Anyone brave or foolish enough to glance at today’s news headlines is doubtless overwhelmed by forecasts of war, invasion, and disease. Political strife and corruption seemingly abound in nearly every major country on earth and the state of the Church appears little better. The word that readily springs to mind is catastrophic. Our world, by all indications, is nearing a breaking point and any decent person hopes for the tides to change and for everything to turn out all right.

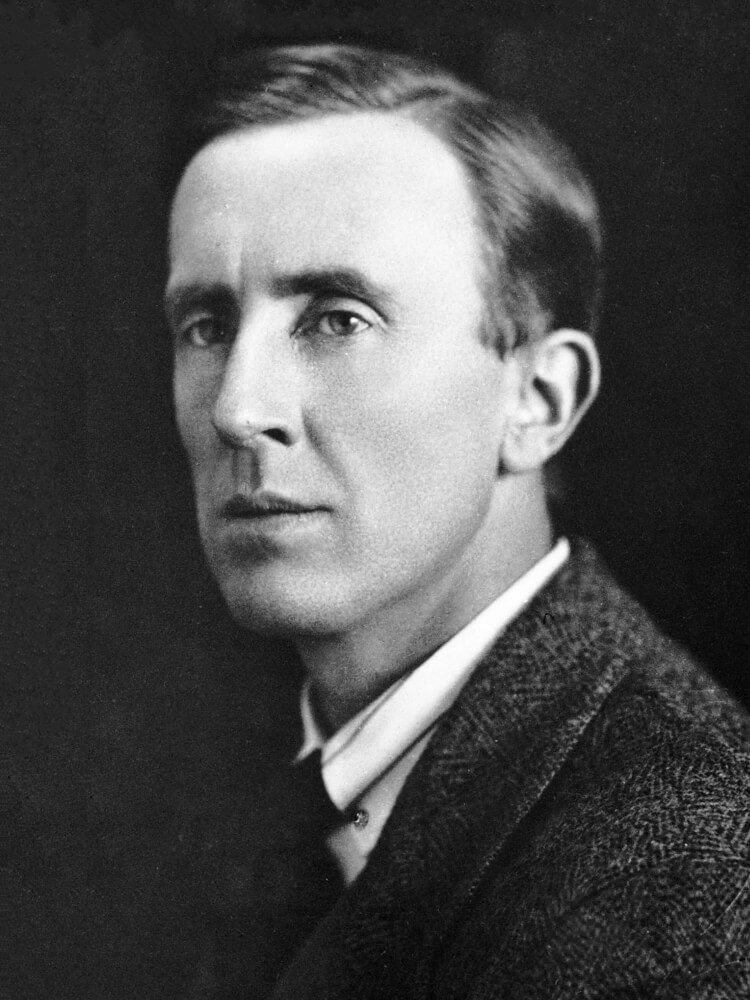

We want this story to have a happy ending. Every one of us hopes for a happy ending to our individual story and the greater tale we are part of. In order to better understand this innate human desire, one would be hard-pressed to find a finer guide than J.R.R. Tolkien.

The legacy of John Ronald Reuel Tolkien has more to do with deadly dragons, enchanted elves, and wandering wizards that embellish tales of high fantasy than a straightforward, practical, no-nonsense worldview. Yet, as strange as it may sound, this beloved author demonstrates that, with the help of the Catholic Faith, fiction can often provide a more effective approach to dealing with our messy world than cold, hard fact.

Tolkien’s philosophy does not reject the truth of the physical world, it merely looks at reality from a slightly different perspective: that of the storyteller. And in his stories, this master of tales provides what may be his greatest gift to the human race—his vision of Eucatastrophe.

What is Eucatastrophe?

In his essay On Fairy-Stories, the professor describes it thus:

But the ‘consolation’ of fairy-tales has another aspect than the imaginative satisfaction of ancient desires. Far more important is the Consolation of the Happy Ending…At least I would say that Tragedy is the true form of Drama, its highest function; but the opposite is true of Fairy-story. Since we do not appear to possess a word that expresses this opposite—I will call it Eucatastrophe. The eucatastrophic tale is the true form of fairy-tale, and its highest function.

