The weather had been unseasonably benign in England during the first two weeks in September of last year. It was sunny, mostly dry, and quite warm. I’d honestly mispacked, bringing too much cold-weather attire. With England’s reputation for regular rain, I knew I’d been lucky.

Well, the two weeks were nearly up and my luck had run out. Familiar English rain made itself felt again as I ambled from the train station through the grey streets of Birmingham on my final day in the United Kingdom.

Birmingham is another one of those places that isn’t near the top of any leisure traveler’s list of must-see places in England (especially in the rain). It’s a northern industrial city stuck in the West Midlands—a landlocked flyover county in what I would venture to call a rather unhip chunk of Britain. It’s an important commercial and financial center, the second-largest city in England, but that’s about it.

If, however, you’ve followed my travels thus far, you’ve probably already guessed that I wasn’t spending the final hours of my trip in Birmingham just to see how many ways I could insult the place.

I was up to something.

I was, in fact, on my way in the rain to the most important Oratory in all of England: the Birmingham Oratory, the first Oratory in the Kingdom and the home of the great St. John Henry Newman himself.

Last But Not Least

I can’t remember whether it was the York Oratory or someone else who told me to go to Birmingham, but it was another one of those on-the-ground recommendations that entailed a last-minute, emailed interview request. It would be the last stop on my expedition before I turned my tracks homeward again.

As they had before, the Oratorians responded generously. A young seminarian, Brother Zachariah, was tasked with the job, but since I had to wait for him to get back from the seminary at 4 o’clock, I had plenty of time to explore the magnificent basilica church beforehand.

Mass was at 12:30, one of three Masses offered every weekday (they have no fewer than five Masses on Sunday and three on Saturday). As is normal with Oratories in this part of the world, they offer the liturgy in both English and Latin.

Ever since their establishment by St. Philip Neri in Rome, Oratorian communities have always been devoted to supremely beautiful liturgies and music, and Birmingham is certainly no exception. The High Latin Mass celebrated at 10:30 every Sunday morning must be a celestial experience.

The liturgical schedule is adorned with Benediction, Adoration, and devotions to the Oratorian saints throughout the week. It was Monday when I went—the day for devotions to St. Philip Neri. After Mass we lined up on the left side of the church, before the chapel of St. Philip, for a blessing with a relic of the revered founder of the Oratorians.

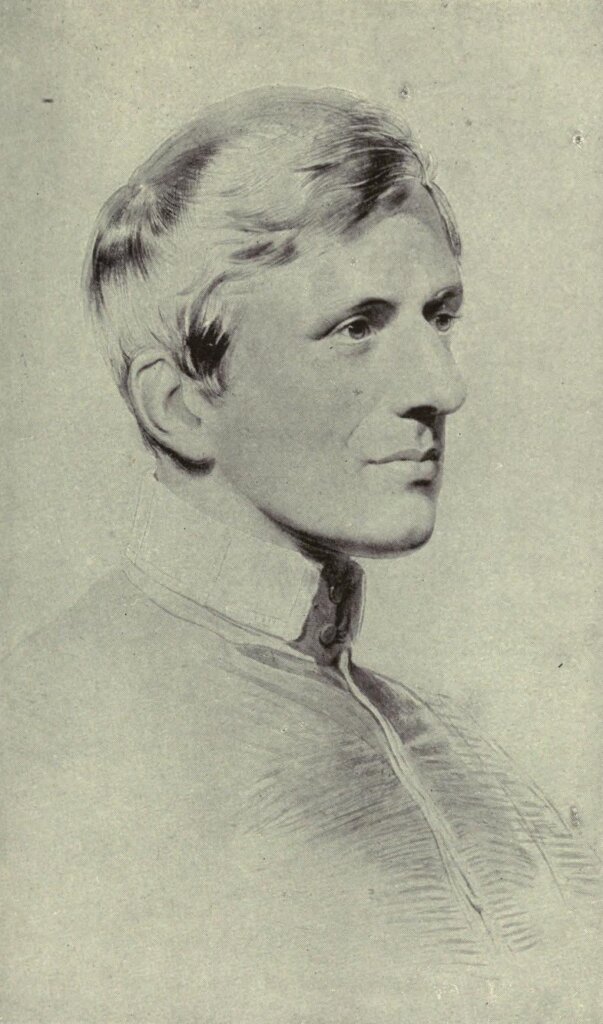

On the right side of the church is a larger chapel which was, in fact, the original church of the Oratory before the current one was built in the early 1900s. Now it is dedicated to Newman, who said Mass here regularly and whose portrait hangs above the fine alabaster high altar.

