In this Lenten period of self-denial and bearing one’s cross, the cold ground and bare trees of the late winter season echo Holy Mother Church’s requests to embrace hunger and do without some of the more sumptuous bounties that bedeck our dinner plates—namely, to do without meat on certain days.

But why do Catholics abstain from meat, particularly on Fridays?

Why Catholics Fast (and Abstain from Certain Food Items)

While fasting is often accompanied by abstinence, especially during the Lenten season, the distinction between the two remains an important one.

Fasting, derived from the Anglo-Saxon term faest, meaning “firm” or “fixed,” refers to reducing or even completely refraining from all food for a certain amount of time.

Abstinence, on the other hand, stems from the Latin words “ab” and “tenere” which mean “to withhold” and most often pertains to giving up a specific type of food—in this case, meat.

The custom of going without meat is not strictly a Catholic one, but it has been recognized for generations as a beneficial practice adopted by believers and non-believers alike. Faithful Buddhists, Hindus, Jews, and Muslims all restrict meat in their diets to varying degrees and for different reasons according to their creeds. In the secular world, too, numerous restaurants offer special menus featuring Meatless Mondays to encourage personal and “environmental health.”

So, why do we do it?

For Catholics, this practice can be traced all the way back to Genesis. Once God had brought all of Creation into existence, filled it with life, and prepared the Garden of Eden, He made Man.

And the Lord God took man, and put him into the paradise of pleasure, to dress it, and to keep it. And he commanded him, saying: Of every tree of paradise thou shalt eat: But of the tree of knowledge of good and evil, thou shalt not eat. For in what day soever thou shalt eat of it, thou shalt die the death.

God’s first command to the first human being was one of abstinence!

Admittedly it did not concern the sacrifice of flesh, but that would come later.

Why Catholics Give Up Meat…

The fact is that doing without a certain food is perhaps the most ancient ritual of the human race and one which proved immeasurably disastrous to us when broken. Not only did our first parents physically “die the death”, but we are doomed to follow in their footsteps in addition to being in peril of spiritual death.

Yet it was because the Word was made flesh to suffer and “die the death” Himself on our behalf that He procured for us eternal life.

Christ offered up His flesh on Good Friday in the truest humility to atone for the pride of man. While man disobeyed God in order to avoid reliance on Him, Christ’s sacrifice only further illustrates our utter dependence on our Creator.

Similarly paradoxical, Jesus suffered His Passion at the mercy of man, and thereby showed us the greatest act of mercy through His sufferings.

In any event, man is impossibly beholden to God; first because of our transgressions against Him, and second because He redeems us anyway in the ultimate act of love.

However, in order to grow closer to Him, action is still required on our part. We may never achieve perfection, pay the debt we owe, or satisfy Divine Justice for all the hurt we have caused, but we can still die trying.

The Magisterium, Sacred Tradition, and Holy Scripture all indicate that it is most fitting that we fast and abstain in order to satisfy—if only in part—the debt we owe. Our payment is an act of justice, but doing penance of our own free will is an act of love in return. In either case, in order to assist the faithful in their efforts to grow closer to our Savior and reach the garden of eternal Paradise, The Holy Catholic Church has appointed the Fridays of Lent to be days of fast and abstinence.

Outside of Lent, Fridays are days designated for abstinence alone. (The Church never did away with sacrifices on Fridays, which many Catholics misunderstand.)

By giving up the consumption of flesh-meat, we offer up a worthy atonement—not only in commemoration of Christ’s ultimate sacrifice, but also so that we may (out of reverence) mirror his offering: we give up flesh for Him every Friday because He gave up His Flesh for us on Good Friday.

Thus, during the season of Lent, when we call to mind the sufferings of Our Lord more closely, it is only natural that we place more emphasis on this practice of reparation.

A History of Lent and Its Penances

Was this always the case in the Church? While the tradition of abstaining appears to trace its origins all the way back to the first Apostles, the exact standards varied greatly in early Christianity.

Even the period of Lent was not set in its current form until Christianity was legally permitted by the Roman Empire, and after the council of Nicaea took place in 325 A.D.

Even then it was not regularized until the papacy of Gregory the Great in 590–604 A.D.

In an effort to match the season of penance with the days that Christ spent in the desert, forty days had been set aside starting on Quadragesima Sunday, now known as the First Sunday of Lent.

However, since Sundays are permitted to be days of reprieve from the week’s mortifications, the days of attrition numbered only thirty-six.

