“Dragon-slayer,” “Victory-bearer,” and “The Great Martyr” are just a few of the many illustrious titles given to one extraordinary man: St. George. April 23rd is his glorious feast and it is a day overflowing with accounts to enliven faith, ignite courage, and inspire wonder.

Precious little has been verified historically about this champion of God, and yet he is remembered and singularly beloved all over the world.

What we do know is that he was raised in what is now Turkey and brought up in the Christian Faith by his Greek parents. He became a high ranking soldier of Rome during the reign of the Emperor Diocletian and gave up his position of power by declaring himself a Christian. He was beheaded, winning the crown of martyrdom around 303 A.D.

It is a simple but powerful tale of bravery, self-sacrifice, and nobility.

Understandably, the early Christians lost no time in sharing this story of heroism, ensuring that all would remember his name. Constantine I assumed power just a few short years later and immediately cultivated devotion to the soldier-saint by building over twenty churches dedicated to him. Veneration spread quickly and dozens of countries appointed the saint as chief patron of their lands.

It is not difficult to pick up on the enthusiasm with which his cult spread if we look at the ever-impressive, widely-circulated accounts of his life. These narratives, doubtless based on true testimonies, were soon transformed into incredulous yarns full of miraculous and marvelous works.

Today, almost nothing remains of his original story that is authentic, or even believable, but whether or not the legends are valid, the reverence with which the Christian faithful admire this heavenly hero speaks louder than epic tales ever could.

But why do we celebrate the life of this Roman officer and how has his reputation survived for so long? While St. George proved to be a prominent patron fairly quickly in the Eastern world, it would take a little more time for the West to match that enthusiasm.

But match it they did.

By the Middle Ages, the cult of St. George had exploded in popularity. Most appropriately, devotion to the great warrior was spread through those who had adopted the same profession: soldiers, specifically the soldiers of the Crusades.

Signed with the Cross: St. George and the Crusades

As the Islamic faith spread, the Muslims swept across Christendom in their conquest of Europe. Christians under their rule were often persecuted or killed.

In 1095, Alexios Komnenos, emperor of the Byzantine empire, requested that Pope Urban II organize an army to stop the invaders and recover the cities in the Holy Land that Islamic forces had taken over. Pope Urban urged the faithful with the following plea:

“Your brethren who live in the east are in urgent need of your help, and you must hasten to give them the aid which has often been promised them. For, as the most of you have heard, the Turks and Arabs have attacked them and have conquered the territory of Romania [the Greek empire] as far west as the shore of the Mediterranean and the Hellespont, which is called the Arm of St. George. They have occupied more and more of the lands of those Christians, and have overcome them in seven battles. They have killed and captured many, and have destroyed the churches and devastated the empire. If you permit them to continue thus for awhile with impunity, the faithful of God will be much more widely attacked by them.”

Much of Christendom responded and the newly-formed armies became known as the “Crusaders.” The term “crusade” refers to “one who is signed with the cross,” or more loosely, “one who journeys along the way of the cross.” To be a “crusader” was a strong testament of bravery and, more importantly, of faith.

St. George Works a Miracle at Antioch

An early campaign of the First Crusade was the Battle of Antioch, a city essential for retaking Jerusalem.