The consolation of fairy-stories, the joy of the happy ending: or more correctly of the good catastrophe, the sudden joyous “turn”…In its fairy-tale—or otherworld—setting, it is a sudden and miraculous grace: never to be counted on to recur. It does not deny the existence of dyscatastrophe, of sorrow and failure: the possibility of these is necessary to the joy of deliverance; it denies (in the face of much evidence, if you will) universal final defeat and in so far is evangelium, giving a fleeting glimpse of Joy, Joy beyond the walls of the world, poignant as grief.

This idea of the happy ending was pivotal not only to Tolkien’s work as a whole, but also to its reception and popularity. Tolkien wrote thousands of pages detailing the tales of Middle-earth, but he was sparing in his use of Eucatastrophe, limiting it to only three direct instances in the legendarium.

“The Eagles Are Coming!”

In The Hobbit, Tolkien implemented Euchatastrophe at the Battle of the Five Armies, where Bilbo watches the armies of Elves, Men, and Dwarves cease fighting amongst themselves and unite against the common enemy of the Goblin army. However, the new alliance finds itself outmatched at the foot of the Lonely Mountain and their numbers begin to dwindle against the evil onslaught.

As Bilbo Baggins watches the bloody conflict, he realizes that defeat is imminent and that his friends will soon be killed. All will then be lost. Then, in the distance, the Hobbit spies aid from the clouds, unexpected and unannounced:

The clouds were torn by the wind, and a red sunset slashed the West. Seeing the sudden gleam in the gloom Bilbo looked round. He gave a great cry: he had seen a sight that made his heart leap, dark shapes small yet majestic against the distant glow. “The Eagles! The Eagles!” he shouted. “The Eagles are coming!”

J.R.R. Tolkien, The Hobbit

These Eagles are mighty creatures of immense size and power who serve as messengers from the divine realms of Tolkien’s world. Although the good forces are still outnumbered, the Eagles signal a change in fortunes and the goblins are eventually defeated.

The Return of the Eagles

In The Lord of the Rings, the Eagles again make an appearance at the uttermost end of need. The remaining forces of Gondor and Rohan unite and march on the black gates of Mordor, not expecting victory through strength of arms, but to buy time for the Ring-bearer to complete his quest and destroy the One Ring.

Another hobbit, this time Peregrin Took, finds himself on a different battlefield than Bilbo, but his encounter is a familiar echo of the first. Joining the fray, Pippin manages to kill a monstrous troll, but is incapacitated as the huge brute falls on the brave halfling, nearly smothering him.

“So it ends as I guessed it would,” his thought said, even as it fluttered away; and it laughed a little within him ere it fled, almost gay it seemed to be casting off at last all doubt and care and fear. And then even as it winged away into forgetfulness it heard voices, and they seemed to be crying in some forgotten world far above: “The Eagles are coming! The Eagles are coming!”

J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings (The Return of the King)

The Eagles appear just as the Men of the West are about to be crushed by Sauron’s forces and it is then that the Ring is at last destroyed.

Finally, in his posthumously published book, The Silmarillion, the Eagles are once again employed in a great and final battle. In the age preceding the events of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, the elven armies of Valinor come to the aid of what is to become Middle-earth and meet the dark lord Morgoth on the battlefield. After four decades of battle, the War of Wrath saw the forces of evil slowly driven back.

Yet the dark lord released his secret weapon, previously unseen in the preceding battles: an army of dragons. The elves suffer heavy casualties and are forced to retreat. In the face of defeat, the man Eärendil arrives in the skies like the morning star, helming a flying ship and bearing one of the great shining silmarils. He is accompanied by the great Eagles and together they slay the mightiest of the dragons and dispatch the rest. Morgoth is defeated and captured, leaving the world in peace, at least for a time.

Help From the Heavens

Despite the essential role the Eagles play in each story, Tolkien seems to have put little emphasis on the great birds, stating in Letter 210:

The Eagles are a dangerous ‘machine’. I have used them sparingly, and that is the absolute limit of their credibility or usefulness.

However, while not placing much importance on them as characters, he appears to have put a great deal of thought into them as symbols. Why might eagles accompany this sudden happy turn in the stories?

The Eucatastrophe in each of the books clearly shows help that comes from the heavens. The eagles are majestic birds of the skies with an air of authority. In The Silmarillion, the mighty birds accompany Manwё, lord of the air (a celestial being, similar to the Archangel Michael) who serves Illuvatar, the One who, for all intents and purposes, is God within the stories.