Pope Gregory I is credited with adding the four extra days and marking the beginning of Lent on Ash Wednesday. He also supported the decision to ban the consumption of meat from all warm-blooded land animals and birds.

Yet the rules of abstinence did not end there, as he also decreed that the faithful also abstain from “flesh meat and from all things that come from flesh, as milk, cheese, eggs.” This included butter, broth, and meat sauces like gravy, all of which were often referred to as “white meats.”

These standards lasted a thousand years and traditions abound from Catholics forming their liturgical lives around them. The day before Ash Wednesday is known by many names: Shrove Tuesday, Mardi Gras, Carnival, and others.

You may be familiar, for example, with the custom of eating pancakes on Fat Tuesday. This practice was a direct result of Pope Gregory’s exhortation as the common folk made an effort to get rid of any extra “white meats” prior to Ash Wednesday. Pancakes include a collection of milk foods and, therefore, provided a perfect way to merrily dispose of them before Lent set in. The day came to be known as Carnival, stemming from the Latin words “farewell to flesh.”

After the pancakes disappeared, Ash Wednesday and the following fast days saw the arrival of the pretzel, a common Lenten commodity which traditionally contains no animal products. Roman Christians made a cord of bread and folded the ends of the dough together to imitate hands folded in prayer as an edible reminder of the season’s priorities.

While early Catholics exhibited great resourcefulness and ingenuity in preparing meals for the season, they weren’t wimps when it came to depriving themselves. Until the 8th century, it was not uncommon for the faithful to follow a black fast during Lent which meant either no food or only one meal was consumed (usually just bread and vegetables) for the day with a little water.

These fasts were most often observed on Ash Wednesday and Good Friday, but for those who were able, at least every Wednesday and Friday of Lent was lived this way.

Over the years, the Church relaxed this austerity—especially for laborers and mothers—and gradually introduced the dispensations which allow an extra meal, the re-introduction of white meats, and finally permission to eat flesh meats on the weekdays of Lent with the important exceptions of Ash Wednesday and Good Friday.

More recently, the practice of giving up something other than food has become common and the giving of alms is strongly encouraged as a worthy substitute.

Although other forms of penance have become popular and permissible, abstinence from flesh meat is still considered an essential part of spiritual preparation for holy days.

Before the Second Vatican Council, there were numerous days of abstinence outside of Lent: Ember days, Rogation days, Advent, and the vigils of Christmas, Pentecost, Assumption, and All Saints.

Eventually, these too were disposed of. Ash Wednesday and Good Friday remain the only obligatory days of abstinence. The Code of Canon Law currently states that

Abstinence from meat, or from some other food as determined by the Episcopal Conference, is to be observed on all Fridays, unless a solemnity should fall on a Friday. Abstinence and fasting are to be observed on Ash Wednesday and Good Friday.

Can. 1251

Today the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops states the rules of abstinence as:

On Ash Wednesday, Good Friday, and all Fridays of Lent: Everyone of age 14 and up must abstain from consuming meat and everyone of age 18 to 59 must fast, unless exempt due to usually a medical reason…Those that are excused from fast and abstinence outside the age limits include the physically or mentally ill including individuals suffering from chronic illnesses such as diabetes. Also excluded are pregnant or nursing women. In all cases, common sense should prevail, and ill persons should not further jeopardize their health by fasting.

So, why was fish permitted, and were there other exceptions to eating meat?

Why Catholics Eat Fish—and Once Upon a Time, Beaver!

Fish, while considered a form of animal meat, are neither warm-blooded nor a land animal and provide plenty of protein to rich and poor alike.

This didn’t necessarily mean that Catholics could dine on seafood delicacies instead. Fish meat is rarely as rich as the flesh of land animals and, before seafood delicacies became so widely available, it was considered a simple food that provided adequate nourishment and maintained the penitential spirit.

As Christianity spread beyond Christendom, Rome permitted bishops to grant dispensations to their flocks based on local customs and social circumstances. In many cases, dispensations were granted either to allow the faithful to eat animals other than fish or to celebrate a great feast day.

One example in the 1600s found the French fur trappers in Canada hard-pressed to adhere to the Lenten diet since vegetables and grains were scarce during the severe northern winters. In addition, fish were often difficult to obtain.

Beaver, on the other hand, was plentiful and—after conferring with the authorities in Rome—the bishop of Quebec permitted beaver to be eaten during Lent and classified the animal as belonging to the fish family due to its aquatic habitat.

This classification later applied to muskrat in other parts of North America, capybara in South America, and more recently, alligator in the diocese of New Orleans. Grasshoppers, too, have been condoned, in imitation of the self-mortification of St. John the Baptist—doubtless with much enthusiasm.