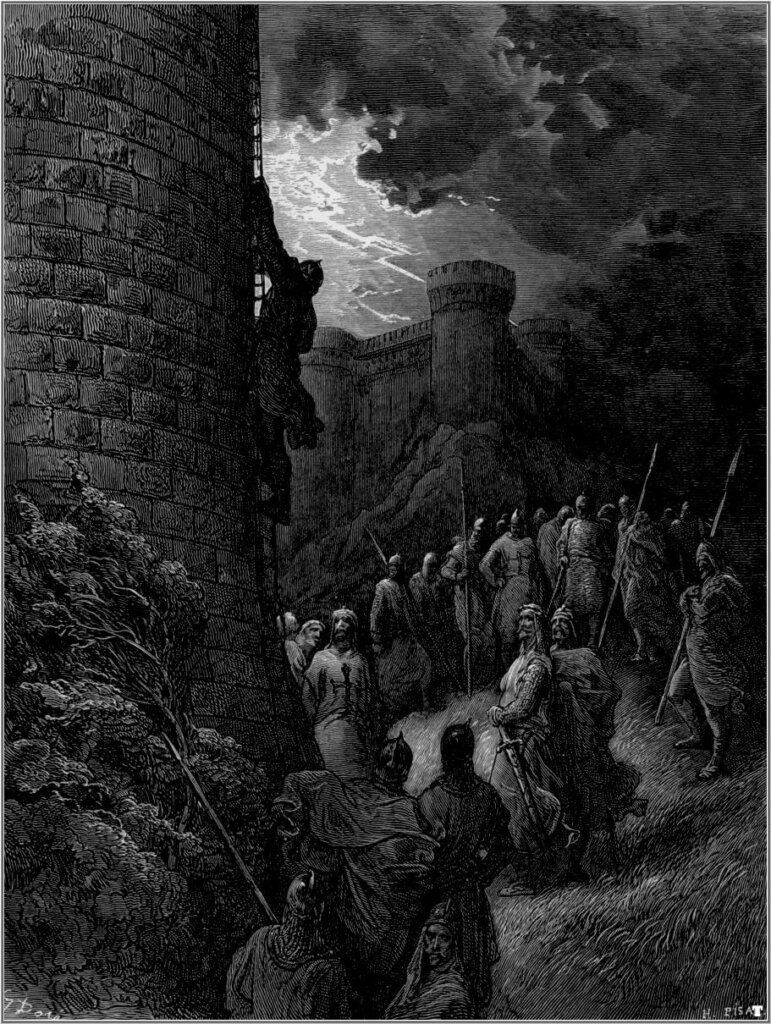

In the autumn of 1097, the Crusaders began a nine-month siege. It was a period of intense hardship. Antioch’s battlements, capable of withstanding all the armies in the world, were too immense for a full-on assault. Instead, the knights of the Cross would have to play a waiting game and hope to starve the city out; a painfully slow process.

In the meantime the Turks within were determined to make the Crusaders’ lives as difficult as possible through numerous raids, sorties, and skirmishes along the towering walls. Mild autumn was replaced by harsh winter and with it came new hardships for both sides: food shortages, unpredictable weather, and debilitating disease. The Crusaders suffered losses from war wounds, illness, and desertions, and still there appeared to be no definitive end to the struggle.

With the arrival of spring, news came of an army on the move; Islam was sending new troops to annihilate the Christian forces in their encampment and would arrive within weeks.

In a desperate move, a secret deal was struck between a defecting gatekeeper of the city and a Frankish noble, which finally permitted the Crusaders access into the city. After a brief battle, the city was taken and the Christians were victorious.

But the fight was not over. The new Muslim army was within sight of the city even then and soon the besiegers were besieged.

Knowing that no help could come and that they would not survive within the beaten and already starved city, the Crusaders resolved to fight to the last.

One month later, on June 28th, 1098, the remaining forces emerged from the gates and valiantly charged into the attacking Islamic armies. The battle was fierce, but it seemed that the bravery of the Christian soldiers would not be enough to win the day.

It was then that something extraordinary occurred.

The medieval historian and monk Matthew Paris of St. Alban’s Abbey describes the event:

As victory swung uncertainly from one side to the other, an invincible army was seen coming down from the mountains, its warriors seated upon white horses and carrying dazzling white flags before them. Then from the emblems on the flags they knew that the army was advancing behind St. George, St. Demetrius and St. Mercurius.

Nearly every major chronicler from the First Crusade records something of this sudden and unforeseen help from heaven and, while the identities of his hallowed companions sometimes differ between the authors, all agree that on that day the Crusades were saved by St. George himself.

The Turks were put to flight and those who remained were quickly vanquished. Christendom was victorious and the road to Jerusalem lay open and free.

