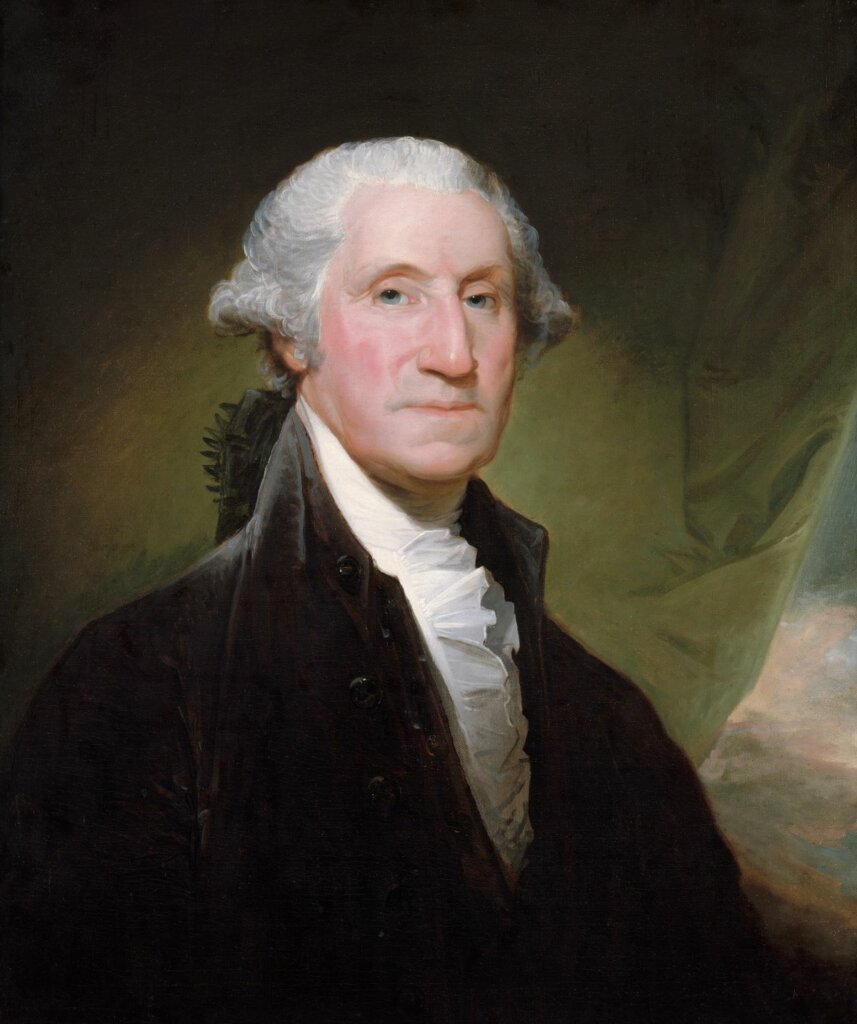

Was George Washington a Catholic?

Since the time of his death, it has been whispered that our first president, a lifelong member of the Church of England, had a deathbed conversion. Secular historians state that this is little more than wishful Catholic thinking, pointing out that there is no verified proof that such a momentous event ever took place. He was surely no Catholic, they say.

On the other end of the spectrum, this same view is held by many educated Catholics. Our Founding Father is well-documented as having been a Freemason and therefore part of the anti-Catholic Illuminati. Again, he was surely no Catholic!

But do these two perspectives, each accurate in some way, tell the whole story of Washington’s faith and his view of the Catholic Church?

George Washington and the Freemasons

By the time young Washington was in his teens, Freemasonry was the thing to do.

Boasting high ideals, advancement in social standing, plus the opportunity for praise and recognition, this exclusive society had much to offer colonial gentlemen.

Having lost his father at nine years of age, George never received the quality education abroad expected from a boy of his background. Despite coming from a well-to-do family, the Washingtons were still considered middle-class farmers. Whereas many of the other founding fathers were great scholars or accomplished writers, politicians, and philosophers, George was largely a self-taught, self-made man. It was something that he would be self-conscious about for the rest of his life.

