What is it about monasteries that fascinates us so much and draws us in?

If you’ve ever been to a flourishing monastery, convent, or friary, you probably know what I mean. They are innately attractive. There’s an aura about them that just pulls you in, like a gravitational field.

Maybe it’s the beautiful art, music, and liturgy so often found in monastic settings. Maybe it’s the mysterious and effusive joy of those who have found their happiness in completely detaching themselves from the world and all its evanescent pleasures. (I think even those of us who are called to the lay state are a little jealous of this joy.)

Maybe it’s the feeling of shelter that these houses of God bring to us pilgrims and the refreshment that they give us. Maybe it’s the community with fellow-pilgrims that such wayside shrines tend to gather about themselves. Maybe it’s the hospitable welcome we always get at these places, no matter who we are.

I—and anyone else who has wandered into the aura of a monastery—would rather just sit outside the door of one of these places than visit so many other “exciting” places on earth, or do any of a thousand more exciting things that the world has to offer.

St. Michael’s Norbertine Abbey in Silverado, California, is one such place.

As I promised you in my last article on California, it’s our next stop in our ongoing exploration of the oases of Catholicism in the Golden State.

The Story of the Order of Premonstratensians

The Norbertine Order is really old.

They sprang up in the 12th century at a time when the clergy of the Catholic Church were badly in need of reform and revitalization. Their founder, St. Norbert of Xanten in Germany, was a part of the problem early in his life.

Norbert was born into a noble family and became a subdeacon in his youth. But he was far from an ideal cleric—he, like so many other men of the cloth at the time, led a life of worldliness enabled by his wealth and his high-level appointments to the court of the Bishop of Magdeburg and then of Henry V, the Emperor of Germany.

But one day, everything in Norbert’s life was upturned in a literal flash.

Some of us long for a bolt of lightning from heaven to help us decide between paths in life. For Norbert, this was the painful reality.

As he rode along on his horse one day, a lighting bolt struck the ground right in front of him. This spooked the unfortunate beast, which threw its rider to the ground. Norbert lay there stunned for a time, and when he arose, he was probably hurting on the outside, but inside, he was healed.

The new Norbert first set about doing penance for his former life and spending time in prayer and self-reflection to discern the path forward. After becoming a priest, Norbert founded the order that bears his name in the marshy valley of Prémontré with several disciples.

The new order was called the Canons of Prémontré, the Premonstratensians, or simply the Norbertines, who took their rule from that of St. Augustine. They had a charism that had never yet been seen in the Church—that of the canonical life, which combined the life of a monk with that of a secular priest.

While maintaining the community life of a monastery, the Norbertines work extensively in the world, doing work like running parishes and schools. The term “canons” simply designates their attachment to a particular abbey or ecclesiastical body.

This combination of the monastic and secular religious life was very new in Norbert’s time—and was strong and sweet medicine for the Church, suffering as she was from a lack of holiness among her secular clergy.

The Norbertines preached, worked, combated corruption and heresy, all while maintaining the monastic heart of their order. They brought the sanctity of the monastery into a world hungering for holiness.

A second order of female religious and a third order for laymen (the first documented third order in the history of the Church) were founded in St. Norbert’s lifetime, their numbers growing exponentially with some of the noblest families in Europe seeking acceptance into their ranks.

Nine Centuries Later…

After an hour-and-a-half trip from Escondido, CA, a rented blue Tesla pulled into a parking spot outside St. Michael’s Norbertine Abbey in the peaceful canyon of Silverado. I stepped out of the piece of electric modernity into the present-day portion of the ancient and ongoing story of the Order of Premonstratensians.

The California sun filtered down, warming the golden walls of the church and monastery buildings of the Abbey. The buildings are new, but contain a deep sense of oldness with their beautiful architecture and monastic layout. The ancient roots of the community give the place a living sense of history, tradition, and continuing life.

The Abbey is embraced by rolling, scrub-tree-dotted hills. It’s easily accessible—about halfway between San Diego and Los Angeles and not far off a major highway—but has the distinctive feeling of something removed, peaceful, protected, and serene. It certainly seems more than a few miles away from the lanes of traffic and bustling lifestyle of Southern California’s metropolitan areas.

I—who can’t afford my own Tesla but thought it would be fun to pretend for a few days—was hardly the most distinguished guest the Abbey has ever welcomed. I was not a name like Dr. Jordan Peterson, who recently paid the Abbey a visit, but you would never have known it based on the reception I received. A smiling canon—Fr. Ambrose Criste—came to meet me and gave me as much of his time as I needed.

