Something moves in the twilight. In the chilly autumn evening, an armored figure mounted on a pale charger patiently leads a small army. However, the little band does not brandish swords or spears, but twinkling lanterns. Instead of fierce war-cries, the air is filled with the tiny voices of children’s song.

The sunlight fast is dwindling.

My little lamp needs kindling.

Its beam shines far in darkest night,

Dear lantern, guard me with your light.

It is the lantern walk of Martinmas and, incredible as it may seem, this curious procession and the customs that accompany it have had a profound influence on the course of our country’s history. But what story lies behind this quaint custom, who was the man that started it all, and how could it have any bearing on the formation of the United States of America?

The Roman Soldier Who Became a Saint

November 11th marks the feast day of St. Martin of Tours, a man remembered as a peaceful warrior, a popular hermit, and a zealous bishop. Martin was born during the reign of Constantine in Savaria, Pannonia, today known as Hungary, around 316 A.D. Yet this famous man of God was not born a Christian.

His father had distinguished himself in the army of Rome and had retired at the respectable rank of tribune. Martin was struck by the goodness, truth, and beauty of the Faith as a boy and became a catechumen. Unfortunately, his parents prevented his baptism and once he was fifteen, pressed him into military service. He soon became an officer in the cavalry and it is believed that he served as part of the emperor’s own elite bodyguard at one point while stationed in Milan, Italy.

Even in military surroundings, Martin held fast to his creed. He showed exceptional fairness to his subordinates, was extraordinarily generous to all he met, and displayed the greatest courage against those who wished him harm. In short, he lived a life of virtue—even before his baptism.

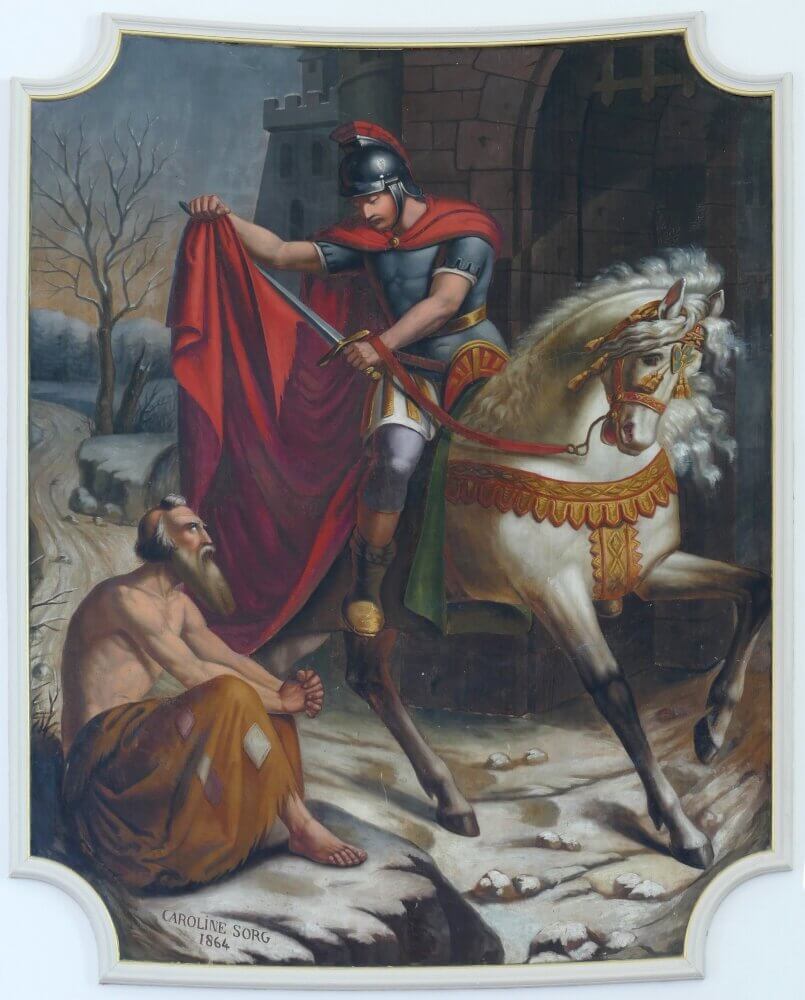

It was during this time that the story he is best remembered for took place. According to the hagiographer, Sulpicius Severus, Martin was approaching the city gates of Amiens in Gaul, not far from Tours, France, in the midst of winter. There he encountered a shivering beggar. Seeing that none had pitied the vagabond in his miserable state, the holy soldier was moved to even greater pity for his fellow-man. Having given away any money on his person and even some of his own dispensable garments, the soldier had little left to give. But give he did, for he dismounted, unsheathed his gladius, and rent his own military cloak precisely in two, handing one half to the poor man.

Photo credit: Ralph Hammann/CC BY-SA 4.0

Roman capes were substantial garments. Measuring at least a full body’s length, they were made of thick warm wool and naturally infused with a light layer of oil to shed water. A Roman soldier would keep his cape on his person at all times, ensuring that he had a weatherproof wrap to insulate himself during frosty night encampments.