Around the chapel are portraits of various saints of importance to the community, including a seemingly-obscure beato named Blessed Dominic Barberi—obscure, that is, to American Catholics, but a beloved figure in English Catholicism.

For the Love of England

I thought I was nearly done with this article, then I read about Blessed Dominic—a Passionist of Newman’s time—showing up at Newman’s doorstep in the rain.

The Passionist Order is not very well known in the United States from what I’ve observed, but England has it as a literal shield upon her arm. More than once I noticed the Passionist shield—a black heart with the three nails of the Passion and the inscription “Jesu XPI Passio” (“the Passion of Jesus Christ”) engraved in a stained glass window or framed on a wall in an English church. (I tend to notice the Shield whenever I see it because of a longtime devotion to the Passionist saints).

Art credit: Jayarathina/CC BY-SA 4.0

The Congregation of the Passion being a small order to begin with, one might wonder why the English harbor such a collective devotion to it.

The reason is that England owes a lot to the Passionists.

St. Paul of the Cross, the founder of the Passionists, had an enduring love for England and prayed fervently for her conversion. He would never go there himself but Dominic, who was born 17 years after St. Paul’s death, was the answer to his prayers.

Blessed Dominic founded the first Passionist house in England in 1842. A companion in his labors was Fr. (now Venerable) Ignatius Spencer, a great-uncle of both Winston Churchill and Princess Diana.

It was this Blessed Dominic who, in 1845, arrived in Littlemore, a town outside of Oxford, to pay a visit to a semi-monastic group of scholars living there. This community was the sequel to the Oxford Movement, started by Newman and his friends at the illustrious university some years before. The Oxford Movement sought a renewal, a “second Reformation,” of the Church of England, which they saw as overly-attached to the secular powers.

The natural result of the investigations of the Oxford scholars was, of course, a return to Catholicism, and some of the Littlemore group were already Catholic. Newman too had made up his mind. The visit of Fr. Dominic offered him the chance to make good on this decision.

The Passionist priest was hardly unknown to these scholars. Some time before, Dominic had directly addressed the Oxford Movement, writing a letter to the “Gentlemen of Oxford,” answering their theological queries and assuring them of his prayers. This letter, along with Fr. Dominic’s personal dedication and holiness, had struck a deep chord with Newman and his friends that would bear great fruit later.

That night in 1845, the Passionist father came in from the rain (ha!) and, as he dried himself by the fire, Newman entered, knelt at his feet, and earnestly begged for admittance into the Church. Fr. Dominic heard his confession (which was so long it had to be continued the next day) and Newman attended Mass that Sunday in Oxford for the first time as a Catholic.

Needless to say, this caused an earthquake of the best kind in England and much rejoicing in Rome. The rest is history, and John Henry Newman is now both a saint of the Church and one of her great conversion stories.

Fr. Dominic died of a heart attack only four years after Newman’s conversion and is buried just north of our friends at St. Mary’s in Warrington in the town of St. Helens, along with Venerable Ignatius Spencer and Venerable Mary Prout, another English Passionist.