A year later, on June 7th, 1099, the crusading army reached the outskirts of the Holy City. Again they laid siege and once again it is said that the champion of Christ assisted them in their hour of need. The Golden Legend states:

…when the Christian hosts were about to lay siege to Jerusalem, a passing fair young man appeared to a priest. He told him that he was St. George, the captain of the Christian armies; and that if the Crusaders carried his relics to Jerusalem, he would be with them. And when the Crusaders, during the siege of Jerusalem, feared to scale the walls because of the Saracens who were mounted thereon, Saint George appeared to them, accoutred in white armour adorned with the red cross. He signed to them to follow him without fear in the assault of the walls: and they, encouraged by his leadership, repulsed the Saracens and took the city.

England—Land of the Red Cross

Although intermittently used as a small badge of the crusading fighters, the red cross mentioned here was not previously associated with this wonderworking warrior. After the Holy Land was reclaimed, however, the fiery cross was emblazoned on the standards of armies throughout Europe and soon it became the universal symbol of Christian knighthood. Consequently, the Crusaders would not only be “signed with the Cross” of faith, but also with the scarlet cross of their newfound hero—the Cross of St. George.

While this insignia was incorporated by many men of various ranks and nations, Richard I of England is most famously credited with his use of it. As notably featured in the legends of Robin Hood, Richard the Lion-Hearted publicly adopted the red cross as the official symbol of the English kingdom and placed himself and his men under the protection of the holy George.

During the First Crusade, the Muslims had destroyed the church of St. George in Lydda after their flight from Jerusalem. (It is in Lydda that the remains of the saintly soldier are believed to rest.) One hundred years later, around 1191, during the Third Crusade, King Richard took it upon himself to restore the ruined shrine in remembrance of the captain of his armies.

Once the war was over, the veterans no doubt brought many of the new military devotions back home with them—and they were spread with as much relish and artistic license as ever! In fact, it was around this time that the famous incident with the dragon emerged.

The monster presented an adequate foe for the guardian of the Church, as it suitably personified the persecuting power of paganism or the snares of Satan. By vanquishing the brute and rescuing the princess and her village from its ferocious fangs, St. George stood as a bulwark of the Church, protector of the weak, and an honorable mediator on behalf of the faithful.

A glorious Christian martyrdom, the war stories of the Crusaders, tales of ghostly armies from heaven, a battle with a dragon—all these stories revolve around this one remarkable and mysterious champion.

In fact, the pious legends left such an impression upon the English that, in 1327, King Edward III made St. George the official patron of England and founded the Order of the Garter, the nation’s oldest and greatest order of knighthood, under George’s patronage. April 23rd was (and still is) celebrated as a public holiday and was a Holy Day of Obligation for Catholics from 1415-1778.

The Sun Never Sets on St. George

As the English kingdom grew and expanded, so did the legends of St. George. It was once said that the sun never set on the British Empire, so vast was its territory; thus, wherever the English identity was established (even here in America), the stories of the red cross knight were not far behind. To this day, the saint’s influence can be easily spotted in the flag of England, where the Cross of St. George remains as the sole feature.

It is little wonder then that the Eastern Church speaks of him in reverence and awe as The Megalomartyr, a title given to the greatest of all who shed their blood for Our Lord. The Roman Catholic Church in the West has spread his devotion with equal enthusiasm and honors him as the epitome of saintly valor. Protestant denominations, too, place particular importance on his patronage.

Remarkably, Muslims also honor Al-Khidir, the Evergreen Servant of God, as the only Christian saint worthy to be mentioned in the Quran. There are even those of the Jewish faith who will admit that St. George is an admirable figure.

Therefore, it is a remarkable thing indeed that this faithful friend of God could have such a lasting effect on our history and yet remain veiled in near obscurity, as we know so little, in fact, about the holy man himself. And yet, few can rival his unmistakable qualities: his courage in the face of adversity, his self-sacrifice in the service of the innocent, and his unshakable determination that deadly dragons must be slain.

Here is a soul worth remembering. Here is a saint to celebrate. St. George, pray for us!

Want to find out more about how our great saints can lead you to a more heroic life? Check out our series Heroic Virtue.