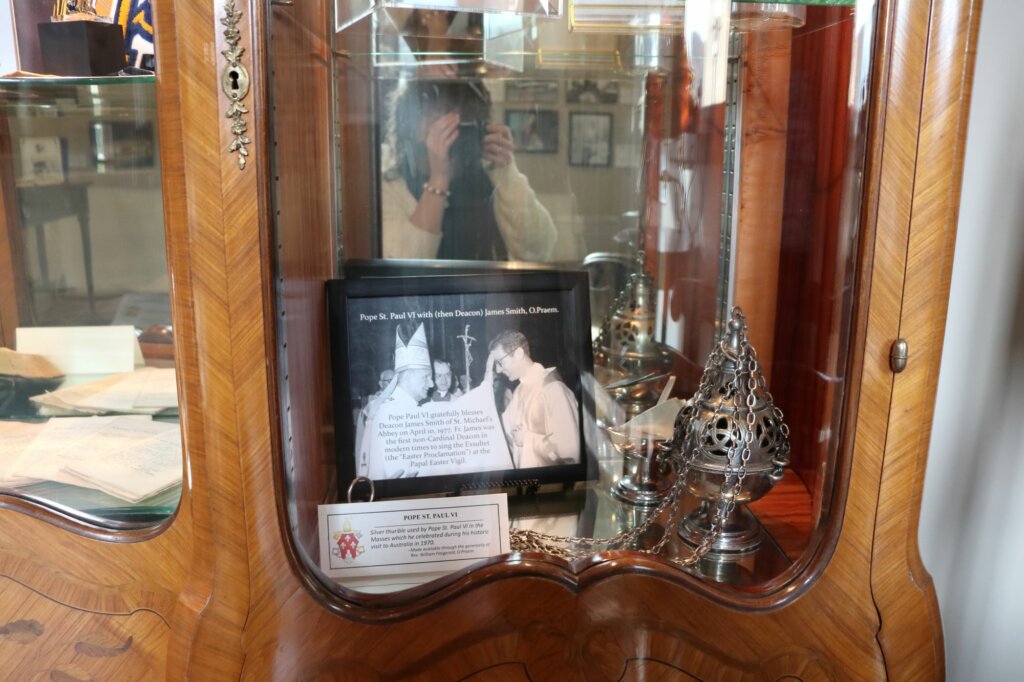

He spoke to me about the history of the Abbey (a captivating story of terror, faith, and survival with its origins behind the Iron Curtain), the work of the Norbertines in Southern California (and their extraordinary success despite the secular culture), and gave me a tour of their glorious abbey church—a stunning triumph of sacred art and architecture that forms the beating heart of this vibrant community.

Allow me to share some of what he told me.

Flee By Night—The Incredible Story of St. Michael’s Abbey

On July 11th, 1950, St. Michael’s Norbertine Abbey in Csorna, Hungary, received terrifying news.

Surrounded by the oppression of the Communist regime, the Norbertine Fathers were told that the authorities would arrive the next day to arrest them and shut down the ancient abbey, which dated from the first generation after St. Norbert.

What happens next reads like the plot of an Academy Award winner.

That very night, seven young canons in two groups fled the abbey with the blessing of their abbot, crossing the river and picking through dangerous minefields, carrying with them the mission to keep St. Michael’s Abbey alive in the free world.

(Historical sidenote: Interestingly, July 11th is a day of particular significance within the Norbertine Order. St. Norbert’s feast is generally kept on June 6th, but according to the older liturgical calendar, this date often fell within the octaves of Pentecost or Corpus Christi. A feast was instituted on July 11th so the solemnity could be kept with all due ceremony. I think that date has something to do with St. Norbert’s triumph over a peculiar heresy which consisted of some guy who convinced people to worship him and denigrated the Blessed Sacrament as nothing more than superstition. The defeat of such a man-centric, anti-God, anti-sacrament religion ties in appropriately to the fight against the secular forces of Communism.)

These seven canons hiked across Hungary to Austria, whence they made their way to America. Their story reminds me a lot of the Cistercians who fled Hungary at the same time and wound up as part of the founding faculty of my alma mater, the University of Dallas.

The Norbertines originally intended to return to Csorna, but as Communism tightened its grip across eastern Europe, it became clear that their path lay elsewhere. Though the monks of Csorna wouldn’t return to their abbey until 1990, the abbey survived, by the providence of God, and is populated today.