The Father of the Oratory

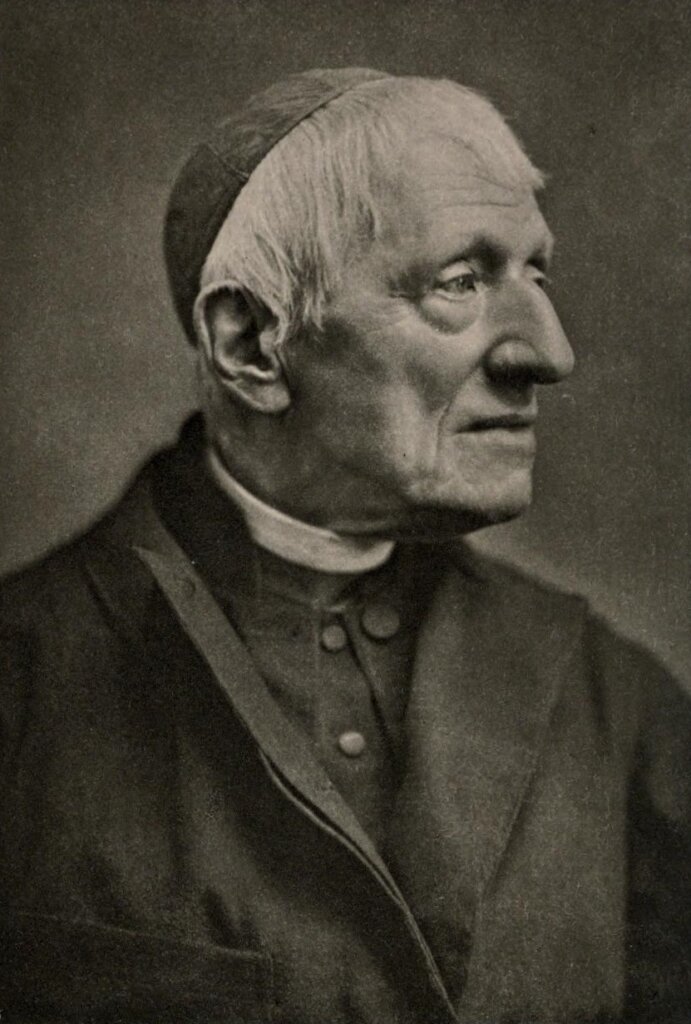

In Birmingham more than 170 years later, continuing what appeared to be a fine Passionist tradition of showing up on Newman’s doorstep in the rain, I sat in a room with a cup of tea in my lap at the veritable feet of the founder and Father of the Birmingham Oratory. Surrounding me were countless artifacts from his life.

Here was his cardinal attire and shoes, standing neatly in a display case, seeming as bright, red, and crisp as if he had worn them yesterday; here was his gold chalice; there was an hourglass and desk accessories; in another case were his rosary, manuscripts, and countless other relics.

Brother Zachariah sat nearby, recounting the intertwined history of the Oratory and its sainted founder with the familiarity of his own family story. It made sense that he would—after all, it was his family story. Oratorians, as we have seen, are more closely bound to their particular Oratory than most of us are to our own homes.

And one of the particular missions of this Oratory is to preserve the heritage of Newman, who is not only their own founder and Father (“Father” is the term for the superior of an Oratory), but the father of all English Oratories and an irreplaceable figure in English Catholicism.

The Oratory of St. Philip Neri—as the Birmingham Oratory is officially called—was the fruit of the time Newman spent in Rome after his conversion, exploring various religious orders to see where he would fit in. After finding his match in the Oratorian community, he founded the Birmingham Oratory with a few friends in 1848—the first foundation of the Congregation in England.

That country would turn out to be particularly fertile ground for the order, and now hosts four fully-fledged Oratories (London, Oxford, York, and Manchester) as well as one in formation (Bournemouth) and two in formation in the wider British Isles (Dublin, Ireland and Cardiff, Wales). (Note to self: there are so many more Oratories to explore. I really ought to go back soon…)

The Oratory was located in a few different places in Birmingham—including, amusingly, a converted gin distillery which still exists as the Church of St. Anne—before settling in 1852 in Edgbaston (pronounced “EDGE-bas-tun”), near the city center, where it resides today.

“The life of the Oratory, the mission of the Oratory here in Birmingham has been twofold through its history,” Brother Zachariah explained. “First of all, it’s been ministering to the parish that we have here, a large parish, a large, diverse parish. And that’s primarily our work, our mission. But then secondary to that is preserving the legacy, the patrimony of Newman. So we have his many letters, his books, his own library. And the Fathers [of the Oratory] have also, over the last century and a bit, tried to preserve his thought as well and everything that he left to us in his writings, in his theology. So Newman is still a very important part of our lives.”

Preserved within the Oratory walls is Newman’s own room, just as he left it. (It is normally accessible but was under construction at the time I was there.) The Fathers not only preserve all these things and offer them for the perusal of wandering American writers, but open them to the public to further devotion to the Cardinal and educate visitors about this vital figure in their city’s and country’s history.