Cynics might criticize the holy man’s decision to part with only half of his cozy cape instead of showing more benevolence and giving the beggar the entire thing, but there appears to be a very reasonable answer to this: Martin gave what he could according to his state in life. He was a soldier carrying out orders; as a man subject to another’s authority, his famous act ensured that he would remain capable of fulfilling the responsibilities expected of him while still practicing a rare form of generosity.

A soldier’s cloak was the single article allowed as a personal garment while in the service. Armor, weapons, and any other equipment were property of the empire and would often be reissued for years to different soldiers. Therefore, Martin could not justly sell his other attire and supplies. He also took seriously the army’s expectation that he be a responsible and obedient subordinate. Thus, by keeping half of his own cloak, he could preserve his own life in the service of others.

Furthermore, the saintly soldier’s deed stood as a public recognition of the dignity of the unfortunate man in his path, which he demonstrated by sharing exactly half of all he owned. This symbolized Martin’s firm belief that the beggar’s life had equal value to his own. So, while this account splendidly illustrates the spirit of generosity, it also teaches the application of true prudence.

That night, the cavalryman saw in a dream Christ Himself surrounded by angels and clad in the shorn crimson mantle. When questioned by the attending cherubs as to why he wore half a cloak, Our Lord declared: “Martin, still only a catechumen, was the one who clothed me!”

Thereafter, Martin redoubled his efforts to join the Christian Faith and was soon baptized. While he remained in the army for a few years after he was received into the Church, he was determined to leave once the anti-Christian emperor Julian the Apostate assumed power. It was also at this time that the Roman provinces witnessed renewed wars with barbarian invaders. Martin would not accept compensation from the unjust Caesar and refused to engage in any further campaigns, telling him: “I have served you as a soldier; now let me serve Christ. Give the bounty to those who are going to fight. But I am a soldier of Christ and it is not lawful for me to fight.”

He was consequently imprisoned and even volunteered at one point to remain with his men on the front lines unarmed. His commanding officers expressed willingness to grant his request, but before the two armies could clash on the battlefield, a peace was negotiated and Martin’s life was spared. After some time and many difficulties, Martin was at last released from the army.

Once Martin left military life behind, he became a disciple of the future saint, Bishop Hilary of Poitiers, who ordained him a deacon and subsequently an exorcist. Martin labored energetically to spread the Faith and combat the heresies of Arianism. Although he sought solitude as a hermit, Martin’s life never remained quiet for long. He established many parishes and monasteries, preached wherever he went, and converted many souls, including his own mother.

Later becoming the bishop of Tours, Martin performed many miracles, such as raising the dead back to life on three separate occasions. On another occasion, Martin deliberately stood in the path of a sacred pagan tree that was being felled to prove that God would not allow the old heathen tree to overcome His faithful servant. The tree fell hard beside him after swerving mid-air.

Martin spent the rest of his life ministering to his flock, which forever endeared him to the faithful. Upon his death on the 11th day of November, 397 A.D., commemorations were held to mark the life of one who brought so many closer to God.

The Customs of Martinmas

While his memory has enjoyed immense popularity in France, the country where he ministered, it is the Germanic regions in which he was born that have preserved the St. Martin’s Day customs and traditions that we cherish today.

The aforementioned procession of children with lanterns is one such practice and is known by the names lantern walk, lantern fest, or laternelaufen in Germany, where the memorial is practiced with the greatest vigor. While its origins remain a mystery, the symbolism emanating from the lantern walk shares as vivid an assortment of possibilities as the homemade lanterns on display.

Photo credit: Bundesarchiv, Bild 194-0273-38 / Lachmann, Hans / CC-BY-SA 3.0

One can easily recognize the simple lamps as the light of Christian charity bringing warmth to those in need. Perhaps they epitomize the flame of the Gospel setting the world afire with the love of God. Maybe they embody the divine spark of the Faith illuminating truth to others. It is most fitting, then, that this festival of light be held just before the impending darkness of winter.

The rustic glowing vessels come in all shapes and sizes. Some may be glass jars swaddled with brightly colored shreds of paper like stained glass. Others may be hollowed gourds with star-carved windows. Many are paper orbs adorned with the fiery leaves of autumn. In every case, the candle-bearers raise up their voices in song and petition the man of the hour to intercede for them as they celebrate his celestial status.

As one may guess, the horseman leading the cavalcade is meant to be the holy Martin. Customarily, the merry gathering travels throughout the town before concluding the ceremony before a great crackling bonfire. Treats are dispensed, toasts are proposed, and young and old alike find merriment in shared company. It is a custom that emphasizes the fact that paying tribute to the heavenly figures may be done with childlike simplicity and humble means just as effectively as with marble-hewn sculptures and golden regalia. The magical lantern walk offers a testament to the ways of Divine Providence, for it illumines the mysterious truth that grace builds on nature, and that the Creator of all things is eager to work with us through His creation.