These Hungarian refugees first came to a Norbertine abbey in De Pere, Wisconsin, where they were welcomed after their harrowing journey. From there, the bishop of Los Angeles invited them to come run Catholic schools in his diocese, at a time when Catholic education was experiencing a huge boom across the country.

The Norbertines came, settling in Santa Ana in Orange County in 1961 and establishing St. Michael’s Abbey anew in their adopted country. They outgrew their initial location and, with tectonic instability precluding the possibility of expanding at the same location, chose a new one not far away in Silverado Canyon.

The new establishment (a total masterwork of traditional architecture and stunning sacred iconography) was dedicated just over two years ago on May 4th, 2021. They continue to experience exponential growth—now numbering about fifty priests and forty seminarians and currently establishing a new abbey in Springfield, Illinois.

Their work in California includes running two parishes in the area and a high school, as well as celebrating Mass, teaching, and preaching in other locales as well.

The Norbertine family expanded with the establishment of the cloistered Norbertine Canonesses around the year 2000, who live a few hours north and have experienced the same extraordinary growth, going from nine to fifty sisters in that time. And there is a community of active Norbertine sisters who work in the parishes!

Fr. Ambrose explained that their parishes and school are absolutely thriving, which fits the pattern of the places I have visited and written about in recent months: Catholic havens growing amid remarkably secular and un-Catholic environments.

Like those in Dublin, Warrington, and York, the Catholics in Southern California are drawn to this place, knowing they will receive the fullness of the Catholic faith here.

“A place like that,” said Fr. Ambrose, “where you have orthodoxy, orthodox Catholicism, reverent liturgy, and sound teaching and preaching becomes an absolute light on a hill in Southern California.”

In addition to their parish communities, the Abbey itself attracts a regular contingent of faithful who join the canons for daily Mass, prayer, and the Divine Office, and who take advantage of the hours and hours of confessions that the canons offer as a crucial part of their ministry.

If I didn’t live on the other side of the country, I’d certainly be one of the regulars.

Hic Domus Dei est, et Porta Caeli…

Terríbilis est locus iste: hic domus Dei est, et porta cæli: et vocábitur aula Dei.

Introit from the Mass for the Dedication of a Church

Terrible is this place: it is the house of God, and the gate of heaven; and shall be called the court of God.

My memory of St. Michael’s looms larger than the experience itself. Perhaps it’s the rosy tint applied by the seven months that have passed since, or maybe we find the real beauty of something after we’ve had time to think about it.

As Fr. Ambrose gave me a tour of Our Lady of the Assumption Abbey Church, someone with evident skill on the organ was practicing. The fast-paced, virtuosic bars of music boomed through the vaulted ceilings of the place, echoing amidst the many side chapels, the sanctuary with its monastic choir stalls lining the sides, and the nave that was more than large enough to accommodate hundreds of faithful.

(The organist’s practice session was captured forever on my iPhone’s voice memo that I was employing to record my conversation with Fr. Ambrose. It was fun to listen back to the recording.)

