Artists who create beautiful artwork “not only enrich the cultural heritage of each nation and of all humanity, but they also render an exceptional social service in favour of the common good,” wrote John Paul II in his 1999 Letter to Artists. All the more important is the role of sacred artists, who enhance our churches and influence the culture.

In my article Return to Beauty, I interviewed four sacred artists—Ann Schmalstieg Barrett, Enzo Selvaggi, Cindi Duft, and David Clayton. They offered their thoughts about the modern world experiencing a new Renaissance. Now, they share a slice of their history, art, and mission, offering a glimpse into their passion for religious art.

Ann Schmalstieg Barrett

A tragedy led Ann Schmalstieg Barrett to become a sacred artist. Studying and copying sacred art from the masters brought her some solace after the sudden death of her husband Justin Schmalstieg. The newlyweds had been married for one year, one month, and seven days when Justin died during active duty.

On December 15th, 2010, during a night of heavy fire in Afghanistan, Gunnery Sergeant Schmalstieg, an Explosive Ordnance Disposal Technician with the Marines, was clearing the way for his team to return to base. He never made it back, because an IED (homemade bomb) detonated and ended the 28-year-old’s life. His sacrifice saved the lives of many Marines, and GySgt. Schmalstieg posthumously received the Purple Heart.

The couple had gone to high school together in Pittsburgh, PA, sharing an eight-year friendship before dating. The loss of Justin changed Ann as an artist. Tragedy has a way of forming souls and creative vision.

“Art is the language of the heart. Thus, I do not think it would be possible for an artist who experiences the loss of his/her spouse to ignore it in his/her art,” Ann shares.

Processing the pain of loss

Just two months before Justin died, Ann had been reading A Grief Observed by C.S. Lewis as research for her thesis project.

“Writing in the time after the loss of his wife, Lewis made the point that sorrow in reality is love, but in the context of loss,” she says. “Although it might seem obvious, it stands out from other approaches I had encountered. Identifying sorrow as love is vital because it affects the way in which we respond to the pain.”

For Schmalstieg Barrett, one blessing as an artist “is the ability to incarnate the reality of love through one’s work.” After losing Justin, she experienced waves of overwhelming sorrow triggered by flashes of memory, an anniversary, or even a particular song. In response, the artist brought her pain to the canvas.

“I would take that moment and strive to convey it through floral paintings,” she shares. “My aim was to express the experience with a sense of beauty because love is good, even when experienced in sorrow.”

To some, Schmalstieg Barrett’s paintings may appear dark. However, her widow friends share her experience and say that her paintings “offer a voice in a world that prefers to change the subject.”

Rather than feeling bitter about her loss, Schmalstieg Barrett focused on gratitude. Having shared a life and friendship with Justin was a great gift.

Her beginning as a sacred artist

After Schmalstieg Barrett’s husband died, the then-28-year-old made her first sacred painting, a master copy of the Sacred Heart after Pompeo Batoni (1708-1787). She created the artwork to enthrone their home—a place where she and Justin had planned to raise a family—to the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

When she took the painting to her priest to have it blessed, he was so impressed that he asked her to paint another traditional Sacred Heart for the church.

“Since then, I have sought to share the beauty of the faith and to support the prayer of others through my work,” she explains.

Schmalstieg Barrett works as an artist through commissions and independent projects. She also adjuncts at Franciscan University in Steubenville, OH, and teaches at St. Edmund’s Sacred Art Institute in Mystic, CT.

Oils and encaustic painting

Schmalstieg Barrett says she prefers to work in oils because of their beauty and because she finds the medium easy to control. Encaustic—an ancient medium composed of purified beeswax and damar resin—is another medium she enjoys.

“It is similar to oil in that it offers great potential in color quality,” she thinks. “Although I have less control with encaustic, the density of the medium itself allows for a quality of layering that adds a unique sense of depth to the work.”

