely.

Chesterton was not writing about Communism specifically in Cheese (he was writing before the Bolshevik Revolution exploded in 1917), he was simply describing trends he saw in Modern Society. But whether culture is attacked by outright political Bolshevism or by the nearly-imperceptible (and therefore more dangerous) changes in the trends of Modern Society, the results are the same for culture.

The result is that culture dies—and with it, all the things that it teaches us.

Well, friends and fellow-warriors of faith, looks like we’ve uncovered another of the devil’s tactics in the War on Humans. He hates culture because, in the end, good culture teaches us virtue, it binds us to our families, it inspires us to great things, it leads us to God.

Like everything else God has given us in this material world, culture is a method through which He draws humans to Himself.

The devil knows, therefore, that he must break culture.

Uniformity vs. Universality

Chesterton never says the word “catholic” in his essay, but anyone who is Catholic cannot help but smile when he describes the positive concept of universality in contrast to the negative concept of uniformity.

After all, the word “catholic” means “universal.” We call the Catholic Church the “universal” Church, because it encompasses all people, all places, all times. She is the Mystical Body of Christ, a living organism united to a Divine Head. We speak of the Communion of Saints, our living and real connection to all the faithful, living or dead.

Despite what Modern Society may tell you, the Catholic Church embraces all people. Here, you are judged not on your natural flaws, nor on your past, nor on your parentage; you are welcome if you profess the Faith and strive to live it.

We celebrate saints of all nations, colors, and languages. We honor French kings and Spanish princes, Scottish queens and Hungarian princesses, Syrian ascetics, Ugandan martyrs, Egyptian penitents, Chinese dissidents, Japanese samurai, shepherds, paupers, and mendicants from every age of humankind. Every saint is good, and every saint is different.

Every saint is good, because—through his profession of the Faith and his participation in the life of the Head—he is a viable member of the Body, filled with sanctifying grace and participating in Goodness Himself. He is “man fully alive,” responding to the natural and supernatural realities of his calling as a human being.

We can gather many different types of cheeses and call them all good if they participate in the basic qualities of good cheese. Similarly, we can gather many different types of men and appreciate them all, if they are good men.

But every saint is different because of the varied circumstances of culture, the peculiarities of his particular path to sanctity and sainthood. His culture, language, and circumstances are the individual means through which God called him to Himself—and by which He reveals Himself in a unique way to the rest of the world. We’ll never know all the infinite perfections of God, but we see more and more of His marvelous beauty with every saint we meet.

This is universality, and it stands in sharp contrast to uniformity, which is not always an evil but can be. It is good for an army to be uniform and wear a uniform, because the individual soldier must submit his personal identity, at least during working hours, to the overall functioning of the unit.

That is simply a requirement of his profession, and in a healthy society—that is, one that espouses universality—he is allowed to change into civies and be an individual when he gets home.

In an unhealthy society—one that rejects universality in favor of uniformity—we are all forced to put on a uniform, whether we signed up to be a soldier or not. We are never allowed to be an individual.

The uniformity is imposed, artificial, and lifeless. It is intended to control our actions from the outside in order to change our way of thinking on the inside—by force if necessary.

And we aren’t allowed to “take off” this uniform when we get home.

How to Save a Culture

Unfortunately, neither the subtle trends that Chesterton saw in early 20th-century England nor the grisly methods of Bolshevism are wholly unfamiliar to us, here in 21st-century America.

We have seen the ugly effects of “cancel culture” that not only divest us of our past, but vilify it—a move that would make any communist secretariat proud. Hate is more powerful and destructive than indifference. If we hate our past we will push it away forcefully, violently, and with all the unreasonable fervor of man-made religion. All kinds of things—monuments, people, history books, precious artifacts, businesses, lives—can be destroyed in one instant of self-righteous mob rage.

But perhaps even more distressing and destructive than momentary fits of passion is the slow draining away of culture. It happens quietly, drop by drop, in the background of daily life, in the dead spaces between the major news events that tend to occupy more of everyone’s attention. And worst of all, we find ourselves, consciously or not, deliberately or not, by force or by choice…assisting in the process.