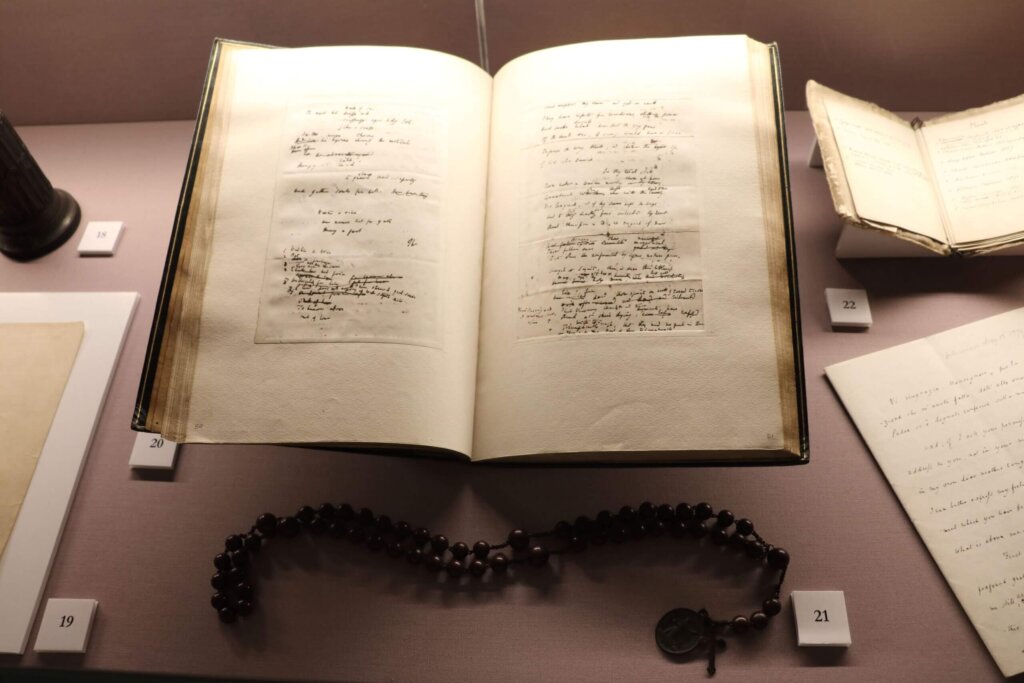

One particular artifact caught my attention in the museum. On display was the original manuscript of The Dream of Gerontius, Newman’s famous poem about Purgatory that, incidentally, Good Catholic had referenced in our then-recently-released series Purgatory: Cleansing Fire.

Excited by the find, I was given permission to photograph it. You can read more about The Dream of Gerontius in Day 25 of that series.

Right at Home

Between 800 and 1000 people come to Mass every Sunday at the Oratory. The parish covers territory on both sides of the Hagley Road, one of the main thoroughfares through the city. It contains some of its wealthiest and poorest areas, a demographic mix that is reflected, said Brother Zachariah, in the congregation they serve.

“And we have a large number of confessions here, so perhaps more significant than any other part of our pastoral ministry is our confessional ministry,” he explained. “So we find people travel from all parts of the city and beyond to come to confession here, and we have confessions available at two of our three public Masses every day, and at every Mass on Sunday. And so we often find our Fathers will be hearing dozens of confessions every Sunday.”

This aspect of the Oratory was in perfect keeping with the Oratories I had visited thus far. The consistent, daily availability of confession is an integral and intentional feature of these communities, a powerful magnet that draws both those seeking a consistent prayer and sacramental life and those contemplating a return to the sacraments. Whether you’re a saint, a sinner, or someone in between, nothing encourages you to drop into the confessional like having it right there on your doorstep every day.

While they have some other duties in the area, such as providing chaplains for nearby schools and prisons, Brother Zachariah emphasized that their pastoral work is centered around their own house, parish, and the people they serve within its walls.

“One of the things we try to be is at home,” he explained. They strive to be on location and available to people whenever they need them.

At home. I’ve explored this concept of the “parish as home” in previous articles in this series, and Birmingham provides yet another fine Oratorian example of this concept in action.

The Sanctification of the Laity

The Oratorians’ particular connection to the laity is another aspect of their charism that makes their institutions such a “home” for souls. As we explored in our first post on the Oratorians, St. Philip Neri founded the Oratory as a lay organization. The life of the Oratory is therefore uniquely designed to provide for the consistent spiritual formation and sustenance of lay people. It was made for them, you might say.

Photo courtesy of the Birmingham Oratory

When I asked what kind of activities brought the community together, Brother Zachariah answered:

“Well the center of any Oratory, its original core, which is the secular Oratory—so the gatherings of lay people for prayer in common. St. Philip founded the Oratory first of all as a lay institution, and only in time did it become the clerical, the priestly congregation that we now associate it with. But we have that secular Oratory, or Little Oratory, oratorium parvum, as the center of the life of the parish, I suppose, and with that there’s the men’s Oratory, which is the Little Oratory, we have the women’s Oratory, we’ve got a junior Oratory, and we’ve recently revived a youth Oratory for teenagers. So these are ways for the laity to come and to pray together, to follow the spiritual exercises that St. Philip gave us, the exercises of the Oratory. And those groups all have their own social activities and ways of recreation.”

I find this aspect of the Oratorians particularly unique and downright cool. Before that trip I had never before met a religious institution so firmly bound to the laity—that was both built from lay beginnings and has kept the laity as such an integral part of its life.