Manwё acts as the right hand of Illuvatar, fulfilling the will of the divine on Middle-earth. If the Eagles are participating in the story, then their appearance is an indication that something else is happening, a reminder that there are other forces at work in this world besides the will of evil. The Eagles symbolize the hand of Providence at work. They are Divine Intervention made visible.

When All Hope Has Faded…

Eucatastrophe is not escapism, nor is it a guarantee that everyone will live happily ever after. Throughout these legendary stories, there is great sacrifice, suffering, and loss. In The Hobbit, Bilbo mourns the deaths of three of his dwarven friends by the closing chapter. The Fellowship and its allies also experience the loss of several of their own in the quest to destroy the Ring. The Silmarillion too sees numerous characters fall, but this only goes to show the serious nature of the fight against evil—that hope, though ever persistent, remains fragile. Victory is never a certainty.

The fight is, rather, as Tolkien referred to it, the Long Defeat. The ongoing struggle mounts as time marches on, with the forces of good winning fewer and fewer victories, only delaying an inevitable decline as evil grows ever stronger.

This is always the state of things when Eucatastrophe takes place, when all is seemingly lost. The intervention only happens when the characters striving to preserve goodness have done all in their power to share and protect it. When these noble efforts are no longer enough to save what good is left in the world, then God intervenes and that sudden, indescribably happy turn reignites the smoldering embers of hope.

The final hope is that, in the end, ultimate Eucatastrophe will take place: evil will be vanquished forever, all hurts will be healed, and the world will be remade.

Fairy Fiction…or Fairy Fact?

This is a marvelous sentiment, but how useful is it for those of us living here in reality on planet Earth? One needn’t read works of fiction to be a good Catholic; after all, Fairy-Stories are one thing, but the history and time-tested traditions of the Faith are another.

Be that as it may, Tolkien did not see faith and creativity as mutually exclusive. He made sure that his work was rooted in the graces and virtues of his Faith, referring to his stories, specifically The Lord of the Rings, as a “fundamentally religious and Catholic work; unconsciously so at first, but consciously in the revision.” Tolkien was convinced that Christianity is the perfect bridge between the annals of history and the worlds of the imagination:

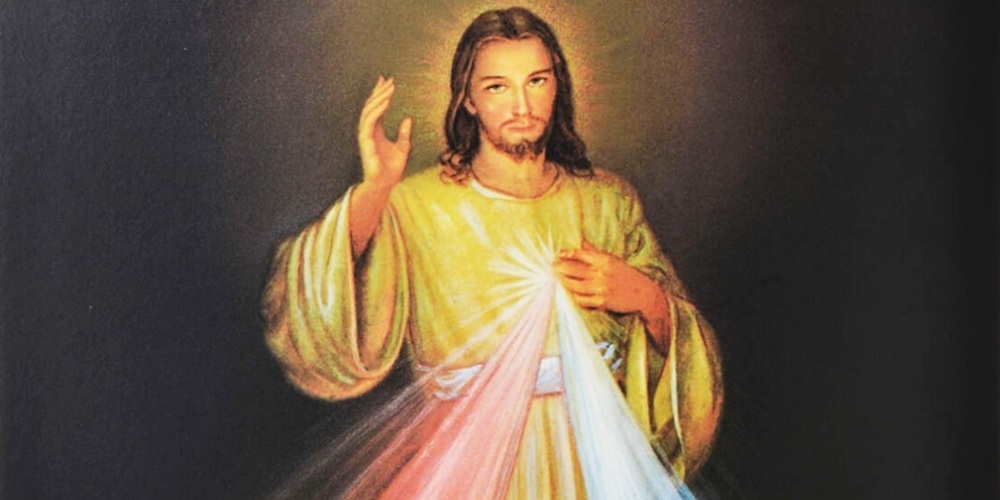

But this story has entered History and the primary world; the desire and aspiration of sub-creation has been raised to the fulfillment of Creation. The Birth of Christ is the Eucatastrophe of Man’s history. The Resurrection is the Eucatastrophe of the story of the Incarnation. This story begins and ends in joy. It has pre-eminently the ‘inner consistency of reality.’ There is no tale ever told that men would rather find was true, and none which so many skeptical men have accepted as true on its own merits. For the Art of it has the supremely convincing tone of Primary Art, that is, of Creation…Art has been verified. God is the Lord, of angels, and of men—and of elves. Legend and History have met and fused.

