In 1992, I graduated from art school, but I don’t remember a lot of beauty—mostly art for shock value. In my early 30s, Vladislav Andrejev and his son Dmitri introduced me to Russian iconography. That moment made me contemplate why beautiful, expertly-crafted sacred art is vital to worship.

Beautiful art causes us to marvel; it makes us hope for more and aspire to become better people. Beauty points to the divine—all the more reason why sacred art’s purpose is to stir the soul.

Among recent popes, Pope St. John Paul II especially understood the importance of sacred art and artists. In his 1999 Letter to Artists, Pope John Paul II wrote, “Art must make perceptible, and as far as possible attractive, the world of the spirit, of the invisible, of God.”

More Catholic artists are taking the saint’s words to heart, using a brush and chisel to change the world.

New Renaissance

There is a budding new Renaissance in sacred art. After a period of dioceses uglifying Catholic churches and making them look dull, we are seeing a gradual return to beauty with more masterful artwork.

David Clayton, Provost of Pontifex University, which offers an online Master’s Degree in Sacred Art, also sees signs of a sacred art revival.

When Pope John Paul II wrote his letter to artists in 1999, Clayton felt there were few people he could talk to about the letter.

“Now there are artists interested in sacred art everywhere, and there are sacred art initiatives, especially in America. That’s one of the reasons I wanted to go to the US because it is much more vibrant and active in pursuing some traditional aspects of Catholicism,” says Clayton, who has both British and US citizenship.

However, he points out: “We are not out of the woods yet.”

“Like the life under the soil”

Enzo Selvaggi, the Creative Director for Heritage Liturgical, also senses a resurgence of interest in sacred art despite the atrophy of the larger culture, which he sees as increasingly against beauty.

“Underneath [a culture of destruction], there’s a lot of movement and activity—almost like the life under the soil in a forest—with a huge desire to respond with beauty and sacredness,” says Selvaggi, whose work comprises beautifying church spaces with a team of artists, sculptors, artisans, and architects.

He believes sacred artists are “rebuilding something that was dormant.” However, they are creating without guidance because of lost knowledge.

“We’ve lived for two generations, at least, of things being destroyed,” he points out. “So we’ve not seen beautiful churches being built.”

The More Profound Meaning of Sacred Art

All beautiful art points to God. In 1990, I worked at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. The museum hosted the largest Impressionist exhibition ever held in the United States at that time. Over 150 paintings, drawings, and sculptures were on display. Lines of people, snaking out the doors for blocks, stood waiting to see artists including Claude Monet, Paul Cézanne, Mary Cassatt, and the father of impressionism, Camille Pissarro.

If I ever doubted the popularity of Impressionism, seven months of droves of art lovers visiting the museum convinced me that it’s one of the most admired movements in art. I bring up the Impressionists because there is a place for and a need for all types of beautiful art.

But whereas the Impressionists aimed to capture light, color, and atmosphere, the purpose of sacred art is for worship, to inspire spiritual contemplation and adoration of God.

Sacred artist Cindi Duft, from Boise, ID, says, “One of the things about Catholic art is that you’re painting within a tradition. It’s supposed to look Catholic.”

She adds, “In other kinds of art, the important thing is to be so original; it’s more about the artist and what he or she is communicating.”

In iconography, the artist is constantly invoking God. Every line, color, and stroke has meaning directed towards the divine.

“With sacred art, you’re painting for a purpose, not for yourself or to have somebody recognize [you],” she says. “I don’t care if people recognize that it’s my art. I don’t even sign my work.”

Ateliers and Sacred Art Workshops

Ann Schmalstieg Barrett believes we live in a time ripe for a new Renaissance. She points to the flourishing of ateliers (traditional art workshops) that offer instruction in realist art and teach artistic techniques in a traditional manner.

For example, the Art Renewal Center (ARC) is one resource to find ateliers that teach representation art. Among other offerings, the ARC vets schools and instructors. However, Schmalstieg Barrett says, “There is a gap between what is taught in ateliers and what is needed to be a sacred artist; efforts are being made at St. Edmund’s Sacred Art Institute and other private studios to fill that void.”