Few of us have escaped the sadness of seeing a local coffee shop or restaurant close and be replaced by a chain. Fewer still can claim freedom from the common bondage of Amazon and online retailers, who are quickly putting local stores out of business. Jobs move natives away from their hometowns, starving towns of their economies and filling our American Babylons with rootless transients.

Authentic culture—our connection to our past—is being lost, bit by bit.

But that’s about as far as I want to go down the melancholic road of describing what has been lost.

This is not a dirge for the past but a call to preserve the future. This is not an idealist’s impractical plea to make sure everything we buy was made within a twenty-mile radius or implement totally-impossible changes to our lives—it is a positive encouragement to myself and all my fellow humans to take some simple steps to defend our cultures from the devil who wants to destroy them.

But how? How do we make a difference in a world that seems to be marching so uniformly in such a different direction?

3 Simple Ways to Preserve Your Culture

It’s a diabolical tactic to convince us that we do not matter as individuals and that our individual efforts can have no effect. It’s an effective lie that keeps us either indifferent to, or on the wrong side of, the battle.

We certainly don’t have control over the ill trends of the world, but there are some things we can do.

Here are a few simple, practical suggestions for preserving your culture and mounting an effective response to the devil’s attacks on it.

1. Learn about your own heritage. Especially in the USA, we all have a story of how we got here. Whether you’re descended from kings, coal miners, Irish immigrants, or horse thieves, you’re part of a story worth telling that likely includes large doses of hardship, trial, heroism, romance, family squabbles, and plain old good humor. Knowing our past helps us to treasure it, tell it, re-tell it, and preserve it.

At the same time, learning our story helps us to treasure ourselves. We are not accidents or atoms bouncing around the universe on our own. God called us into existence at a specific time and place, as a deliberate part of a particular story. As I once heard it described: “You are the result of the love of thousands.” In a world where we often feel insignificant, knowing our own story is invaluable.

2. Get to know the heritage of your local area, state, and region. This goes for homes and adopted homes, places of birth as well as places where we live now. Every place has a story and a significance, whether they be written in big history books or only in the memories of those who’ve lived there a while. Stop and read those handy history signs that often adorn the streets of small towns and RV parks that used to be battlefields. Visit a local museum or library. Best of all, take some time to sit on the front porch of an elderly neighbor who remembers how things used to be.

When I moved—not really by conscious choice, but by the workings of Providence—to the Carolinas, I was not as much of a fish-out-of-water as you might expect someone raised in New York to be. I’ve been a world traveler since I was born, and moving comes fairly naturally to me.

But more importantly, my dad is from Tennessee and every generation before him pretty much came from the same two border counties in southwestern Virginia/eastern West Virginia, a 180-mile bowshot from where I’m sitting right now. We are Appalachians by heritage, and I felt a sense of belonging when I came here.

So for me, Appalachian culture had particular meaning. I dove straight into a couple Appalachian cookbooks that showed up under the tree one Christmas. My biscuits still aren’t very good, but I make a mean cornbread. I’ve tasted the joys of wild muscadine, got a lot of Carolina red dirt on my shoes, and discovered that a bluegrass jam is the finest way to spend a Friday night.

Wherever you are, you’ve got the same sort of joys waiting for you—go explore them!

3. Support your local establishments. Everyone loves to shop local. This could take the form of restaurants like Cortese’s, coffee shops, bookstores, hardware stores, you name it. I’m especially fond of local farms, family businesses, and places that specialize in local dishes or art forms. Make a real point of giving these places your business regularly.

My family always used to get pizza on Friday nights from Mario’s Pizza (Cortese’s was too far away) as we rented a movie from Video King across the street, back when Video King was a thing. Video King is gone but Mario’s is still there because of dedicated locals who support it.

Getting back to culture is a big step toward getting back to our humanity and counteracting a particularly subtle and successful campaign against us in the War on Humans—a campaign that has been going on for quite a while, as evidenced by Mr. Chesterton’s thoughts (which were articulated in 1910).

God has placed us in our various places and times according to a wise and wonderful design. Love your culture, learn it, and support it.

And when you visit a new place, be sure to sample the local cheese. +

What region or place are you from? What is unique about it?

Did a particular person or place from your hometown have an impact on you growing up?

Many of us travel so much that we lose touch with our roots. What can we do to get back to our roots?