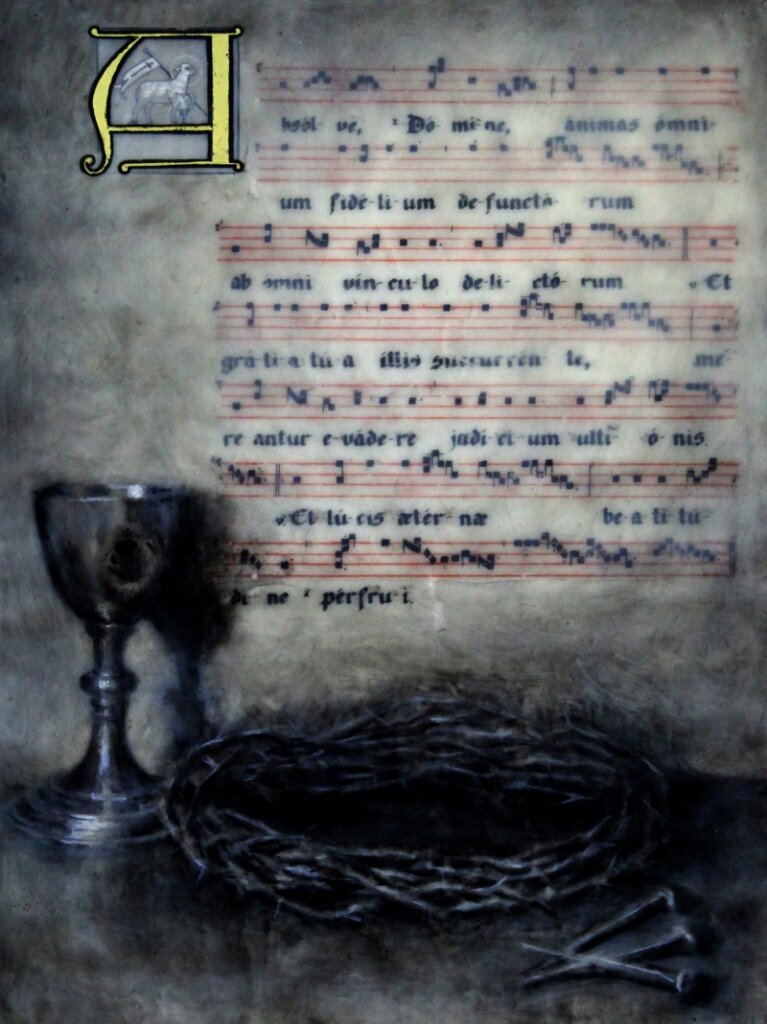

In 2018, to honor her late husband, she created a series of encaustic paintings exploring the Proper Chants of the Requiem Mass. She exhibited the encaustic chant panels with her floral paintings.

“I share the exhibit with parishes and university galleries whenever possible to provide a sense of the eternal love of God in the midst of our encounter with mortality,” she shares.

Ten years after becoming a widow, Ann married Mark Barrett. She’s grateful for Mark’s hidden influence on her work as well as her late husband’s.

Enzo Selvaggi

Eight-year-old Enzo Selvaggi stood gazing up at the ornate architecture of Rome, Italy. A stranger noticed him and stayed with the youngster until his parents found him. Selvaggi, who lived in Italy for the first 11 years of his life, says the Italian cityscape heavily influenced his artistic vision.

“Even as a child when I was drawing and putting together layouts of castles and houses, there was always a church and cemetery on the grounds,” shares Selvaggi, who now lives in CA.

He adds, “It was the place that I lived in that informed the imagination and situated the church at the center of the notion of the city.”

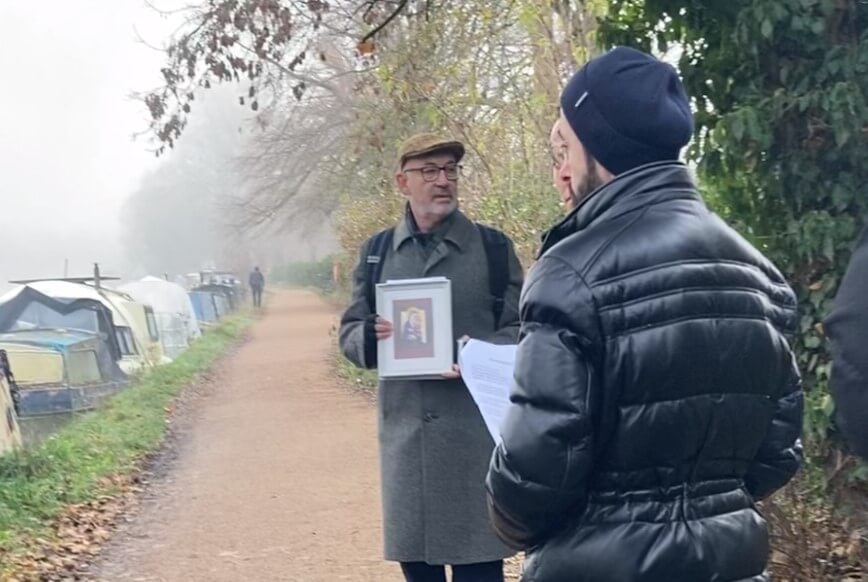

Photo courtesy of Heritage Liturgical

Many of his childhood designs took inspiration from the buildings he saw in Venice during family vacations. From childhood, Selvaggi sensed that architecture is sacred, but his actual focus on making churches beautiful didn’t start until about 2015.