This was only one of the ways in which St. Martin’s feast was observed. Throughout most of medieval Europe, Martinmas functioned not only as a supernatural celebration, but also as a natural one. Spiritually, the occasion concluded the Allhallowtide season, earning it the title of “Old Halloween,” since it occurred after the All Souls’ Day octave and initiated the season known as “St. Martin’s Lent” that lasted until Christmas Day. Physically, it capped off the end of harvest time and signaled the start of the winter months. This autumnal festival was an occasion for merrymaking and feasting. The first batches of wine from the summer’s bounty were opened (christened “St. Martin’s wine”) and the fattest livestock were prepared for the tables.

It seems that, in the Middle Ages, central and northern Europe were particularly fond of serving roast goose as the main dish. Legend has it that when Martin was attempting to live out his days as a hermit, the local populace became so enamored with his charism that when their own bishop died, they intended to make the holy monk his successor—by force if necessary. When they went to retrieve him, Martin hid in a goose shed hoping to avoid detection; however, the waterfowl caused such a stir with their honking that he was soon found out and carried to the bishop’s quarters.

Once he was officially appointed a prince of the Church, his attendees asked if he had any requests for his first dinner as bishop. He humorously replied that he only wished for one of the birds who gave him away to be roasted and set before him. The story stuck and the unfortunate bird quickly became the traditional centerpiece for this momentous feast in Christendom.

With or without goose, Martinmas grew into a grand communal event where the participants placed particular emphasis on gratitude for the gifts that God had given them. It was a day of thanksgiving.

Martinmas, the Puritans, and the Origins of Thanksgiving

Enter the future settlers of the United States—the pilgrims.

When the Puritans broke off from the Church of England, they withdrew to start a community of their own, free from the religious regulations of the Anglicans. Many believed that the Protestantism of Henry VIII and his successors wasn’t thorough enough in its efforts to rid itself of Catholic influences.

While many had strong ties to their native England, the Puritan populace eventually endeavored to start a colony in the Netherlands. In about 1607, they found a new home as they arrived in Leiden, Holland. There, most of them would remain until 1620.

Life with the Dutch provided opportunities for a good life, but the Germanic culture proved difficult for the Englishmen to assimilate. They were far from the friends, family, and home that they once knew, surrounded by strange people in a strange land. The Puritans’ children began to integrate into the Dutch culture better than their parents had.

Eventually, the community needed a place to call their own, and the shores of the New World promised a new beginning. In December of 1620, the Mayflower reached its American destination at Plymouth Rock, Massachusetts.

After a year of intense struggle, innumerable hardships, and irreplaceable loss, the Pilgrim colony dedicated a time of giving thanks for their new establishment in the fall of 1621.

However, this was not a Puritan tradition, but a Catholic one.

In the years preceding the Puritan movement, Martin Luther sent shockwaves through the world when he publicly protested the teachings of Catholicism. Many of his ideas took hold in Europe and his new ideology attempted to root out any feast day that wasn’t dedicated solely to Christ. The holy days of the saints were the first to go, but that was easier said than done. Many nations obeyed the Lutherine edict; others, like the Netherlands, weren’t as quick to dispense with the beloved celebrations of their heritage. Doubtless, it was during their sojourn in the Dutch countryside that the Puritans witnessed firsthand the ceremonies and local traditions of the yearly thanksgiving known as Martinmas, traditions that they would later bring to our country—and the rest is history.

The similarities between the two feasts of Martinmas and our own Thanksgiving are obvious: in both cases, a sizzling bird sits in the center of the dinner table encircled by the sumptuous abundance of the harvest with the virtue of gratitude enshrined as the order of the day. It is a marvelous thing, a mysterious thread in the grand tapestry of God’s design, that those who most severely tried to rid themselves of any Catholic vestiges ended up preserving a practice that was planted, cultivated, and shared by the One True Faith.

The Martinmas lantern walk is surely a grand old custom that deserves to be revived in every American parish and town, especially in these ever-darkening times when gloom and despair lurk all too close in the shadows, impatient for the fragile and flickering light of the Faith to be extinguished. May that light confound the darkness and grow, sparking new flames of the caliber of St. Martin of Tours, who truly lived the charge of our Savior: “So let your light shine before men that they may see your good works and glorify your Father who is in heaven.”

Until that day arrives where such armies of light are a common sight, we should all remember, while carving our turkeys this year, that we have a saintly Roman soldier to thank for the first public holiday enjoyed by the United States of America. Let us remember the roots that link our popular Thanksgiving Day with the Christendom of ages past, for the history of this holiday sheds light on the spirit of the Christian life: a life filled with light that grows when it is shared, a life spent giving thanks and glory to the God Who made all good things.

Did you know about this amazing connection between Martinmas and our country’s history?

Do you have particular traditions with which you celebrate the feast of your favorite saint?

Let us know in the comments below!

To learn more about how shared meals deepen our faith and why we celebrate the feasts of the saints, check out our new series, The Heavenly Table.