He worked hard, attempting to fit in with his more academic peers. Freemasonry offered him the chance to rub shoulders with wealthy gentlemen, nobility even, and the opportunity to influence civil affairs through the philosophies of the Enlightenment era.

Still young and impressionable, nineteen-year-old Master Washington took his chance and joined the Masons. He was an active member for a few years until he joined the British military at the age of twenty-one.

Once in the militia, Washington’s dealings with the Masonic lodges grew more and more sparse. By his own testimony (in a letter to William Russell dated September 28th, 1798), from his enlistment to his presidency, he entered a lodge no more than two or three times, and only for funerals of fallen friends.

Perhaps the Masons had served their purpose now that he was climbing the ranks and finding honor; perhaps he found something about the secret society distasteful. In any event, he would not deal with the Freemasons again until after the war with Great Britain, when he had become a national figure. At this point, when his accomplishments were well-known and he was on the verge of the presidency, he was flooded with attention from the Freemasons. Honors and titles were bestowed upon him but, again, not because he was an active participant, but more so because he was famous.

While he never completely severed ties with the organization, Washington seems to have kept Freemasonry at arm’s length during his years of renown, with only the occasional attendance at a public ceremony given in his honor or an even rarer visit to a Masonic lodge when his presence was specifically requested. Subsequently, the honors and titles showered upon him were largely honorary or ceremonial; some of these, even, he refused to accept.

Washington’s burial was well-remembered for exhibiting Masonic funeral ceremony rites: a statement that he was one of their worthy brethren. Yet these were not his final wishes, as he had hoped instead to be buried simply and quietly with little pomp and many prayers.

Washington’s Catholic Friends

Washington’s contributions to the Freemasons in the latter half of his life appear limited to a few charities and even in these, America’s first Commander-in-Chief gave more generously to Catholic institutions—a strange choice for one who was supposedly anti-Catholic.

In fact, George Washington may have offered more assistance to the Church in the colonies than any other public figure of that period.

During the Revolutionary War, General Washington appears to have been struck by the contributions of Catholics in support of the American cause. Having, for the most part, been colonized by Protestants (many of whom were Anglicans and Puritans), the New World was mired in an anti-Catholic mentality. Papists were forbidden to vote, practice law, or hold office, all while being subjected to heavy fines and restrictions for worshiping in public.

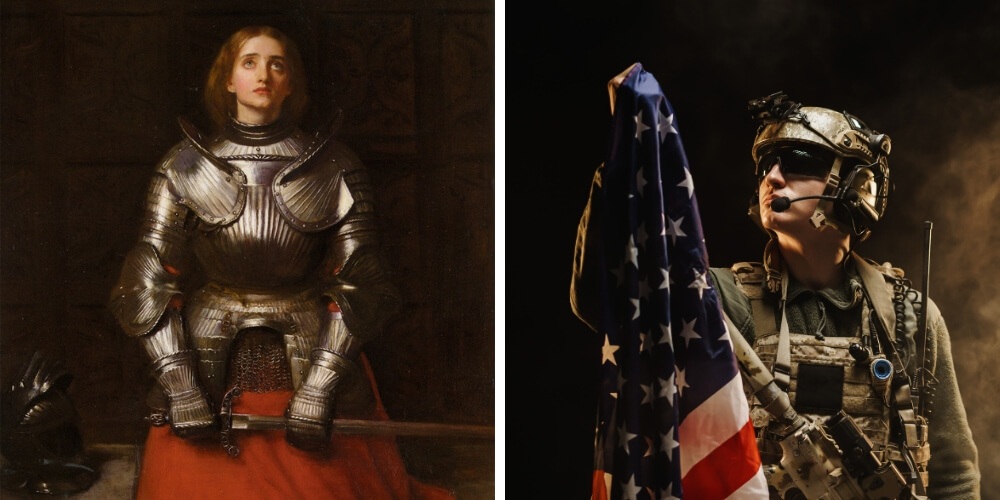

Yet when the war broke out, Catholics were on the front lines of the cause for liberty. Several of the officers and numerous soldiers who served under General Washington were members of the Church of Rome, notably:

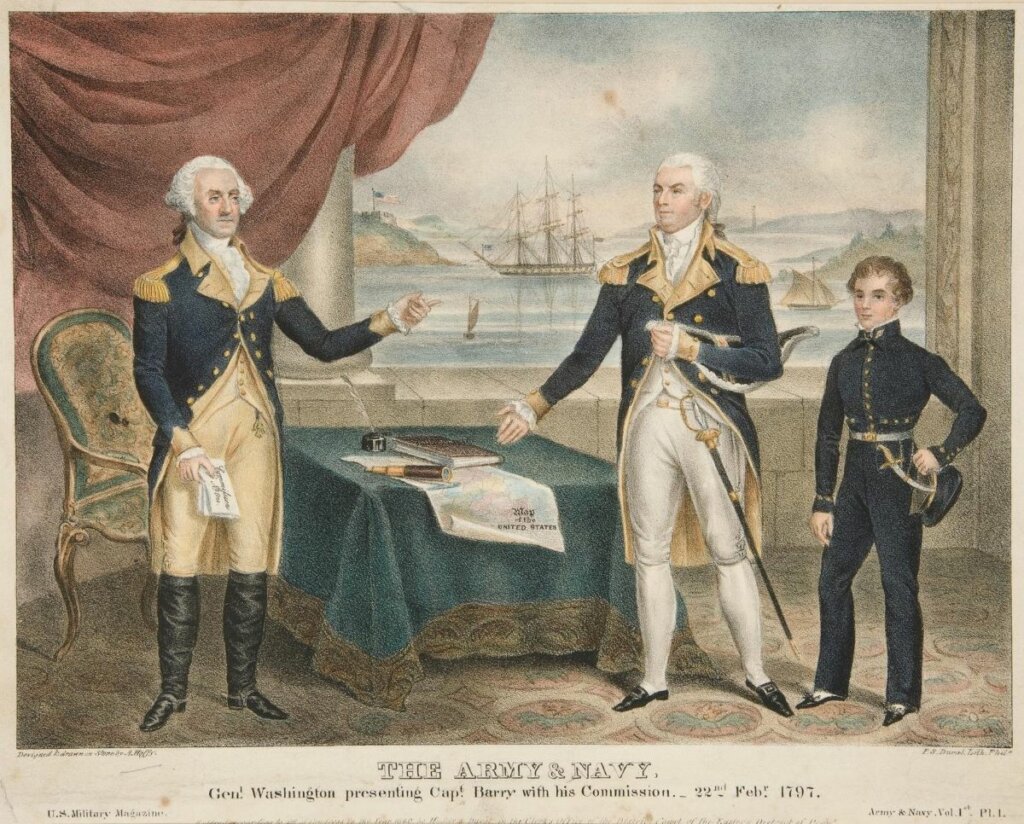

- Commodore John Barry, appointed by Washington as an officer in the U.S. Navy;

- Captain John Fitzgerald, one of his aides-de-camp

- The French commander Marquis de Lafayette, whom Washington held in highest esteem

The Commander-in-Chief also banned any public celebrations of Guy Fawkes Night, where effigies of the alleged author of the infamous gunpowder plot were burned, along with other Catholic figures, such as the pope.

As the Commander in Chief has been apprized of a design form’d for the observance of that ridiculous and childish custom of burning the Effigy of the pope – He cannot help expressing his surprise that there should be Officers and Soldiers in this army so void of common sense, as not to see the impropriety of such a step at this Juncture; at a Time when we are soliciting, and have really obtain’d, the friendship and alliance of the people of Canada, whom we ought to consider as Brethren embarked in the same Cause. The defence of the general Liberty of America: At such a juncture, and in such Circumstances, to be insulting their Religion, is so monstrous, as not to be suffered or excused; indeed instead of offering the most remote insult, it is our duty to address public thanks to these our Brethren, as to them we are so much indebted for every late happy Success over the common Enemy in Canada.