First project: St. Michael’s Abbey

The church curator is self-taught, and he has taken classes from master decorators on faux finishing, perspective design by hand, and other courses to understand the language of classical architecture. He has also learned through working on projects.

On his first project, his company, Heritage Liturgical, collaborated with the Norbertine Fathers and iconographers to create murals and mosaics at St. Michael’s Abbey in Silverado, CA.

Photo courtesy of Heritage Liturgical

“That’s the best school in many respects,” says Selvaggi, who also helped design the organ at St. Michael’s. “Through the association with these projects and other experts, that’s how I come to do what I do.”

Photo courtesy of Heritage Liturgical

Make magnificent art

Many of Selvaggi’s projects harken back to a much earlier time. Currently, he has silversmiths crafting a monumental censer that’s going to swing in Christ the King Chapel at Christendom College.

“It’s about 20 centimeters taller than the censer at Santiago de Compostela,” he says. “They have to figure out how to do something that really nobody’s doing anymore.”

Photo courtesy of Heritage Liturgical

Besides curating beautiful art, another aspect of Heritage Liturgical’s mission is to educate Catholics about sacred art—why it has value and how to approach designing holy spaces. Selvaggi also teaches about the rupture in our cultural and communal understanding of why beautiful things are essential and how to craft them.

Selvaggi possesses a missionary desire to make magnificent art in collaboration with the finest artists and artisans. He desires to counter all of the ugliness and violence in the world with beauty.

Cindi Duft

Cindi Duft’s artwork beautifies many of Idaho’s Catholic churches. Duft, a native of Boise, aspired to create sacred art for churches, but first worked as a graphic designer for a decade.

“So even though at the time it felt like I diverged from my dream path, I built skills and patience and gained personal growth that I needed to be able to paint for churches,” she shares.

Duft also grew spiritually and gained a deeper knowledge of the Catholic Faith. She wanted to paint sacred art because she thought it was the best way to use her artistic talent.

“The gift that God had given me would be to give it back to Him through sacred art,” she says.

Church transformation

The Idaho artist has painted sanctuaries, altar panels, Stations of the Cross, and more. She feels most proud of the transformation of St. Paul’s Newman Center at Boise State University. Originally, the chapel had blank, uninspiring white walls. With input from Fr. Nathan Dail, the chaplain at St. Paul’s Catholic Student Center, she chose to depict Eucharistic symbols to restore a sense of sacredness to the church. She also used decorative patterns to unify the space.

“Now, when students walk into the student center, they immediately recognize it’s a sacred place. That it’s not like an auditorium or somewhere else on campus, but that they can immediately feel different and brings them into a spirit of prayer.”

Duft, with help from students, painted the social hall and exterior walls to help the building look more inviting.

“Hopefully, my art helps all who visit to connect with God and raise their hearts and their minds to pray—to recognize beauty and truth,” she shares.