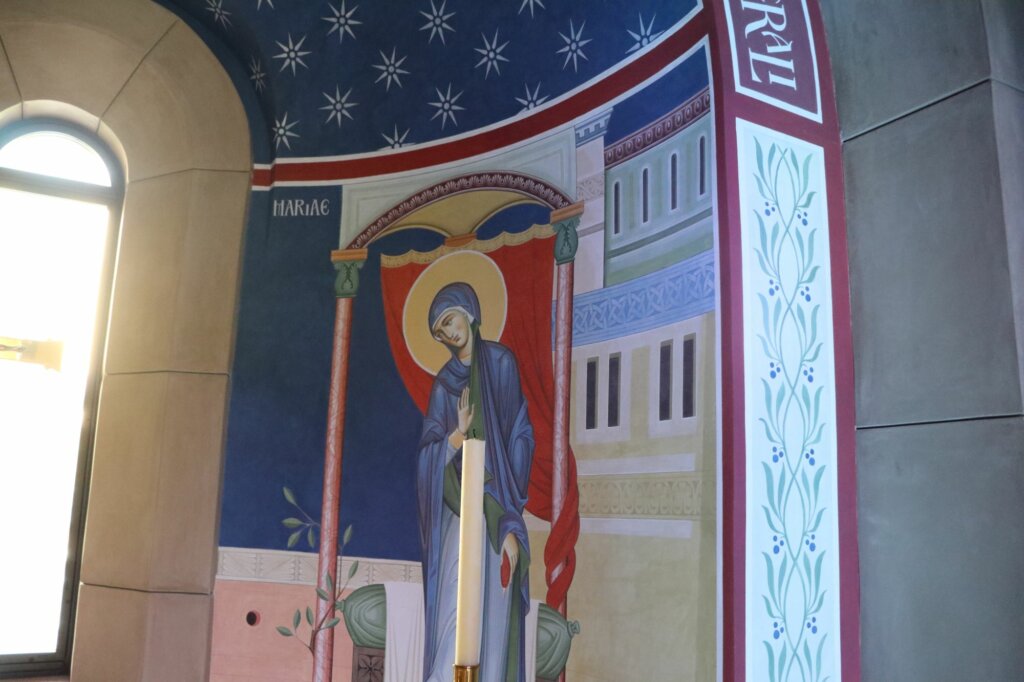

The church is adorned in the western iconographic style, all designed by Enzo Selvaggi—Creative Director for the sacred art studio Heritage Liturgical—and a team of Italian iconographers. In the apse (the recess behind the altar in the sanctuary) and the triumphal arch (section above the apse), these icons take the form of gorgeous mosaic—accomplished in nearly-unbelievable precision, beauty, and detail.

A jeweled cross, symbolic of Christ’s kingship, adorns the back of the apse and is surrounded by a continuous rainbow—the symbol of God’s fidelity to His promises. Vines emanate from the Cross, symbolizing the eternal life that grows from the Tree of the Cross and makes us one with the True Vine.

The triumphal arch is coated in shining gold and crowned by an image of Our Lady. She is surrounded by angels and the twelve stars described in the Book of Revelation. She receives a crown from her Son, Who is depicted as Christ Pantokrator—Christ in Majesty, the King of Heaven—at the apex of the arch. A deep blue portal, an entrance into heaven, opens up behind Our Lady, ready to receive her whom we call Porta Caeli, the Gate of Heaven.

The painted icons in the side chapels emanate life, light, and a unique warmth that isn’t always evident in eastern art. Fr. Ambrose explained that the eastern artistic traditions flowing through the hands of the Latin Rite artists who created these icons produces a singular effect—a combination of eastern symbolism and western human-ness, a warmth and glow that brings the icons to life and draws the viewer subconsciously into the scene. This fusion is the essence of the western iconographic tradition—a historical result of Greek elements arriving in the studios of Italian artists during the Renaissance, and those artists in turn learning from the Russian masters.

Fr. Ambrose also pointed out the imagery in the Annunciation Chapel to the left of the sanctuary. Each little detail in iconography has deep significance—there is nothing added simply for show or for fun.

Let’s explore:

- The red slippers that Gabriel wears indicate that he comes from heaven, as only members of the Byzantine imperial court wore red slippers.

- The ends of his head-tie, flowing behind him, are little “antenna” that indicate his continual “listening” for God’s message.

- The red thread that Our Lady is spinning symbolizes her motherhood of the Messiah. According to tradition, Our Lady spent her childhood working on the fine fabric for the temple veil, which was destined to be torn at the Crucifixion. At the Annunciation, she begins to weave in her womb the Divine Body that would be torn, bloody and red, on Good Friday.

Perhaps one of the most stunning elements of the church is also the simplest, and best appreciated on a sunny day—which is a frequent occurrence in Orange County. The windows that march along the top of the walls on either side of the nave are each tinted a different hue, and when the sun shines in, streams of rainbow light burst through the windows and fill the sacred space with vibrant, breathtaking color.

Defenseless Against Beauty

Truly this is the house of God, and the gate of heaven. Perhaps everyone, in words or in silence, has had similar thoughts as they’ve walked the hallowed halls of St. Michael’s. I’ve only touched on the various elements of the church briefly here. It would take ten blog articles to do it justice—and its ceiling isn’t even finished yet!

Truly, this is what a church should be: so overflowing with visual and audible beauty that it arrests us, almost forcefully quiets us, overwhelms us with its merciless onslaught of all that is lovely to look at and experience.

I heard an Irish Catholic artist once say:

We are defenseless against beauty. It breaks our heart.

Dony MacManus

Anyone who has had a memorable experience beholding something beautiful—such as a scene in nature or a piece of art or architecture—knows that beauty has a power that is utterly soul-piercing and masterfully bypasses any human “defense” against it.