In 1944, Tolkien once again touched on Christianity as seen through the imagination in one of his letters (#89):

The Resurrection [of Christ] was the greatest ‘eucatastrophe’ possible in the greatest Fairy Story – and produces that essential emotion: Christian joy which produces tears because it is qualitatively so like sorrow, because it comes from those places where Joy and Sorrow are at one, reconciled, as selfishness and altruism are lost in Love. Of course I do not mean that the Gospels tell what is only a fairy-story; but I do mean very strongly that they do tell a fairy-story: the greatest. Man the storyteller would have to be redeemed in a manner consistent with his nature: by a moving story. But since the author of it is the supreme Artist and Author of Reality, this one was also made to Be, to be true on the Primary Plane.

Loving God with Our Whole…Imagination?

This may all be well and good, but do we have any indication that Christ wished for us to live for Him in this way or was Tolkien a little off his rocker?

Well, in Matthew 22:37, Our Lord gave us two great commandments. The first “…love the Lord thy God with thy whole heart, and with thy whole soul, and with thy whole mind.” How can we interpret loving the Lord “with your whole mind”?

In the ancient Greek texts, there are two words translated as “mind.” The first is dialogisimo, which refers to inner reflection, curiosity, or reasoning. It concerns the cognitive, analytical, and logical functions of the mind as we search for answers. The other word for “mind” is dianoia, meaning thought, perception, or imagination and in this instance is commonly understood to be what our Savior spoke of.

The imagination is the most creative of our faculties. In fact, it is what allows us creatures to imitate our Creator in His acts of creation. In the physical realm, we cannot build, design, paint, compose, or write without imagining. Spiritually, we would be unable to contemplate God and His works without imagination, as it is essential to sacred meditation, which enables us to know our Maker better. Imagination is a key way to understand the divine beyond purely tangible evidence and it helps our minds return to Christ in a supernatural way.

As if this commandment were not enough, there remains one more quiet, yet powerful instance in Scripture of knowing God through stories.

The Greatest Story Ever Told

As Christ stood trial before Pilate, the Roman prefect asked Christ if he was a king. Jesus responded:

“For this was I born, and for this came I into the world; that I should give testimony to the truth. Every one that is of the truth, heareth my voice.”

John 18:37

Although subtly, Our Blessed Lord alludes to the fact that the greatest story ever told is unfolding before the governor’s very eyes.

To give testimony is to relate a series of events to others and to stand by our word. Now if the Son of God is indeed the Truth, as He stated before, this passage, in a way, might be understood as Christ imparting the story of Himself to those who will listen: those who are of the truth hearing His voice.

This is both the summit of history, literally His Story, and of parable. It is both drama, due to the tragedy of Christ’s Passion and death, and Fairy-Story because of its impossibly happy ending. The grief of drama and the joyous turn of fantasy are reconciled through the Eucatastrophe of the Resurrection. God uses story to make Himself known to each of us, rendering His testimony timeless and accessible to all. With our imaginations, therefore, it is indeed possible to know, love, and serve our Creator better when we take to heart the best story of all: the Gospels.

Tolkien was right after all. Not only did he make unparalleled good use of the imaginative faculties with which he was gifted, but he employed them to turn his own mind back to the Divine. His legacy invites others to do the same.

The Eagles Are Coming

In his crafting of the adventures of Middle-earth, Tolkien not only gives credit to God, but also shares with us his testimony of the manner in which he sees the Creator. Surely it is no coincidence that when coining the word Eucatastrophe, with all its heavenly implications (Eu – “good” combined with katastrophe – “sudden turn”) there was another word that was at the heart of his inspiration: Eucharist (Eu – “good” and kharizesthai – “gracious offering”).

In the end, the fruits of J.R.R. Tolkien’s imagination teach us that all things are in God’s hands, a God Who never fails to bring the best good out of a bad situation. There may be much demanded of us if we are to walk in the light of God during times of darkness; our lives may be changed in the fight against evil or even lost, but the battle for goodness, truth, and beauty always merit that price. Virtue is truly something worth saving, and if we give our all in its defense, then heaven will assuredly intercede in God’s good time.

Until then, we aspire to fight the good fight and keep the Faith. We cling to the hope that one day we all can shout, “The Eagles! The Eagles are coming!”