Feasting in the Midst of Fasting

As strict as Holy Mother Church may appear in her efforts to promote penance and reparation, she is not relentless in her exercises as evidenced by Laetare Sunday. She encourages all to share in a spirit of rejoicing even in the midst of penitential observances, since suffering in Christ will not last forever.

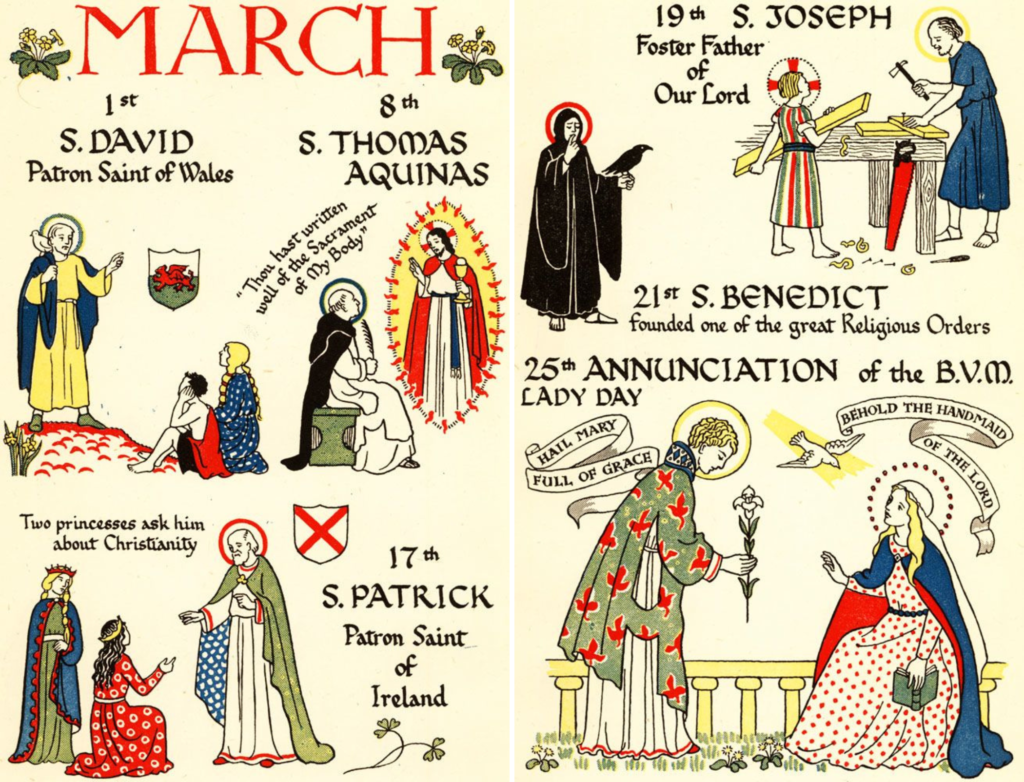

The Roman Catholic Church even allows small reprieves throughout Lent in the form of feast days. The solemnities of Saint Joseph (March 19th) and the Annunciation (March 25th) both supersede the ordinary observances and abstinence from meat is lifted for the day even if it falls on a Friday (other than Good Friday). In many parts of the world the Feast of Saint Patrick (March 17th) calls for similar dispensations and corned beef may be relished according to the permitted regions.

Our Lord did not give us specific commands about how to fast and abstain, but He did exhort us to be perfect. We also have Our Savior’s own example for inspiration. During Lent we are called to imitate His fast for forty days.

Both Jesus Christ and the Blessed Virgin Mary have emphasized the importance of penance in our lives so that we may make amends for sin and become worthy of our everlasting reward in Heaven. Had their guidance taken the form of commands, dispensations would not be possible and the practice of penance would have become a cold and impersonal one-size-fits-all directive.

Rather, Christ told us to pick up our cross and follow Him; in other words, we must first embrace the personal and individual sufferings that come our way because they are opportunities of grace sent by a God who loves us.

When we unite our pain and penance to the passion of our Redeemer, we will be able to rejoice with Him in His Resurrection and the promise of life everlasting that every Easter renews.

To emphasize the beautiful transformation of our souls that can happen in this holy season, we need look no further than the very name of the time itself: Lent. Derived from the Anglo-Saxon word lencten, it means “springtime.”

May you have a spiritual springtime this Lent, one that bursts forth with the flowers and fruits of divine grace.