George Washington, Order in Quarters, November 5th, 1775

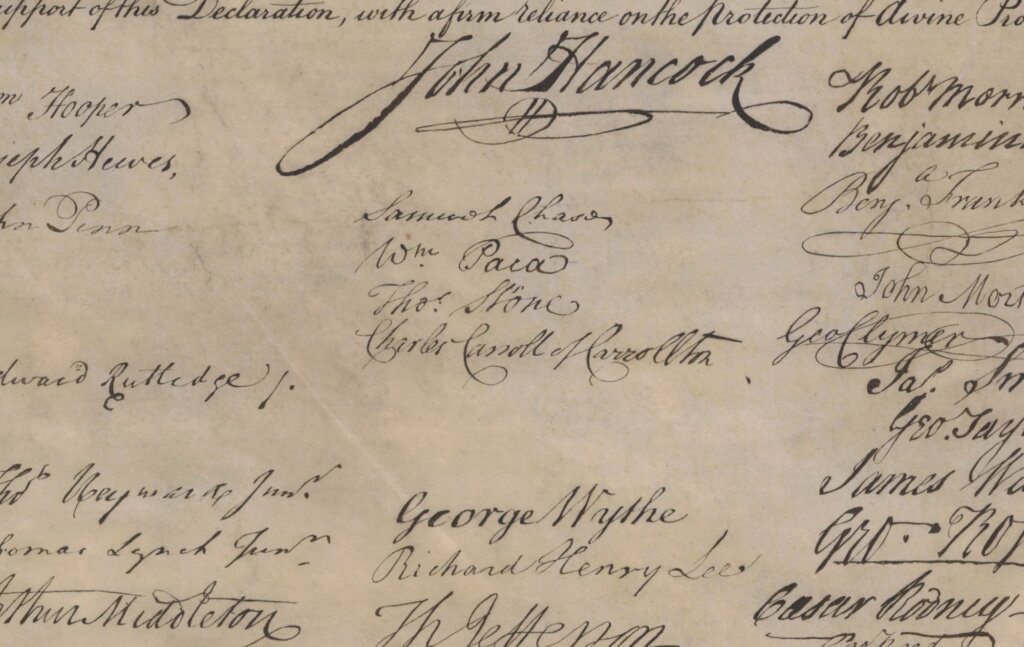

Washington also would have recognized the immense sacrifices undertaken by one of America’s forgotten founders: Charles Carroll of Carrollton.

Considered to be possibly the wealthiest man in the colonies, Charles had more to lose than most who fought for freedom. Credited with single-handedly financing the Americans, Charles was the only Catholic member of the Continental Congress to sign the Declaration of Independence. Later, he would serve on the board of war, where he supported Washington through thick and thin. A great respect grew between the two men and, eventually, their mutual respect grew into friendship.

The same year that Washington was unanimously elected president of our new country, Fr. John Carroll, cousin of Charles, was also appointed its first bishop. Here, too, admiration sprang up between the two leaders.

Congratulating Washington on his election, the bishop sent the new president a letter on behalf of the Catholics of the nation, expressing his wish for Catholic toleration:

While our country preserves her freedom and independence, we shall have a well-founded title to claim her justice, and the equal rights of citizenship, as the price of our blood spilt under your eyes, and to our common exertions for her defense – rights tendered more dear to us by the remembrances of former hardships.

Washington responded, graciously thanking Bishop Carroll for his well-wishes and for the numerous examples of courage and honor set by Catholics during the nation’s extraordinary struggles:

I presume that your fellow citizens will not forget the patriotic part which you took in the accomplishment of their Revolution, and the establishment of their government or the important assistance which they received from a nation in which the Roman Catholic faith is professed.

Furthermore, he expressed his wish that Catholics be treated as first-class citizens and be “equally entitled to the protection of civil government.”

The president did not stop at words, but would make good this desire in his deeds.