David Clayton

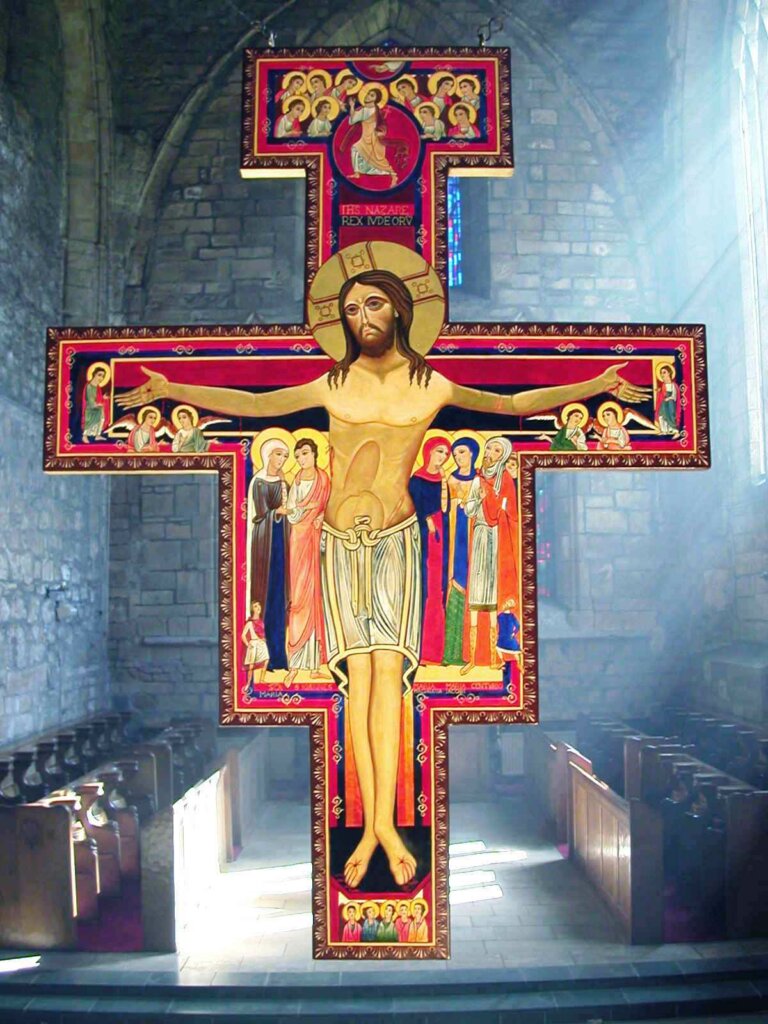

Beautiful art, architecture, music, and liturgy played a role in turning David Clayton from an atheist to a Catholic and then a sacred artist. In his early 20s, Clayton increasingly thought life seemed pointless, and he didn’t know how to find happiness. One Sunday, he walked into the Brompton Oratory in London and was struck by how everything was in harmony: the beautiful art, the music, and the liturgy.

“I remember as I heard the polyphony being sung by a wonderful choir, what popped into my head was, ‘This is what angels sound like.’ Then I looked up to see where the choir was, and I saw this angel on the ceiling in a mosaic. I could also smell the incense,” Clayton recalls. “So all the senses were engaged.”

He adds, “I didn’t instantly join the Church, but that impression stuck with me. And when I became Catholic, in 1991, at 31, Brompton Oratory was the church that I went to for many years.”

Feeling despair

Clayton grew up in England but earned U.S. dual citizenship and now lives in Princeton, New Jersey. Since his teenage years, he wished to become an artist. Even though he liked to draw and paint, his high school didn’t offer art classes, so he studied science and engineering. However, an undergraduate degree from Oxford and an advanced degree at Michigan Tech didn’t make him happy. Ultimately, despair led Clayton to seek solace in the bottle.

Ten years to conversion

With the guidance of a Catholic friend, he unknowingly began to walk the road to conversion. Part of that ten-year conversion process included taking art classes to improve his skills. Clayton ended up meeting the now well-known iconographer, Aidan Hart. Clayton had asked Hart to teach him about egg tempera paint, the medium used for painting—more officially known as “writing”—icons.

“I was really interested in early Gothic, Italian style art, but nobody taught that,” he says. “I thought iconography was the nearest thing. Maybe I can learn the techniques and then adapt them.”

Clayton wasn’t Catholic at the time, but after entering the Church, he returned to Hart to learn iconography. He felt drawn to the art form because of the icon’s theology and carefully-laid-out style.

“The integration of form and content is so complete that it pulls you in,” he shares.

Clayton’s embracing of the Catholic Faith allowed him to find his personal vocation as a sacred artist. He teaches iconography and art history classes listed on his website, called The Way of Beauty. He is also the Provost of Pontifex University, which offers an online Master’s Degree in Sacred Art.

The world needs sacred artists

Artists influence the way we view ourselves and the world. Sacred artists play an even more important role, shaping how we view God and His saints and fostering devotion. The world needs more culture-makers like these four artists, who strive to perfect their art to honor God. Hearts and minds are lifted to the spiritual realms through their sacred art.

Photo courtesy of Heritage Liturgical

Featured image shows Enzo Selvaggi working on an icon at St. Michael’s Abbey. Photo courtesy of Heritage Liturgical.