At home, with the lights on, the sacraments and spiritual support consistently available, with the laity built right into its life—the attraction of these Oratories for average lay people is undeniable.

A Great Place for Converts

Though his presence at the Oratory is as natural as if he’d been there all his life, Brother Zachariah is actually a fairly recent convert.

“The Oratory has always been a great place for converts,” he noted wisely. (You’ll recall the number of young converts the Fathers in York counted among their congregation.)

Brother Zachariah is a native son of Birmingham and grew up near the Oratory, but coming from a non-religious background, he did not know the place in his youth. He was drawn to the Faith while at university in York, following on some feelings in his teenage years that maybe there was something more out there than what he had known thus far.

“And then it was, I think, grace working through a variety of means,” he said of his conversion. “I was drawn to the beauty of worship, of the music and art of the Church, and then on another level entirely, to the coherence of Catholic thought.

“But then, and perhaps mainly by the example of the Catholics I met, [I saw] that this was the place where one saw people living a life that seemed to be in some way reflective of what they believed. But all of those things on different levels, I think, formed links in the chain.”

He was baptized in York then got to know the Oratory upon his return to Birmingham. His religious vocation followed soon after, happening like all true Oratorian vocations do: he just felt like he belonged there, quasi natus—as if born into it, as the Oratorians would say.

To Love to Be Unknown: The Strange Case of Newman’s Tomb

Hours, maybe days, had passed after my visit when I realized something: I hadn’t visited Cardinal Newman’s tomb.

Feeling rather silly about it, I rummaged around for information on where he was buried. The internet told me it was at the Oratory. But where? I’d been in the main church and the large side chapel dedicated to Newman. I hadn’t seen anything that I’d recognized as the tomb of a saint.

How could I have missed it? (And how is it that I didn’t even think of it?)

I felt a little better when I found out that the location of Newman’s body was not a straightforward question.

After his death in 1890, Cardinal Newman was buried in Rednal, an area outside the city with chronically damp ground. He was buried there by his own wishes, in a simple wooden casket that for sure would not stand up to the elements, complete with a layer of moss to hasten decomposition.

In 2008, an attempt was made to exhume his body with the intention of moving it to the Oratory prior to his anticipated beatification. However, the exhumers found…nothing.

Not a trace of the Cardinal’s body remained. It had totally decomposed, along with most of the casket. Only the metal handles and some other metal ornamentations survived, along with a Latin-inscribed plaque:

The Most Eminent and Most Reverend John Henry Newman Cardinal Deacon of St George in Velabro Died 11 August 1890 RIP.

The clever cardinal had outfoxed us all. He couldn’t always stop people from adulating him during his life, but he could do his best to prevent it after his death. I wonder how many secret smiles and quiet laughter echoed through the halls of England’s Oratories when they found out what their saintly and wily founder had done.

The idea of deliberately decomposing ourselves may seem odd to us, but it probably made sense to any follower of St. Philip Neri. After all, one of his sayings that has become a maxim of the Oratorians is amare nesciri—to love to be unknown.

Brother Zachariah had referenced this when I had spoken with mild embarrassment of my own ignorance regarding the incredible treasures hidden within the Birmingham Oratory.

“No, it’s wonderful,” he said, viewing such a discovery as a positive good. He noted that even among the 40 people to whom he had given a tour during the recent Heritage Open Days (a government initiative that invites people to discover their local historical and cultural landmarks), none knew of the Oratory.

“But that’s almost by design,” he said, “because we don’t like to publicize ourselves. We have the ideal that St. Philip gave us of loving to be unknown, amare nesciri. So we like to be discovered. We don’t publish ourselves very much.”

Famous in life and death, with his memory always cherished by the Oratorian sons he left behind him, Cardinal John Henry Newman will never be unknown. But his final act of humility—and the love of obscurity that he inherited from St. Philip and passed on to his followers—is certainly a lesson to all of us who’ve ever hungered after recognition.

So, the final answer to the question of Cardinal Newman’s tomb is that there isn’t one. A small, elevated, casket-like reliquary stands in his shrine chapel, which contains a lock of his hair and some soil from the grave, with the handles of the Rednal casket fastened to the outside. A small piece of bone from the grave, taken to be his, once was there, but even that was stolen a few years ago.

I saw the small casket in the shrine, but for some reason I don’t remember even thinking that something important might be in it when I was observing it.

I like to think Cardinal Newman was watching, perfectly content with my obliviousness. He probably was happy about the rain, too. +