Washington’s Catholic Deeds

Washington was known to visit several houses of worship, even if they were not Anglican.

He was also known to have attended Holy Mass on occasion and, while the American Constitution was being drafted in Philadelphia during the Constitutional Convention, George made a point to lead all the delegates to Mass being celebrated nearby at St. Mary’s Catholic Church. This sent a message to the political representatives of the nation: Catholics were to be treated with the same respect as all other citizens.

President Washington even went so far as to support the building of Catholic churches in Philadelphia, Virginia, and Baltimore. His financial donations to these endeavors are said to have exceeded even the Carrolls’.

In his personal life too, the American patriot seems to have adopted some Catholic elements. His personal aide and manservant, Juba, as well as Lieutenants Stephen Moylan and John Fitzgerald all report that he always made the Sign of the Cross before meals and prayer—an exclusively Catholic custom.

More interesting still is the painting of the Blessed Virgin Mary he displayed at his residence in Mount Vernon. Out of the hundreds of paintings that he owned, this was only one of two religious images, but it appears to have had a place of honor in his abode.

One or two instances of an Anglican Freemason showing tolerance to Catholics would have been possible but unusual; numerous gestures of public support, however, were simply unheard of.

But what of Washington’s supposed conversion? Does anything of substance indicate that he did, in fact, embrace the Faith?

Examining the Evidence

On February 24th, 1957, the Denver Register published a brief account of the incident:

It was a long tradition among both the Maryland Province Jesuit Fathers and the Negro slaves of the Washington plantation and those of the surrounding area that the first President died a Catholic…The story is that Father Leonard Neale, S.J., was called to Mount Vernon from St. Mary’s Mission across the Piscatawney River four hours before Washington’s death.

The American Catholic Historical Researches, 1900 by Martin Griffin sheds even more light on this episode:

The night before Washington died, during a fierce storm, his colored body servant came riding down to the bank of the Potomac and after being ferried across said he had come in search of a Catholic priest. After some delay, one of the old Jesuit Fathers from the mission on the Maryland side was found, taken over the river to Mount Vernon, where he went at once to Mr. Washington’s room and remained there with him three hours. When he left he seemed much gratified and said to those about him that there need be no more apprehension for Mr. Washington as the future of his soul was secure. He was then taken back to the Maryland shore and old darkeys tell with unvarying detail that their fathers believed Washington died a Catholic…

In addition the Jesuit record says that on the day after the visit to Mount Vernon the old Jesuit went to the Superior of the mission and relating the fact of his journey, handed the Superior a sealed packet saying I am not permitted to detail what transpired between Mr. Washington and myself in his room at Mount Vernon but I have written it out carefully here and after we both have passed away and occasion requires this can be opened and its contents made public. The Superior took the paper and placed it among the records of the mission where it remained until shortly after the death of the old Jesuit when it was boxed up still unopened with a lot of other papers, and sent to headquarters of the Order in Rome where it is still supposed to be awaiting the fortunate chance that will disclose it to the hand of some appreciative investigator who may throw some light on this very curious historical question.

Skeptics have long since decried these accounts as fictitious. Historians in particular point to Tobias Lear, Washington’s personal secretary, who was present at his death. Lear’s written account detailing the passing of the father of our country gives no indication of a visiting priest, let alone a final conversion. If a Jesuit priest did indeed visit Mount Vernon that night, why would his personal secretary fail to make official note of it? Again, it is asserted that he was no Catholic!

Yet Lear makes no mention either of the old general’s last conversation with his wife, Martha, who remained with him in his parting moments.

Furthermore, despite Washington’s admirable efforts, much of the United States still clung to anti-Catholic bias. At that time, it was not only frowned upon, but considered borderline scandalous for a Protestant to become a Catholic, especially in high society. Had this actually occurred, it seems no great stretch to imagine that Washington’s household and colleagues would have intentionally omitted any details that might have tarnished his reputation among the Protestant elites.