That which is truly beautiful taps into a wire in our hearts that is connected to the divine, and when that wire is activated, the shock of it is more than startling.

Such an experience of beauty—while supremely wonderful—hurts. It elicits in us an unspeakable hunger. Even the most beautiful things on earth are but an evanescent glimpse of that eternal beauty that we know we cannot attain in this life, and that knowledge, though so often unconscious, is painful.

We are struck by beauty and left hungry and hurting, because we desire that beauty—or rather, the Source of that beauty—from the depths of our souls, and a mere taste is not enough.

We long for it, for that eternal Beauty—for God. We were made for God, and our destiny—if we choose to accept it—is to see Him at last in all His infinite beauty and perfection.

But what a long journey it is through this arid valley of tears before we reach our goal! How distressingly far it seems! How long, Lord, how long, cries the Psalmist:

As a hart longs

Psalm 42:1-3

for flowing streams,

so longs my soul

for thee, O God.

My soul thirsts for God,

for the living God.

When shall I come and behold

the face of God?

My tears have been my food

day and night,

while men say to me continually,

“Where is your God?”

This hunger and pain are, of course, of infinite purpose. They keep us fixed on God and upon our heavenly homeland. They fill us with the longing to behold beauty face-to-face, and strive to make ourselves worthy of it. Like Jacob who worked fourteen years to attain the beautiful Rachel, we will do whatever it takes.

Who knew that beauty was so much more than just a nice experience? Who knew that it could elevate our intentions, our minds, and our sense of purpose to such heights? That it is such a strong and convincing advertisement for heaven?

A Lived Beauty

In a place like a monastery, the experience of beauty is amplified because it is found within the context of a community whose members, like Jacob, are devoted to making themselves worthy of it. Beauty finds a natural home there, and effuses itself into every aspect of the monastery’s life.

We experience it in the reverent liturgies, beautiful icons, and harmonic music (and organ-playing) we find there. In the case of St. Michael’s, we see it in their particular devotion to liturgy and the sacred arts: the canons themselves practice the art of iconography and are masters of Gregorian chant.

We also perceive beauty in the rhythmic cycle of the Divine Office chanted seven times a day in this holy place; we see it lived in the celestial aspirations of an ancient rule, in a discipline of life and self that even a non-religious person would admire.

We know it in the generosity and charity that we receive as pilgrims and visitors.

We see it reflected in the joy that always seems to emanate from these places and the consecrated persons within them.

We recognize it in the selfless work these orders do—whether that be running parishes, teaching the young, caring for the sick, feeding the poor, or praying and sacrificing day in and day out for the good of the entire Church.

This is a living beauty, a lived beauty. A beauty we know is real. It’s a beauty that we know, somehow, exists by itself, beyond the individuals who are its human channels. It’s a beauty that we know, and want to be a part of.

It’s not a wonder we find ourselves so drawn to these places. They are heaven’s doors left ajar, so that we might see a little sliver of its eternal light.

Rise, Let Us Be On Our Way

I joined the canons for noon prayer when my visit was ending. The few minutes of simple chanted psalms, the gentle tones of the organ floating unobtrusively beneath it, were a fitting and uplifting send-off.

We don’t like leaving these stops where we have been given, unlooked for and undeserved, a little piece of our heavenly home. It takes effort to recommence our journey on the long road of life.

Even for the residents themselves, prayer ends and work begins. Contemplation is our destiny but can only be done in pieces, even at abbeys. For religious, there are confessions to hear, classes to teach, meals to cook, souls to counsel, gardens to tend.

For us wayfaring visitors, there is the active lay life to get back to, which is always in danger of being consumed by busyness and where it is so much easier to lose sight of our celestial goal.

But our friends who live so deeply in the other world teach us how to bring prayer into everything we do. The beauty we experience at these houses of heaven remains with us, helping us keep our gaze on heaven while our feet are on the earth.

Walk with your feet on earth, but in your heart be in heaven.

St. John Bosco

And so I, and everyone else who has had the great fortune of experiencing a little bit of life at a religious house, travel on…with gratitude and new energy for the road ahead.

Of course, we often leave with another consolation: the deep-seated feeling that we will be back. We are grateful for our brief time at St. Michael’s Abbey, and look forward to working with our newfound friends there in the near future. +

Have you ever visited a monastery or convent that has had a deep impact on you?

What did you love the most about it?

Tell us about it in the comment section below!

To experience more of the beautiful art, architecture, and music of St. Michael’s, visit their online digital library, The Abbot’s Circle.