Schmalstieg Barrett teaches devotional painting classes at St. Edmund’s Sacred Art Institute. Her latest class is a Eucharistic Still Life Painting Workshop, exploring the theology and techniques within 17th-century Altar Niche paintings. The goal is for students to create a copy of a master painting.

Pontifex University, an accredited online program that partners with St. Edmund’s and other workshops, also aims to fill the void. At St. Edmund’s, students can learn traditional iconography, illumination, calligraphy, stained glass, painting and drawing, etc. and get credits towards a Master in Sacred Arts through Pontifex.

The Catholic Art Institute is another resource that provides a community of Catholic creatives. Their mission is to revitalize Catholic visual arts and offer networking and educational opportunities. With the Catholic Art Institute and the other resources above, there are more opportunities than ever for artists to learn about sacred art and improve their craft to glorify God.

A Major Barrier for Sacred Artists

However, one significant barrier for sacred artists is funding. During the Renaissance, popes and patrons financially supported artists like Michelangelo. Today, creating religious art does not provide a stable living. Many artists teach or have other jobs to fill the gap.

“The reality is that there is more financial stability for an artist working in the secular sphere than one devoted to creating sacred art,” Schmalstieg Barrett says. “There are grants and fellowships to support work that expresses every fad of thought, but none to support serious Catholic ideas in the visual arts.”

Artists also need parish priests and bishops to avoid settling for manufactured prints. Instead, they should commission an original painting or a master copy by a sacred artist.

“Even if the space is well composed, the art is as stale as listening to the recording of sacred music rather than being in the presence of a living choir,” she explains.

It’s also crucial that Catholics support the education of artists. Artists determine the culture.

“Many people approach the culture as a war, not recognizing the need to actually support the culture makers,” she points out.

She adds, “For there to truly be a Renaissance, we need individual patrons and patronage institutions who will take the responsibility of supporting artists seriously.”

The Noble Mission of Artists

In 2008, addressing the clergy of Bolzano-Bressanone, Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI said, “Art and the saints are the greatest apologetic for our faith.” Like Pope St. John Paul II, Benedict XVI reminds us of sacred artists’ importance and mission: to masterfully make visible the invisible.

It’s a sign of hope that there’s a resurgence of artists who desire to improve their craft to create exceptional sacred art.

Tune in next week for Part II of this article, where we’ll share the stories of the four sacred artists interviewed in Part I!

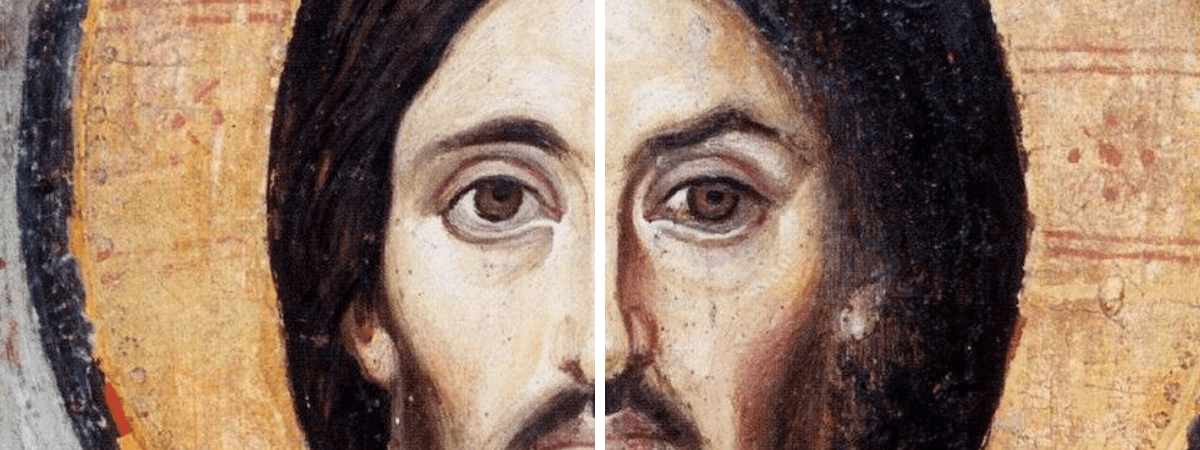

Featured image by Rachel Shrader shows an icon at St. Michael’s Abbey by Heritage Liturgical.