In any case, Washington’s slaves, most of whom he freed upon his death, held the belief that, in the end, George died a Catholic:

The long report among slaves of Mount Vernon as to Washington’s deathbed conversion would be odd unless based on truth. These were not Catholic Negroes; it is part of the tradition that weeping and wailing occurred in the quarters that [Washington] had been snared by the Scarlet Woman of Rome, whom they had been taught to fear and hate.

Denver Register, May 11th, 1952

Whether he lived his life as an Anglican, Freemason, or simply a Deist, the hope that Washington turned to the one, true Faith at the conclusion of his earthly sojourn is a very real and persistent one.

Beloved by Americans, Bishops, and Popes

In the aftermath of his passing, the entire country was plunged into mourning for the beloved Father of America. Eulogies, tributes, and funeral orations were offered from every walk of life, honoring this larger-than-life figure.

Catholics too showed no stinginess when it came to praising him.

His friend, Bishop John Carroll, stated his boundless admiration for the man in the first of two official eulogies:

Whilst he lived, we seemed to stand on loftier ground, for breathing the same air, inhabiting the same country, and enjoying the same constitution and laws, as the sublime, magnanimous Washington.

In his second tribute, Carroll related that his fellow countrymen had no greater friend here on earth than Washington. He was, as the bishop pointed out, proof that God loves us. Divine Providence may be the true Father of our country, he said, but Washington was the perfect instrument with which God showered abundant blessings upon this Constitutional Republic. If we were to follow his worthy example, Our Creator would surely continue to bless us, and our country would continue to grow and thrive.

Remarkably, praise for Washington came not only from the bishop of America, but from subsequent Bishops of Rome as well.

Pope Leo XIII in his encyclical Longinqua offered the following in 1895:

Precisely at the epoch when the American colonies, having, with Catholic aid, achieved liberty and independence, coalesced into a constitutional Republic the ecclesiastical hierarchy was happily established amongst you; and at the very time when the popular suffrage placed the great Washington at the helm of the Republic, the first bishop was set by apostolic authority over the American Church. The well-known friendship and familiar intercourse which subsisted between these two men seems to be an evidence that the United States ought to be conjoined in concord and amity with the Catholic Church.

Years later, in 1939, Pope Pius XII said in his encyclical Sertum Laetitiae:

When Pope Pius VI gave you your first Bishop in the person of the American John Carroll and set him over the See of Baltimore, small and of slight importance was the Catholic population of your land. At that time, too, the condition of the United States was so perilous that its structure and its very political unity were threatened by grave crisis. Because of the long and exhausting war the public treasury was burdened with debt, industry languished and the citizenry wearied by misfortunes was split into contending parties. This ruinous and critical state of affairs was put aright by the celebrated George Washington, famed for his courage and keen intelligence. He was a close friend of the Bishop of Baltimore. Thus the Father of His Country and the pioneer pastor of the Church in that land so dear to Us, bound together by the ties of friendship and clasping, so to speak, each the other’s hand, form a picture for their descendants, a lesson to all future generations, and a proof that reverence for the Faith of Christ is a holy and established principle of the American people, seeing that it is the foundation of morality and decency, consequently the source of prosperity and progress.

These accounts offer a compelling description of the American Cincinnatus but, fascinating as they are, they offer little hard proof that Washington was ever actually baptized. However, they should not be ignored either, for they serve as a reminder that whether or not this great man accepted the fullness of Christianity, the hope of salvation belongs to all—even a president.

George Washington’s life was an exceptional one, but especially so in the pious manner in which he remained open to truth. Here was a man who, during the better part of his life, was not an official member of the Faith, but who did more to promulgate, cultivate, and facilitate its flourishing in our country than many who called themselves Catholic.

At worst, he was an admirer and ally of the Church in a land where she had only a precious few friends; at best, he may be an uncanonized saint. Either way, his life story is surely an inspiring one.

And who knows? Perhaps the tangible proof of George Washington’s conversion is still waiting to be revealed. If the account of Fr. Neale happened as it was told, then the truth of that night may lie inside a sealed package hidden beneath the streets of Rome, deep within the vaults of the Vatican Secret Archives.